Do Marines Have To Hitchhike At Sea? The Real Story

Posted on

Dutch navy Captain Renee Lucykx watches the USS Arlington from the bridge of the Dutch ship Johan De Witt.

WASHINGTON: Is the US Navy really so short of warships that Marines must catch a ride on foreign vessels, like heavily armed hitchhikers? The answer is, well, sort of. Where there’s smoke, there’s often fire — the Marines definitely could use more amphibious warfare ships — but on this story, politicians, lobbyists, and some of my media colleagues have blown some extra smoke.

Marines debark a V-22

There’s a story in how the story has evolved. On June 14, the Marine Corps Times, a Gannet publication mostly read by the military, published “Marines to deploy aboard European allies’ ships.” Starting this fall, the story said, US Marines would embark on British and Italian ships, and test out Danish, French, and Spanish ones. Along with land-based Marine Corps task forces, said Brig. Gen. Norm Cooling, the allied vessels can help make up for a longstanding shortage of US amphibious warships in the Mediterranean. The key concern, reportedly, will be ensuring the Marines’ high-powered but heavy V-22 Osprey can fly off European flight decks.

A week later, when the story got picked up by Gannett’s flagship, USA Today, the headline got streamlined to “Marines looking at deploying aboard foreign ships” (emphasis ours). The Daily Caller promptly added snark: “Budget Problems May Force Marines To Hitchhike With The French” (emphasis ours; contempt for “cheese-eating surrender monkeys” implicit in the original). On Monday, the Amphibious Warship Industrial Base Coalition — which is funded by shipbuilder Huntington-Ingalls — declared that “media reports of the U.S. Marine Corps being forced to be potentially deployed aboard foreign allied ships due to a shortage of U.S. Navy amphibious warships are deeply disturbing.”

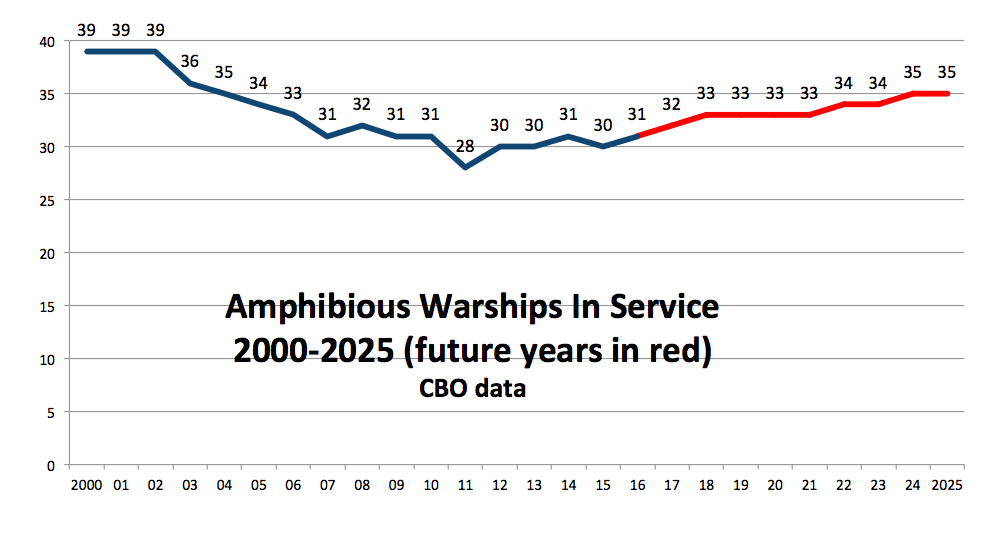

“The Marine Corps has a warfighting requirement for 38 amphibious ships. Today, the Navy has 30 such vessels in service,” House seapower subcommittee chairman Rep. Randy Forbes told us in a statement. Forbes has pushed hard and successfully for amphibious forces, helping secure funding for an additional (Ingalls-built) San Antonio-class ship. “Allowing the continued atrophy of the Navy-Marine Corps team’s amphibious capacity is simply not an option.”

Rep. Randy Forbes

“The ride-sharing is a result of the shrinking amphibious fleet,” said one House Republican aide. “Partnership capacity building is great and important, but that’s not what this is. It’s a reaction to a capacity shortfall that the Marines don’t want, i.e. we don’t have enough amphibs to go around.”

To talk about the “atrophy” of a “shrinking” amphib fleet isn’t entirely fair, however. The fleet bottomed out at 29 amphibs back in 2011. It’s now at 30. With new San Antonio amphibs and the even larger America-class entering service, the Navy’s 30-year shipbuilding plan says the amphib fleet will rise to 33 ships in 2018 and to 36 in 2026. That’s not 38, but the military rarely meets its full “requirement” for anything. “33 amphibious ships accepts risk,” Marine spokesman Col. Sean Gibson told us, “but has been judged to be adequate in meeting the needs of the naval service, within today’s fiscal limitations.”

Forbes, however, considers the 30-year plan a fiscally unrealistic “fantasyland.” The risk of sequester does call all its figures into question, especially the longer-term ones.

So there’s a much larger, intensely political debate here over the size of the Navy and the US military in general, a debate of which this specific expedient in the Mediterranean is both symbol and symptom. But it’s also easy for anxieties to get overblown.

French aircraft carrier Charles de Gaulle en route to Libya during the 2011 air war.

First and foremost, working with allies is a good thing — even if they’re French. In fact, France boasts one of the most powerful militaries left in Europe, an impressive combat record, and a proven willingness to fight. The French were the first ally to join us in striking the Islamic State, and in 2013 they had pushed hard to strike the Syrian regime after its use of chemical weapons, only to be left hanging by Obama. French squadrons have flown off US carriers to train. As for the Italians and British, they’ll both be flying F-35B jump jets — the same model used by the Marines — allowing for tight integration among the three nations’ cutting-edge aircraft.

Second, US Marines embark on allied warships all the time, and vice versa. They’ve been doing it “for decades,” Col. Gibson said. “Allied ships will not supplant the freedom of action or flexibility offered by US amphibious ships,” he said (emphasis ours), “[but] having capable partners with whom we can operate in tandem increases response options.”

Admittedly, such “cross-decking” is normally about training and interoperability: Of two retired admirals I talked to, neither could think of a time when Marines embarked on foreign ships for an operational deployment. But deploying together is not a radically new idea.

“This is a logical extension of a two-way allied relationship,” said retired Vice Adm. Peter Daly, head of the US Naval Institute.

Bryan Clark

“They should be doing this anyway, and they have been doing it,” said Bryan Clark, a retired Navy commander now at the Center for Strategic and Budgetary Assessments (CSBA). “They have been pursuing this as part of coalition-building for some time,” said Clark, who until recently served as a senior aide to the Chief of Naval Operations.

“Most nations around the world don’t have marines,” Clark said, not in the US sense. They may have specially trained army troops, lightly armed “naval infantry,” or elite commandos like Britain’s famed Royal Marines, but they don’t have a seaborne combined-armed force with infantry, tanks, artillery, and its own aircraft. (In some ways the Marines are the world’s only self-contained joint force, but don’t tell the Pentagon.) So our allies are eager to train with and learn from with our unique Marine Corps, Clark said, and we learn how to better operate with them.

That said, Clark acknowledged, this particular initiative is indeed driven by a gap between the supply of US amphibious warships and the demand. But the problem isn’t just the supply being low: It’s also that demand has spiked.

“This is kind of a short-term expedient as a result of various crises,” Clark told me. Especially after the deadly 2012 attack on the US consulate in Benghazi, commanders have been alert for threats to US interests that might require a sudden response, for example to evacuate an embassy — a specialty of the Marine Corps. The rise of Boko Haram in Nigeria, Clark said, is a particular concern.

With unrest from West Africa to the Middle East, US response forces are spread thin. Since 9/11, the Navy has stopped assigning amphibious ships to patrol the Mediterranean. Instead, we’ve covered the region with whatever vessels were passing to or from missions in the Mideast. But no one ship can simultaneously cover the Persian Gulf and the Gulf of Guinea. There’s just too much Africa in between.

“The shortfall in amphibious ships has been going on for a long time. It’s not a sudden new thing,” said Clark. “The big difference is the nature of the demand has changed.”

Joint High Speed Vessel

Traditionally, Clark explained, Africa was seen as a low-threat theater. Most deployments there involved showing the flag, training with friendly nations, chasing pirates, and the odd special forces raid. Those missions didn’t require a well-armed warship, just something that can carry supplies and operate aircraft. So the Marines and Navy have been working on a flotilla of innovative substitutes: capacious converted oil tankers called Mobile Landing Platforms (MLPs) and Afloat Forward Staging Bases (AFSBs); a light transport, based on commercial ferries, called the Joint High-Speed Vessel (JHSV); and land-based Special Purpose Marine Air-Ground Task Forces (SP-MAGTFs).

“The use of auxiliary platforms does not reduce the USMC requirement for 38 amphibious ships,” Col. Gibson said, “[but] these vessels will help address an increasing demand for persistent forward presence and sea-based operations, freeing amphibious ships to concentrate on their core mission.”

But just as the unarmed auxiliaries are entering service in numbers, the environment is becoming less amenable to them. In particular, “low-threat” Africa is increasingly dangerous, putting a premium on the full capabilities of an amphibious warship — especially for self-protection in hostile waters. Now, said Clark, “the same region now needs a warship because you’re concerned about the security threat.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.