Erdogan’s Turkey: The Role Of A Little Known Islamist Poet

Posted on

When President Trump announced that the US had recognized Jerusalem as Israel’s capital, the region prepared for violence. Aside from a few days of sporadic protests, relatively little happened. Most Arab leaders – Saudi Arabia chief among them – took the decision in their stride. The one major exception was Turkey. This intriguing op-ed explores why the NATO ally has reacted as it has. Read on! The Editor.

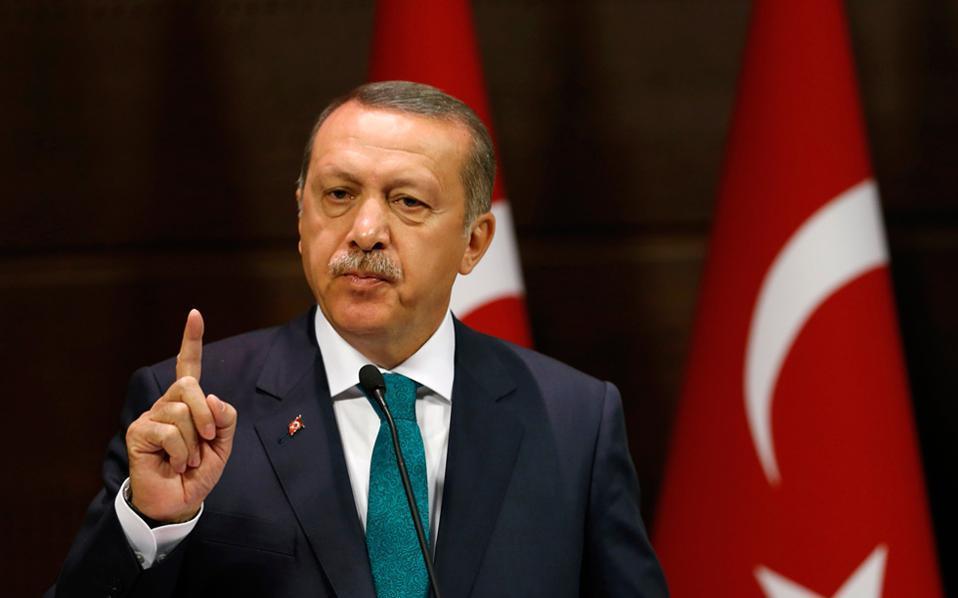

Turkey’s President, Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, has a penchant for conspiracy. In recent years, he has frequently blamed foreign “masterminds” for all problems plaguing Turkey and the Muslim world. Following President Trump’s announcement, Erdoğan called an emergency summit of the Organization for Islamic Cooperation, benefiting from his country’s rotating presidency of that organization, which enabled him to cast himself as the leader of the Muslim world.

Speaking two days later at an award ceremony, Erdoğan outdid himself: “if Jerusalem goes, we will lose Medina. If Medina goes, we will lose Mecca. If Mecca goes, we will lose the Kaaba!”

Where does this vitriol come from? Dismissing it as rhetoric from an embattled regime would be a mistake. Anti-Israel animus and a penchant for conspiracy theories involving global Jewry have been a constant in Erdoğan’s shifting domestic alliances and foreign policy initiatives.

Erdoğan’s December 15 speech was symbolic indeed: the occasion betrayed more than meets the eye. Erdoğan uttered his warning at the awards celebrating the Islamist poet and writer Necip Fazıl Kısakürek (1904-83), who was the intellectual mentor not only for Erdoğan, but for a large portion of the current political elite in Turkey.

Kısakürek was once a marginal figure in Turkey. While educated partially in France, Kısakürek grew to abhor the West, and to see it as the root of all evil. But like many contemporary Islamists, he incorporated European fascist ideas, two of which stand out. The first was his rejection of democracy, and his advocacy instead for a political system led by an “exalted ruler” – a totalitarian Islamist and nationalist regime built on Sunni Islam and Turkish ethnicity, which envisaged the ethnic cleansing of other, less desirable groups.

Second, Kısakürek harbored a strong hatred for Jews and their imagined sidekicks, the freemasons, who he believed were in cahoots, hell-bent on destroying Turkey. This hatred is obvious throughout his work, but was so strong that he devoted an entire book to the subject. He viewed the expulsion of Jews – and a Turkish community of Jewish converts to Islam called the dönme – as critical to the country’s survival. Once this cleansing was complete, Turkey would “shine like a diamond.”

This repulsive and once marginal figure is now widely celebrated: Turkish cabinet ministers regularly sing his praises. Erdoğan himself once cited Kısakürek as the single person who influenced him the most, and his December 15 appearance was no exception: he makes a point out of appearing at events honoring the person he calls his “master,” and reciting his poetry.

Following the collapse of Turkey’s Middle East policies and the July 2016 failed coup, Erdoğan appeared to tone down his Islamist ideology and embrace a more nationalist persona. He also normalized relations with both Israel and Russia. And while the Turkish Jewish community has not been targeted for reprisals, the general atmosphere has led it to shrink rapidly.

In the midst of a sputtering economy, Erdoğan knows his Islamist ideology does not win elections. This is why he is in the midst of trying to co-opt the opposition Nationalist Action Party ahead of elections in coming years. While Israel-bashing will hardly cost Erdoğan any votes, it is not an issue that truly animates the Turkish public. Erdoğan’s hyperbole on Jerusalem is indicative of a broader trend: how the Islamist ideology that Kısakürek represents has become mainstream in Turkey. It is no longer marginal; in fact, it is actively propagated by many of Turkey’s media, schools and mosques. This worldview also forms the backdrop for Turkey’s central role for many Islamist organizations globally, which National Security Advisor H.R. McMaster spoke of on December 11.

Erdoğan’s reaction to the Jerusalem decision should not be construed as being only about Erdoğan. It is an indication of the country’s shifting identity. Finding ways to punish Erdoğan would not solve the deeper problem: Turkish society is rapidly slipping its western moorings. Whatever happens at the political level, it is time to take the long view, and devise ways to counter the ideological drift of this critical ally into a toxic blend of Islamism and ethnic nationalism.

Svante Cornell is director of the American Foreign Policy Council’s Central Asia-Caucasus Institute and policy advisor to the Jewish Institute for National Security of America’s Gemunder Center.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.