Fog Of Information War: Army Asks Civilians, Allies For Aid

Posted on

A soldier from the Army’s offensive cyber brigade during an exercise at Fort Lewis, Washington.

WASHINGTON: From fake-news trolls subverting US elections to deniable drones blowing up Saudi oil facilities, America’s adversaries have found new ways to strike without giving the Pentagon a clear target to strike back at. That’s why the increasingly anxious armed forces are wrestling with so-called grey zone operations and information warfare. But a successful response requires far more than the military, the Army’s three-star senior futurist says. It will take a unified effort with civilian agencies and foreign allies.

US law and culture make that extremely difficult to do, Lt. Gen. Eric Wesley acknowledged. But it’s a challenge the Army can’t simply set aside, he said. Letting adversaries muddy the debate can dramatically affect whether and how the military will be employed.

After drones and missiles temporarily slashed Saudi oil production in half, which Secretary of State Pompeo immediately blamed on Iran, it took President Trump three days to publicly state “it’s looking that way” but the evidence was still “being checked.” It took nine days for Britain, France, and Germany, all vital US allies, to officially and publicly blame Tehran.

Lt. Gen. Eric Wesley talks to a fellow soldier at an AUSA conference on artificial intelligence.

Some of this delay is due to the peculiar processes of the Trump Administration and widespread distrust of the administration abroad. But the enthusiastically multilateralist Obama Administration suffered a similar crisis of uncertainty back in 2014, when Russia invaded Ukraine with “Little Green Men” bearing no identifying insignia on their uniforms. By the time the US and NATO all publicly agreed the commandos in Crimea were indeed Russian soldiers, the territory was firmly under Moscow’s control.

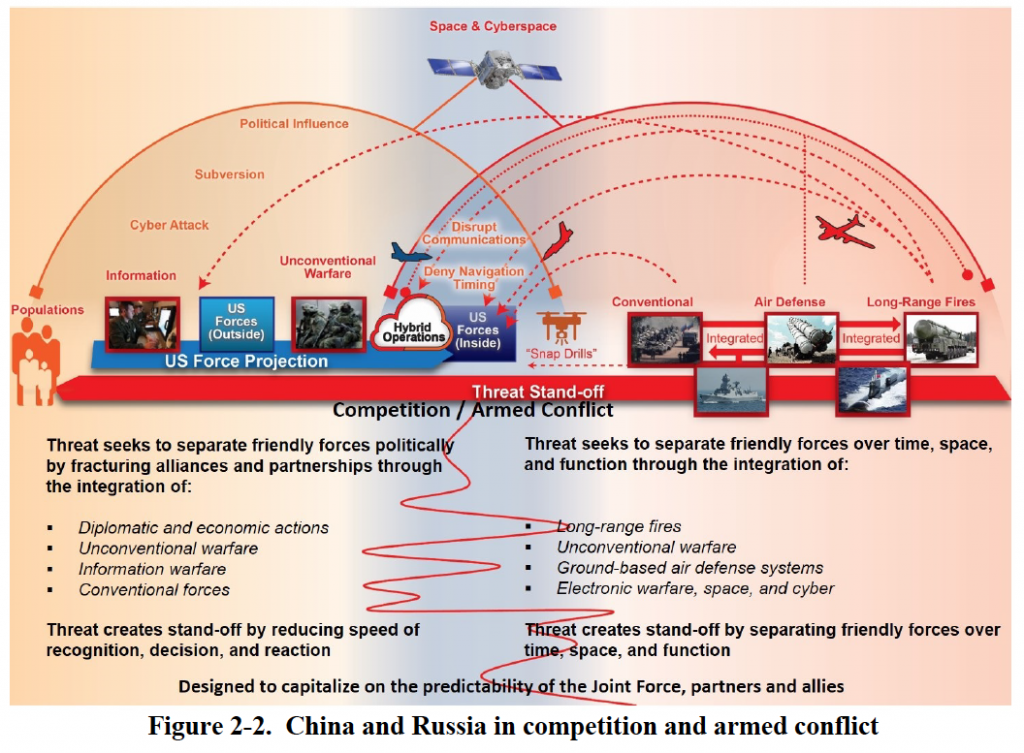

Governments and militaries have always wrestled with the fog of war. But ironically, the information age can make that fog much thicker and easier to generate. Clever use of unmanned weapons, online disinformation, and deepfake videos can confuse decisionmakers — especially in democracies — into delaying a response.

If an adversary can confuse and delay the West while it seizes objectives, deploys its defenses, and digs in — what Wesley calls “a fait accompli attack” — it would take a costly combat operation to kick them back out. “If you can deter that effort, even if it gets ugly once in a while,” he said, “[that’s] far better than if you’re mobilizing from the continental United States… to engage in protracted conflict.”

But acting promptly requires getting clarity on what’s actually happening. How?

Latvian soldiers train with US Airborne troops.

Fighting Through The Fog

Deliberately creating “ambiguity in the battlefield” is a powerful way to keep the West from acting in time, Wesley told a Center for European Policy Analysis conference on Monday. In military terms, it’s another form of “stand-off,” similar to anti-aircraft missiles or naval mines, because it, too, can keep the US military from bringing its might to bear.

The countermeasure, he said, is constant, coordinated effort — not just by the US military and its growing information warfare forces, but by civilian agencies and foreign partners.

US troops in in Vietnam

That’s something the US has historically not done well, Wesley acknowledged.

“One of the reasons we struggle with it is we see it as an afterthought,” he told the CEPA conference. “We do it episodically, anecdotally.”

Instead, “we have to continually be countering information warfare and unconventional warfare,” Wesley said. That requires day-to-day coordination among the US military, US civilian agencies, and allies, he said, through “operational headquarters that are conducting competition every single day in an aggressive and rapid manner.”

But what does that look like in practice, I asked Wesley the next morning, when he made a second DC appearance at the Brookings Institution. One good analogy, he said, is the kind of “war room” used by US political campaigns since the Clinton era “to watch the news cycle every single day and appropriately counter it.”

This can’t be done agency-by-agency or even country-by-country, Wesley said. “We allow, for understandable reason, the country teams of each of our embassies to lead on messaging for any given country,” he said — but the information age allows disinformation and agitation to spill swiftly across borders. That requires a higher level of coordination.

Who’s supposed to make that happen? The State Department has no equivalent of the military’s four-star regional combatant commanders, I pointed out.

The military’s geographical Combatant Commands (COCOMs).

“No, but they do have regional ambassadors, and that could be something that we are able to increasingly collaborate on,” Wesley said. (He’s presumably referring to the heads of the State Department’s regional bureaus for Africa, East Asia, Europe, the Near East, South Asia, and the Western Hemisphere, who are usually, though not always, career foreign service officers of ambassadorial rank).

So is the Army proposing new interagency structures, asked Brookings moderator Michael O’Hanlon, or embedding interagency liaisons in regional Combatant Command HQs?

“We haven’t proposed structural change to the government. That wouldn’t be our role,” Wesley said, “but we have described what it takes to win: [being] actively engaged…on a daily basis [with] a coherent command and control mechanism … that organizes those messages.”

Of course, command and control is a distinctly military concept that’s profoundly alien to the State Department and other civilian agencies. Interagency collaboration tends to lurch and halt, slowly and painfully, through protracted consensus-building rather than decisive top-down leadership. Even if the civilian agencies act decisively, they have only a tiny fraction of the military’s resources to act with.

SOURCE: Army Multi-Domain Operations Concept, December 2018.

A Concept Too Far?

“This call for more interagency involvement has been a constant for 30 years…in Iraq, in Afghanistan, and even in the Gulf War in ’91 before that, the Balkans,” Tom Spoehr, head of defense studies at the Heritage Foundation told me after Wesley’s remarks. The civilian agencies have never had the funding, manpower, or organization to meet the military’s demands.

Spoehr firmly believes the Army should retain its hard-won experience in counterinsurgency and continue creating dedicated units of advisors, which he thinks can play a valuable role against Russian and Chinese proxy forces. But he’s skeptical the Army should let itself be pulled into other aspects of the grey zone.

Thomas Spoehr

The US did have a sizable civilian “messaging” effort during the Cold War, but it largely dismantled it in the 1990s. “This ability to compete in information warfare …. the United States has not had that for decades,” said Spoehr. “I see no movement in town to regenerate that capability. The Army shouldn’t dwell on that because it’s something we can’t affect.”

Spoehr’s not the only skeptic. When Wesley and his staff were drafting what became the Army’s official concept for Multi-Domain Operations, they not only covered the “conflict phase” — open warfare between nation states — but also heavily emphasized the “competition phase” — the grey zone of information and proxy warfare short of open conflict. That emphasis fit perfectly with then-Joint Chief Chairman Joseph Dunford’s warning that the line between peace and war was blurring. But it didn’t go over well with all audiences, Wesley said, though he didn’t specify who.

“We talked about the competition space in there and we were counseled, maybe you should make that a separate topic,” Wesley recounted yesterday. “And our argument is: No! it’s absolutely intimately linked to the conflict that follows.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.