F-35’s First Combat Strike Won’t End Debate

Posted on

WASHINGTON: The first-ever real-world strike by an F-35 Joint Strike Fighter is a big symbolic moment, as the Pentagon is well aware. It’s also a milestone towards making the F-35 a close-support aircraft to bomb targets threatening US ground troops, replacing the beloved A-10 Warthog.

That’s why the military not only had a press release out the same day — normally strike announcements take much longer to percolate through the bureaucracy — but also high quality video of the Marine Corps F-35B taking off from the amphibious assault ship USS Essex, filmed from at least four different angles. Clearly this was a well-planned publicity blitz. None of this, however, will quiet the F-35’s detractors.

Today’s strike hit an undisclosed target in Afghanistan in support of friendly ground forces. But penetrating Afghan airspace isn’t the challenge the F-35 was built for. In fact, the anti-aircraft threat there is so non-existent the Air Force is strongly considering buying propeller planes to conduct strikes, basically World War II technology updated with modern electronics for targeting and communications.

The F-35, by contrast, is a stealth jet designed to evade radar and penetrate advanced anti-aircraft defenses at high speeds. None of that is necessary in Afghanistan. In fact, the F-35B used today appears to have had some kind of pod or extra fuel tank hanging from its belly, breaking its clean radar-deflecting lines and compromising stealth.

So what would be a good test of the F-35, if Afghanistan was not? The true test would be a strike into the advanced defenses known as Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) systems, but those are exclusive to great powers. Fortunately, we are not at war with China or Russia, and hopefully we never will be. (The most effective weapon is one that deters a fight from ever starting).

Underside of the F-35B as it does a vertical landing back on the USS Essex. Note what appears to be a pod mounted underneath.

The best test we have had so far is in the Air Force’s Red Flag exercises last year, in which F-35As — the Air Force variant — consistently got the jump on older-model fighters in one simulated victory after another. For every F-35A “shot down,” the stealth fighters shot down at least 15 non-stealthy planes. Almost as important, the Air Force said, its F-35As proved highly reliable, with mission capable rates over 90 percent.

This performance is an important counter to criticism of the F-35 as a poor fighter with poor reliability, although of course skeptics are unlikely to trust the Air Force’s claims. The critics point to the plane’s long and troubled development, which one Pentagon procurement chief admitted was “acquisition malpractice“; the previous and current program managers have both sharply criticized prime contractor Lockheed Martin. The critics argue the physics of its design compromise classic aerodynamic principles in the name of stealth, which they say make it bad at dogfighting, because it lacks agility; at bombing, because it lacks payload; and at close air support, because it lacks the A-10‘s ability to go in low and slow.

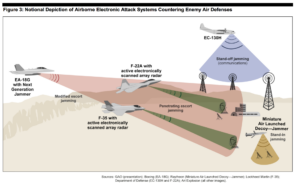

While older aircraft like the EA-18G and EC-130H jam enemy systems from a distance, stealthy F-22s and F-35s can slip through air defenses to conduct electronic warfare at close range.

The proponents counter that the F-35 program has reformed and gotten on track. They say its combination of stealth, sensors, and high-powered computing make it superbly able to strike well-defended targets or ambush enemy aircraft from long range without having to dogfight, as at Red Flag. Rather than judging the F-35 by traditional air combat criteria, the military often speaks about it as a cyber and electronic warfare weapon. The Air Force chief of staff, Gen. David Goldfein, even called it “a computer that happens to fly.”

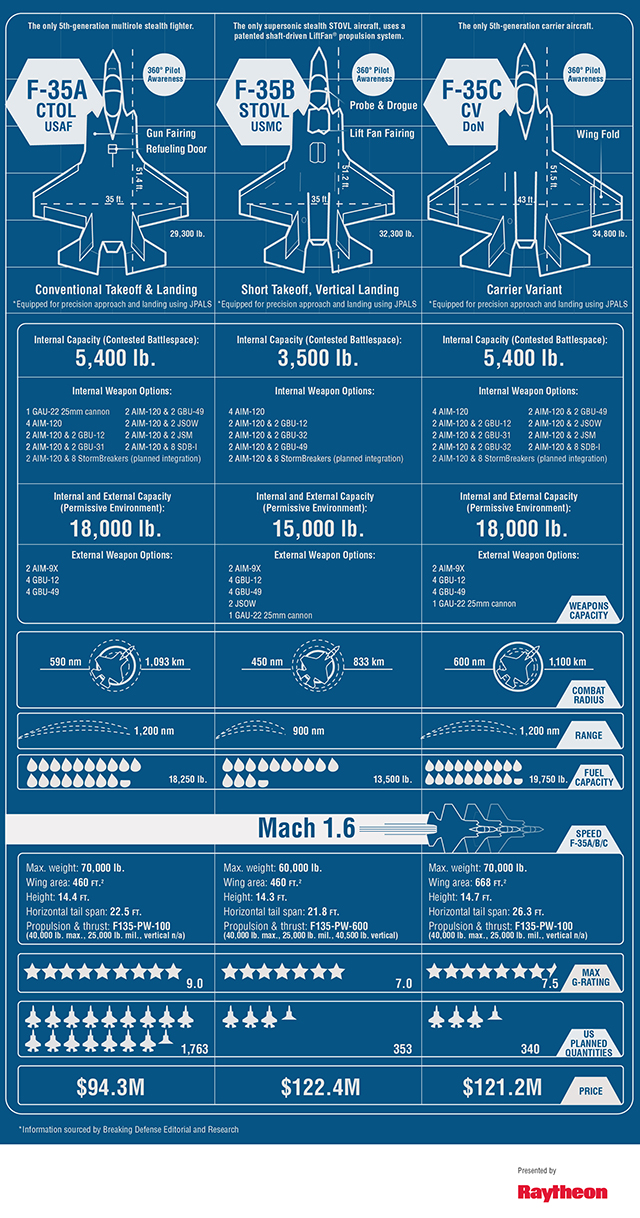

As the fighter’s three variants — the Air Force F-35A, Marine Corps F-35B, and Navy F-35C — enter mass production and move into wider service with the US military and its allies from Australia to Great Britain, we’ll get a lot more data on maintenance and reliability. But the true test of the F-35 won’t come until it faces high-tech air defenses.

Colin Clark contributed to this story.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.