FARA: Army Awards 5 Design Contracts; Winner Enters Production in 2028

Posted on

Just 13 months after Army leaders put a new scout aircraft on the fast track — and two months ahead of its original target date to award contracts — the service has chosen five firms to design potential Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft. The winning companies are a who’s who of usual suspects with some interesting twists:

- AVX Aircraft (Fort Worth), an innovative design firm that’s now teamed with L-3 (Waco), which provides actual manufacturing capability AVX has lacked;

- Bell (also Fort Worth), whose gamble on offering an upgraded conventional helicopter seems to be paying off (see more on that below);

- Boeing (Mesa, Arizona), the aerospace titan that builds the Army’s AH-64 Apache and CH-47 Chinook;

- Karem Aircraft (Lake Forest, California), known for innovative designs and small-scale projects but not mass production;

- Sikorsky (Stratford, Connecticut), a Lockheed subsidiary that builds the current UH-60 Black Hawk and is now developing radically innovative compound helicopter designs.

Particularly telling is the inclusion of Bell, which in the past made the Army’s previous scout helicopter, the OH-58 Kiowa, and is now a leading contender to replace the UH-60 transport with its V-280 Valor tiltrotor. Rather than scale down its tiltrotor technology to build a light scout, Bell bet it could meet the Army’s requirements with a conventional helicopter — specifically a scaled-down version of its still-in-testing Bell 525 — arguing it would have higher reliability and lower cost than a high-speed aircraft like Sikorsky’s propeller-helicopter hybrid, the S-97 Raider. That gamble paid off: The Army’s at least willing to consider a traditional design, if only to give itself a safe fallback if more radical ideas can’t be made to work on schedule and on budget: The Army wants FARA to cost no more, on average, than the current AH-64 Apache, about $30 million apiece.

The Army said it had received eight proposals and only rejected three that didn’t meet its minimum mandatory requirements. Those requirements? To simplify logistics, FARA has to use some prescribed government-furnished equipment: a specific 20 mm gun, a particular missile launcher, and the GE T901 Improved Turbine Engine. To survive against Russian or Chinese advanced air defenses, FARA must also achieve a minimum speed of 205 knots (235 mph) and have a maximum rotor diameter of 40 feet, allowing it to sneak down city streets and hide behind small obstacles.

Sikorsky’s S-97 Raider, a leading candidate for the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft, shows off its agility.

The Need For Speed

Just 10 months from now, in February 2020, the Army will pick two of these five companies to actually build competing prototypes, with the final winner to enter low-rate production in 2028. It’s not clear when the first operational unit will be fielded, but that’s because the Army is still figuring out what that unit will look like– part of a top-to-bottom relook at how the service organizes and fights.

That nine-year timeline from PowerPoint to production is blisteringly fast for a Pentagon procurement program, but the Army wants to go faster.

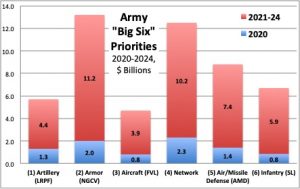

LRPF: Long-Range Precision Fires. NGCV: Next-Generation Combat Vehicle. FVL: Future Vertical Lift. AMD: Air & Missile Defense. SL: Soldier Lethality. SOURCE: US Army. (Click to expand)

“Milestone C right now is 2028,” Col. Craig Alia told me and another reporter, “[but] we’re looking at every opportunity to accelerate the process to get it earlier.”

Alia is chief of staff for the Army’s Future Vertical Lift Cross Functional Team, one of eight such teams created to accelerate Army modernization efforts, from thousand-mile hypersonic missiles to 6.8 mm assault rifles. Some Army modernization projects are actually moving even faster than FARA — Microsoft is already building VR targeting goggles for foot troops, for example — but FARA’s timeline is extremely ambitious to develop a new combat aircraft.

A lot of time is saved by cutting red tape. “What’s exciting about the new process the Army has put in place with the Army Futures Command and the Cross Functional Teams,” said FARA program manager Dan Bailey, “[is] in basically a year’s period of time, we’ve gone from concept to an approved set of requirements, to developing an innovative approach to contracting … to having industry propose [designs].”

That normally would take years, he said, but “we’ve done everything we can do to remove the pauses.”

The Army retired the OH-58 Kiowa scout without a replacement. FARA, the Future Attack Reconnaissance Aircraft, is meant to fill that gap.

The five contracts are Other Transaction Agreements (OTAs), specifically designed to avoid any break in the program. Rather than contract for a design, then write a new contract to build a prototype, then write a third contract for production, the Army has contracted each of the five firms for the whole process, from design through delivery: The winner will simply execute the full contract as written, while the Army will exercise a cancellation clause for the losers. (A similar structure was used for the Joint Multi-Role Tech Demonstrators, with the winners becoming the Bell V-280 and the Sikorsky-Boeing SB>1 that are now vying to replace the UH-60 Black Hawk).

The contract also has plenty of leeway to either accelerate or slow down, depending on how technology progresses. Even the Improved Turbine Engine, currently mandatory, could be waived if that program doesn’t deliver usable engines in time.

That flexibility is critical, because, as hard as it is to streamline a dysfunctional bureaucratic process, it’s even harder to make engineers invent a new aircraft on a schedule. That’s especially true if the Army rejects Bell’s conventional-helicopter design in favor of something more radical. The crucial test for the Army’s high-speed approach to its future scout is still to come.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.