DepSecDef Work Details 2017 Budget: Offset Just Beginning EXCLUSIVE

Posted on

Robert Work

UPDATED: Adds DepSecDef Explanation For Additional LCS

PENTAGON: “We don’t have enough money to do everything we want to do,” Deputy Defense Secretary Bob Work told me in an exclusive 85-minute interview in his E-Ring Pentagon office. “So what we’re doing this year, Sydney, is we are trying to prepare as many demonstrations on advanced capabilities as we possibly can for the next administration to determine…the way they want to go.”

[Click here for our complete coverage of the 2017 budget and click here for Work’s in-depth discussion of the Offset Strategy]

“We need another year of really thinking about the Third Offset Strategy before we would ever make any firm bets,” Work said of the nascent effort to stay ahead of China and Russia. “For the next year, what we’re doing on the Third Offset is really working with the (House and Senate Armed Services Committees) and with the services to develop the operational concepts that would help us determine what are the key bets we’re going to make.”

In other words, the 2017 budget plants seed corn for the next president to reap or winnow out. It’s almost a preview trailer for the 2018 budget, which will be almost completely written by Obama officials before the next administration is sworn in and can make last-minute adjustments. Fiscal realities mean nobody is going for a grand Hail Mary reform in the last 12 months of the Obama administration.

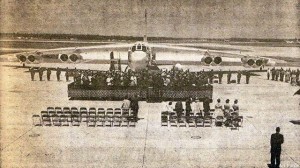

That’s why Defense Secretary Ash Carter’s Strategic Capabilities Office focuses on relatively small investments that get more use out of existing assets, like repurposing the 54-year-old B-52 as an “arsenal plane” and modifying traditional cannon to fire guided Hyper Velocity Projectiles. That’s why, with the significant exceptions of the tri-service F-35 Joint Strike Fighter and the Air Force Long-Range Strike Bomber — which Work says fit the Offset Strategy even though they were conceived before it — the imperative to counter China and Russia is not launching any major modernization programs, but rather upgrading and upgunning existing systems.

The Air Force’s B-52 entered service in 1962.

The worsening strategic situation imposes three priorities on the budget.

“We have a resurgent Russia and a rising China,” Work told me. “So first things first, let’s start to shift away from a focus on counterinsurgency and focus on these high-end adversaries.”

“The second thing is take a hard look at the balance between modernization, force structure and readiness in each of the departments,” he continued. “The third thing is…how can we be innovative and bring in a whole lot of new capabilities that will allow a force that is essentially flat become more effective?”

Those three priorities drive some painful trade-offs in each of the three military departments — Army, Air Force, and Navy (including Marines) — across the three dimensions of modernization, readiness, and force structure. The Army’s 2017 budget boosts near-term readiness at the expense of long-term modernization, while holding the line on force size. The Air Force pays to keep (for now) A-10 “Warthog” squadrons it once wanted to disband, keeping up the size of the force while cutting back on modernization. Conversely, the Navy buys fewer ships in order to afford more aircraft, missiles, and upgraded equipment to go on the ships it has.

“In the case of the Navy, what we did was we took force structure and we bought capability. Now, in the Air Force it was entirely different,” Work said. “In the Air Force, we took a little modernization to get back squadrons.”

“We thought that we could take some near-term risk in the modernization on the Army,” Work continued. “Given the choice between the two, readiness is more important right now because the M1A1 and the Bradley and all (are) pretty darn good stuff.”

M1 Abrams tank

The Army: AirLand Battle 2.0

Physically, if not intellectually, the Army of 2015 is still the Army that Reagan built — and the return of the Russian bear isn’t changing that. With upgraded electronics and, in many cases, heavier armor and bigger engines, the “Big Five” of the 1980s buildup remain formidable, as Work said: The M1 Abrams tank, the M2 Bradley troop carrier, the Patriot missile, the UH-60 utility helicopter, and the AH-64 Apache attack helicopter.

The Army’s biggest “new” weapons programs are not that new, either: The Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle is essentially a turretless Bradley, and the Joint Light Tactical Vehicle is a nimbler version of the Afghan War’ M-ATV truck. All-new weapons like the Future Combat System, Ground Combat Vehicle, and Armed Aerial Scout have repeatedly been canceled or stillborn.

Army modernization matters, Work acknowledged, but we’re still laying the intellectual ground work for what it should be. “Essentially, what I’ve asked of the Army is, what does AirLand Battle 2.0 look like?” he said, referring to the original AirLand Battle doctrine that underlay both the Big Five and two successive defeats of Saddam Hussein. “It’s not for us to dictate to the Army what their operational concepts are, (but) we know that there’s going to be a lot more EW (Electronic Warfare), a lot more cyber attacks, and a lot more precision fires that you’ve never had to deal with before.”

“They’re looking at the lessons learned in Ukraine, where the Russians used UAVs and a lot of artillery, a lot of electronic warfare,” Work said. A Strategic Portfolio Review (SPR) is underway, he said, and “in 2018 we’ll be making some recommendations on how to improve the Army’s ability to do cyber, EW, and fire and maneuver on these high technology battlefields. ”

So the Army is investing considerable intellectual capital in its future — but when will it get actual money? Not much and not soon. “We’re comfortable with the force structure in the Army. We are not comfortable with either the modernization or readiness accounts,” said Work. “But given what’s happening in the world, we’re going to focus on readiness.”

An A-10 “Warthog” firing its infamous 30 mm gun.

Air Force: Warthogs Stay

Like the Army’s Big Five, the Air Force’s unlovely but powerful A-10 Warthog is a child of the late Cold War, designed to annihilate down Soviet tanks. Now a resurgent Russia and an intransigent Congress have convinced the Pentagon to keep it, for now. Instead of phasing out the A-10s and replacing them with the stealthy F-35, the Air Force will keep the old warhorses in service until 2022.

Work dismissed the argument that the A-10 is irreplaceable — that its heavy armor, powerful cannon, and low-and-slow flight allow it to support ground troops the way thoroughbred fighters can’t. “Right now, given the demand around the world, a tactical fighter squadron is a tactical fighter squadron is a tactical fighter squadron,” he said. “You need to be able to deliver precision ordinance anywhere.” The critical difference, he added, is that the A-10 is much more likely to get shot down by advanced air defenses than a stealth fighter.

So the issue is simply numbers. War plans require 54 tactical fighter squadrons in the Air Force, Work said. “In 2015 what the Air Force said is… we would like to temporarily go down to 49 tactical fighter squadrons by retiring the A-10, and use that money to accelerate modernization, (specifically) to buy F-35s faster so they could get back up to 54 more capable squadrons.”

“In 2015, it was a totally righteous call,” Work said. “We were expecting to be down to 1,000 troops in Afghanistan by the end of 2016. Russia had not illegally annexed the Crimea.”

“Congress said no in 2015. We asked again in 2016; they said no,” Work said (referring to the budgets being voted on, not the year of the vote). “So now in 2017, we’re saying okay, we have new facts on the ground.”

In this budget plan, “we’re going to stay at 54 (squadrons) because that’s what the demand is saying that we need, folks, for the counter-ISIL fight and in Europe,” Work said. Instead of disbanding Warthog squadrons in the near term and then eventually creating new F-35 squadrons, he said, the Air Force will retain A-10s until F-35s can replace them. (We will) retire them by 2022,” he said, “but we will not retire them until an F-35 squadron can replace it one for one.”

There’s actually a 55th squadron, but it’s paid for out of the European Reassurance Initiative (ERI) rather than the base budget. It’s a squadron of F-15C fighters out of Lakenheath, England, which the Pentagon is keeping because they cannot carry nuclear weapons, allowing commanders to move them as needed without raising Russian fears of a US first strike.

DDG-112 Michael Murphy

Navy: Big Ships, Cheap Missiles

Probably the best publicized budget shift so far was the cutback to the Navy’s Littoral Combat Ship. While the Navy convinced Secretary Carter to let it build two of the controversial lightweight vessels in 2017, rather than his initial plan for one, the rest of his stinging memorandum still stands: cut LCS and move the money into aircraft, missiles, and upgrades for larger vessels, particularly submarines.

“I’m a big fan of the LCS,” said Work, who avidly defended the program in his past life as undersecretary of the Navy. “This was not in any way, shape or form a judgment that we are not satisfied with the ship and that we’re not intent on moving to the frigate,” an upgunned version of the LCS design. “But what you will see is a down select to a single version” — instead of continue to buy two LCS designs from two shipyards — and “it will be a smaller number of frigates” than originally planned.

UPDATE BEGINS Why did the Navy restore one LCS to the budget, Work was asked at today’s DOD budget briefing? One word: competition. “The Navy came back in and said, in terms of competition, this would help” as the service moves to downselect for the new frigate. And, Work noted, the service and the Office of Secretary of Defense do want them. “If we didn’t like the ship, we would stop buying it.” UPDATE ENDS

Again, numbers matter. “The Navy has a requirement for 308 ships, (but their plan was) they would build to 321,” 52 of them LCS, Work said. “In the process of doing that, they had to sacrifice capabilities. They couldn’t buy as many airplanes. They couldn’t buy as many advanced munitions. They couldn’t buy as many UUVs (Unmanned Underwater Vehicles). They couldn’t buy as many electronic warfare systems.”

The two Littoral Combat Ship variants, LCS-1 Freedom (far) and LCS-2 Independence (near).

With the LCS cut, the fleet won’t just be smaller, it will have a different composition. “There was a requirement for 88 large surface combatants — cruisers and destroyers — and 52 Littoral Combat ships (as small surface combatants), for a total of 140 surface combatants within that 308-ship fleet,” Work continued. In this budget, with the LCS cut, he said, “there’s going to be 140 surface combatants, just as what the Navy said they needed, (but) there’s going to be 100 big boys and 40 little boys instead of 88 and 52.” That’s a force arguably better suited to high-intensity combat but less so to peacetime presence missions.

The new budget will also re-propose a plan to take aging Ticonderoga cruisers out of service temporarily for a slow-motion modernization, reducing operating costs in the process. The scheme has inspired deep skepticism on Capitol Hill. “We’ve already been told ‘no’ by the Congress, but we believe there’s no other way we can figure out how to get that $4 billion in savings,” Work said. “That is going to be an issue of contention.”

The Navy argues its cruiser modernization plan is the most efficient way to get more military mileage out of aging hulls. Likewise, the money saved by cutting LCS will go in large part to destroyer upgrades and a Virginia Payload Module that triples the cruise missile capacity of the current Virginia submarine design. Even while developing a new high-performance Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), the Navy is updating its old Tomahawks so they can hit enemy ships as well as land targets.

“We’re going to take the entire Tomahawk fleet and they’re all going to become 1,000 nautical mile range anti-ship missiles,” Work said.

The essential truth here is that we generally can’t afford to replace expensive existing systems, but we can invest in strategically cherry-picked technologies to upgrade them. It’s trying to teach old dogs new tricks, on a budget. This philosophy pervades the 2017 budget. The creed’s high temple is Secretary Carter’s personal creation, the Strategic Capabilities Office.

Strategic Capabilities: Old Dogs, New Tricks

What does the Strategic Capabilities Office do? “It’s looking at weapons that we already have and saying, ‘how can we use them differently?'” Work told me.

The Defense Department always plans on several timescales simultaneously: current operations, the next budget request, the next five years — the Future Years Defense Plan, or FYDP — and even, in various long-range plans, the next 30 years.

BAE Hyper Velocity Projectile (HVP)

“The SCO, the Strategic Capabilities Office, focuses on the first FYDP,” i.e. the next five years, Work said. When Carter started SCO, Work said, its portfolio of projects across the services totaled under $200 million a year: “Now it’s over $1 billion a year.”

By Pentagon standards, that’s not much money and not much time. So, Work said, the SCO approach is “how do you take something that we already have in the fleet, a capability we’ve already bought and paid for, and completely change its capabilities?”

“That right there is the Hyper Velocity Projectile (HVP) that would be fired out of an electromagnetic rail gun,” Work went on, pointing to an ominous conical shape on a side table in his office. “It turns out that if you put a sabot on it and use energetic powder, you can fire that thing out of a (conventional) powder gun, either a 155 millimeter howitzer or a five-inch gun on a Navy ship, (and) vastly improve our counter-cruise and counter-ballistic missile capabilities.” In short, cannon designed to shoot warships and targets ashore could become missile defense systems — at low cost.

Perdix mico-drone on Bob Work’s office table

Another example on display in Work’s office is a tiny drone, small enough to fit in your hand — or into the flare dispenser on a manned aircraft such as an F-16. “It’s called the Perdix,” he said proudly. It’s a 3D-printed airframe with electronics from a commercial cellphone, designed by students at MIT. The mini-drone still has room to accommodate different payloads, and it’s able to communicate both with other Perdixes (Perdice?) and the manned aircraft acting as their mothership.

“Just imagine an airplane going in against an IAD (Integrated Air Defense) system and dropping 30 of these out that form into a network and do crazy things.” (Work didn’t give details, but acting as sensors and/or decoys seems likely). “We’ve tested this,” he said. “We’ve tested it and it works.”

The 2017 budget intends to get as many innovations tested as possible so the next administration can choose which ones to buy in bulk — assuming they can find the funds.

Colin contributed to this story.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.