Electronic Warfare Trumps Cyber For Deterring Russia

Posted on

CENTER FOR STRATEGIC & INTERNATIONAL STUDIES: NATO’s plans to defend the Baltic States are “inadequate” because they don’t take full account of Russia’s electronic warfare capabilities, a leading expert warns.

Roger McDermott

The Russians are hardly invincible, Roger McDermott emphasized at CSIS on Monday. The story of them “shutting down” the Aegis radar on the USS Cook in 2014 is pure propaganda, he said, and their soldiers let slip secrets on social media just as ours do over Fitbit. But nevertheless, Russian EW forces are numerous, well-equipped, well-coordinated with other combat arms like air defense and artillery, and above all honed by years of electronic combat — all things their US Army counterparts are not.

That makes it “more vital and pressing” to rebuild western electronic warfare than to build up new capabilities in cyber warfare, McDermott writes. Ironically, McDermott’s study was sponsored in part by the Estonian government, which has focused on cyber ever since Russian hackers took down its internet in 2007.

Russian Krasukha-2 radar jamming system, reportedly deployed in Syria

Russian Successes

Since McDermott first presented his paper in Estonia last fall, Russia has shown off its electronic warfare skills in combat once again, this time in Syria. In early January, a still-unknown party launched 13 armed drones against the Russian HQ at Hmeimin airbase and against the Russian naval base at Tartus.

Sam Bendett

In contrast to previous attacks by old-fashioned mortars that killed two Russian servicemen, none of the drones reached their targets. Seven were destroyed by the Pantsir (Shell) anti-aircraft system, which fired expensive missiles at the cheap drones. The other six were neutralized electronically, which could mean anything from sending them false commands — a hybrid cyber/electronic warfare attack — to old-school, brute-force radio jamming of their GPS receivers or control links so they couldn’t navigate. Whatever the EW technique used, it was effectively free.

“The attempted drone swarm attack (is) way better than a snap inspection (or) simulating it or trying to exercise,” McDermott said. “One of the reasons the Russian armed forces… are booming with confidence at this point is because they’re gaining such operational experience.” Even though the drones used in Syria were “rudimentary,” McDermott said, defeating them was still good real-world practice, not only for using electronic warfare itself but for using EW in concert with other arms, in this case air defense.

It was clearly a layered defense integrating jammeres with radar and anti-aircraft missiles, agreed Samuel Bendett, a CNA expert on Russian military technology. “In this case, the 13 drones were located, identified, then jammed/hacked, (and) those that broke through were destroyed by an air defense system – all long before these drones reached their intended targets,” Bendett told me.”What’s evident now is that Russia’s plan to more closely integrate their EW forces with air/missile defenses is coming to fruition.”

Tracked variant of the Russian Pantsir S1 anti-aircraft missile system (NATO reporting name SA-22 Greyhound)

“We can’t just strip out the EW capability and look at it separately (from) cyber, SIGINT (signals intelligence), air defense,” McDermott said. In Ukraine, for instance, Russian electronic warfare units not only jammed international monitoring drones: They also worked intimately together with Russia’s own drones and its dreaded rocket artillery batteries. Russia EW would jam some Ukrainian communications and triangulate others, finding possible targets that the drones would confirm before calling in a crushing barrage.

“The Russian military is incredibly good at killing things if it can find them, but it always historically struggles at seeing on the battlefield,” said Michael Kofman, a senior research scientist at CNA, who spoke at CSIS alongside McDermott. Electronic warfare simultaneously helps the Russians see the enemy better and blinds the enemy so they can’t target the Russians. The aim is to disrupt the entire “kill chain” — from initial sensor detection of a target, through the decision to engage, to actually hitting it — so Western airpower and long-range precision-guided weapons can’t be brought to bear.

Michael Kofman

What if the West jams back? Giving their history of grueling combat, the Russians seem confident they’ll prevail in a conflict where both sides are half-blind. That makes them less worried about how discriminate their own jamming is and whether it interfere with some of their own systems. “How do they operate without jamming themselves?” Kofman said. “The answer is they don’t, they do jam themselves.”

They also train to fight under such conditions, he said. That’s evident from the recent Zapad (West) exercises, in which the Russians conducted live electronic jamming — some of it spilling over into NATO territory, accidentally or otherwise — alongside conventional mechanized maneuvers.

Besides enhancing traditional heavy firepower operations, Kofman said, EW also gives Russian commanders the option of “non-contact operations” to jam, blind, disrupt, and demoralize the enemy without ever firing a shot — indeed, without ever violating NATO territory . Such blurring of the lines between war and peace to create a “grey zone” has become a Russian specialty in recent years.

Without the means to fight back in kind, NATO has no good choices against such grey zone tactics. Deescalate and you let Russian get away with whatever bullying, subversion, or outright annexation it was trying. Escalate and you invite the Russians to unleash their formidable conventional forces. In short, McDermott said, “on Russia’s periphery, Russia has escalation dominance.”

That doesn’t mean they can just flip a switch and remotely turn off NATO’s electronics, McDermott emphasized. “They won’t take it all out,” he said, “(but) they will build the EW component into …. making any NATO operation in the Baltic, or elsewhere on NATO’s eastern flank, as difficult, as costly, as complex, as possible….and in worse case scenario, we lose.”

Russian Borisoglebsk-2 long-range EW system

Russian Capabilities

How big is the Russian electronic warfare force? The real numbers are naturally a state secret, but Kofman was willing to help me make a rough estimate of nearly 9,000 in the ground forces alone, with thousands more in the navy and air force. In stark contrast to the United States, where the main remaining EW force is Navy aircraft — Growlers and Prowlers — and the Army has almost nothing, Russia’s most powerful EW is in the Army.

The big deal isn’t just how big these Russian EW forces are: It’s how intimately they’re integrated with combat units and thus combat operations. “It’s found throughout every arm of service, every branch of service, it’s almost impossible to avoid EW capability, which very much contrasts to western militaries,” said McDermott. “If we look at the staff officers in a United States brigade, we’re going to find two, maybe three maximum.”

In stark contrast to the US, since 2008, every single Russian combat brigade has been given its own electronic warfare company: McDermott estimates its strength at “150 to 180 EW specialists,” while Kofman suspects it’s less than half that, 75. Even at a compromise guesstimate of 100 per company, with one company in each of 28 motor-rife and tank “separate brigades,” that’s 2,800 EW specialists just in frontline tactical units alone, equipped with jammers that reach out roughly thirty miles (50 km).

courtesy Roger McDermott

What’s more, there are five independent “EW brigades” — really more like battalions at 1,200 troops apiece — that have more powerful equipment, with ranges of “several hundreds of kilometers” according to McDermott. These brigades add another 6,000 personnel. That’s not counting the inevitable overhead of troops not currently in a unit, for example because they’re students or instructors at advanced technical schools.

Now, not all these soldiers are chess-playing Russian geniuses. One of the best sources on the ostensibly covert war in Ukraine is social media posts by Russian troops, often complete with geographic metadata that clearly places them on the wrong side of the border. Even sensitive electronic warfare equipment shows up on shared photos.

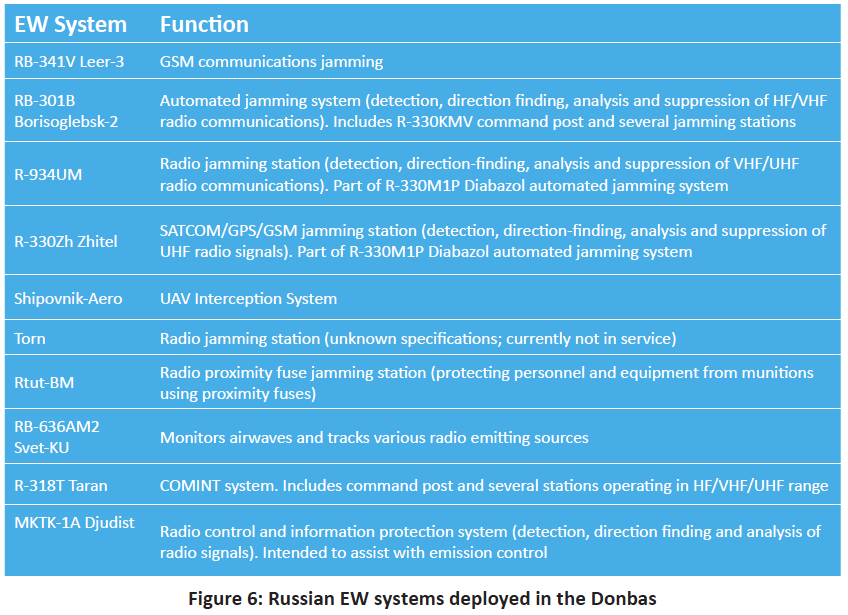

“When you look at the social media you can find almost all of the known systems, Russian EW systems, popping up somewhere in Donbas,” said McDermott, “maybe not for terribly long but they were certainly there and certainly experimenting.” The Russians appear to be putting all their technology through a trial by fire in Ukraine to see how well it works and what tactics are best.

Even for the majority of units that don’t get to go to Ukraine, said Kofman, the integration of electronic warfare into every frontline brigade gives conventional combat-arms commanders first-hand experience working with EW personnel, technology, and tactics.

Russian generals with Vladimir Putin and Bashar al-Assad

Compared to Western soldiers, lower-ranking Russian troops may lack initiative at the lower levels, but that’s not true for higher echelons of command, especially among those blooded in Ukraine, McDermott said: “The Russian generals that are rotating in and out of Donbas have a similar level of initiative, in my view, to their western counterparts.”

It’s also worth noting that the Russian army’s EW branch has its own general officers, with the equivalent of an American two-star as the branch chief (Major General Yuriy Lastochkin). A 2016 article in the official journal of the General Staff even proposed elevating electronic warfare from a support function to a full-fledged combat arm. By contrast, the highest-ranking electronic warfare officer in the United States Army is a colonel, and US Army electronic warfare is being subsumed into the newly created cyber branch.

Perhaps this lack of institutional advocates explains why US Army electronic warfare forces still don’t have a long-range offensive jammer, only short-range systems to neutralize roadside bombs, although some stopgap systems are being fielded. Meanwhile the Russian army has an arsenal of electronic warfare gear and plenty of troops experienced in using it.

Roger McDermott graphic

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.