Chinese Ambassador Blasts South China Sea Tribunal

Posted on

Graphic courtesy Sen. Dan Sullivan

WASHINGTON: After a UN tribunal ruled stingingly against Chinese territorial claims in the South China Sea, Beijing reacted with its characteristically prickly mix of grandiosity and insecurity. The official Chinese perspective inverts Washington’s worldview so thoroughly it can be hard for Americans to understand: International rules are rigged, US military presence is destabilizing, China rightfully owns the whole South China Sea and is being generous to let its lesser neighbors use it at all.

When China’s ambassador to the US, Cui Tiankai, says benignly that “we are not trying to take back the islands and reefs that have been illegally occupied by others,” he’s referring to almost everything claimed by every other country in the region.

Amb. Cui Tankai

Amb. Cui laid out Beijing’s point of view beautifully yesterday afternoon, speaking (in English) just hours after the UN ruling in an unscheduled appearance at a Center for Strategic & International Studies conference. We asked some leading experts to help us parse his remarks.

“This case was initiated not out of good will or good faith,” Cui said of the Philippine appeal to the UN tribunal. “it is a clear attempt to use a legal instrument for political purposes.” What’s more, Cui said, the Philippines’ legal case was cynically coordinated with America’s “so-called pivoting to Asia,” which manifested in “mounting activities by destroyers, aircraft carriers, strategic bombers, reconnaissance planes and many others…. This is an outright manifestation of ‘might is right.’”

There’s an obvious irony here. From Washington’s perspective, it’s China and Russia that practice “lawfare,” using international bodies to delay or obfuscate while their military forces seize objectives in “grey zone” operations short of war, be it a disputed reef in the South China Sea or the entire Crimean Peninsula.

“Others are accusing China of a ‘might makes right’ approach,” said CSIS China scholar Bonnie Glaser. “The Chinese consistently portray themselves as being generous and restrained, always willing to lend a hand to their tiny neighbors. It’s hard to believe they really see it that way. Let’s recall Yang Jiechi in 2010 telling the ARF (ASEAN Regional Forum) that ‘we are the big country, and you are all small countries.’”

Yet when the US Navy steams into view, the Chinese feel like a “small country” themselves.

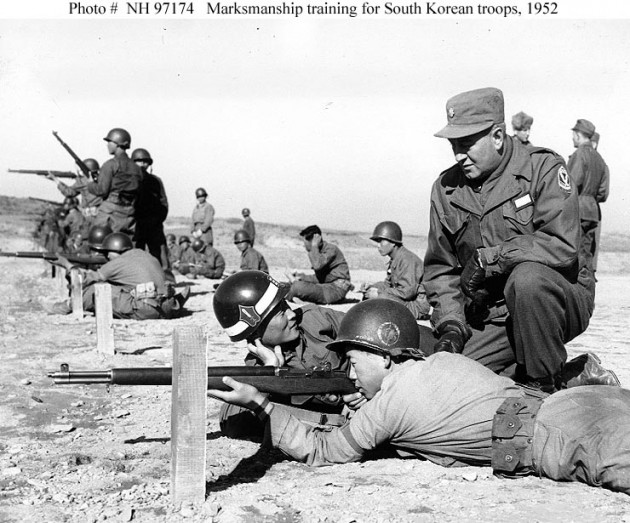

US advisors train South Korean troops in 1952.

The Fundamental Paradox

There’s an acute paradox at the heart of modern Chinese nationalism that outside observers have to understand.

On the one hand, Chinese patriots remember millennia in which the “Middle Kingdom” dominated East Asia, with neighboring nations from Korea to Vietnam paying tribute or at least lip service to the Emperor. Even in 1949, when it was struggling to protect its own capital from Mao’s advancing Communists, the Chinese Nationalist government of Chiang Kai-shek issued a map with the now-infamous “Nine-Dash Line” claiming virtually all the South China Sea. It’s this history that Amb. Cui invokes when he declares “China has long-standing sovereignty of the islands and reefs in the South China Sea, and this sovereignty had never been challenged until the late 1970s.”

On the other hand, the Chinese also remember the bitter “Century of Humiliation” which started with the Opium War, when the Royal Navy forced China, at gunpoint, to import a lethally addictive drug. Western powers extracted all kinds of concessions using superior military power and flimsy legal pretexts. The experience which didn’t predispose modern China to trust either a UN tribunal or the US Navy.

“Such an assembly of aircraft carriers, airplanes, sophisticated weapons could pose a real threat to the freedom of navigation of commercial and civilian vessels,” said Cui. “Such a concentration of firepower, anywhere in the word, would be a source of concern.”

“The Chinese bear acute and deeply felt memories…of the humiliation and weakness suffered at the hands of invasive Western powers,” said Peter Haynes of the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments. “British (and later Western) sea power fundamentally changed China, and not for the better.”

America came late to the intervention party, but US Marines joined the multinational march on Peking in 1900. In 1950 General Douglas MacArthur led an American army north towards the Yalu and advocated an invasion of Communist China, one beginning with atomic bombs. Even without nukes, American firepower killed an estimated quarter-million Chinese “volunteers” in Korea. As late as 1996, American warships sailed between mainland China and Taiwan when Beijing tried to intimidate what it considered a wayward province.

Scarred by such unpleasant encounters with US and European forces, said Haynes, “the Chinese are loath to admit that Western sea power has historically enabled the growth and stability of the global economy by ensuring the free-flow of the 95 percent of the world’s trade” — free trade which has enabled China’s rapid rise.

Chinese artificial island

Stability, Chinese Style

In Beijing’s eyes, US forces that enter Chinese-claimed airspace or waters to demonstrate “freedom of navigation” are dangerous aggression. “Intensified military activities so close to Chinese islands and reefs, or even entering the waters, the neighboring waters of the islands and reefs, these activities certainly have the risk of leading to some conflict,” said Cui.

But any US military presence is automatically suspect. For Southeast Asian countries that welcome the Americans, Cui warned, “please go to countries like Iraq, Libya, and Syria, and ask the people there” what US intervention has brought: “Be careful what you wish, you might actually get it.”

“Tensions started to rise about five or six years ago, about the same time when you began to hear about the so-called pivoting to Asia,” Cui said ominiously. “Such an exercise of so called pivoting have not brought us a more stabilized Asia… It has made conflict and dispute such a prominent issue on the regional agenda.”

Until the US showed up, China and its Southeast Asian neighbors got along as “a community of common destiny,” Cui argued. (Vietnam, which fought several wars and skirmishes with China since 1973, might disagree). Only in the 1970s was Chinese suzerainty “challenged,” Cui said, and even then the disputes were manageable and regional relationships friendly until a few years ago, when the US pivot began.

China’s island-building is not to blame, Cui insisted. “Some might put the blame on China, on China’s recent reclamation activities, but the fact is, China is the last country to do so.”

It is true that other countries reclaimed small areas of land before China did, Glaser said, but China did it much faster and on a vastly larger scale. As for the US pivot, it’s been widely criticized for adding very few new forces to those that have been in the Pacific since the end of the Korean War.

“The only reason tensions may not have been rising before (the pivot) that is China was bullying and coercing its neighbors in the region without much pushback,” said CSBA’s Bryan Clark. “When the U.S. made clear its intent to stay focused on the region, China intensified its efforts in response and its neighbors began to feel more confident in opposing Chinese pressure.”

From China’s perspective, however, America — and the UN tribunal for that matter — are meddling in what’s none of their affair. The territorial disputes should be handled bilaterally by the parties involved, one-on-one between China and its (much weaker) neighbors.

“For issues like territorial disputes, it’s only natural that the parties concerned should have direct talks with each other, (because) if you’re not a claimant, if you have no stakes there, real stakes there, how can you negotiate with other parties?” Cui said. “This case of arbitration itself is also something that could have the consequences of destabilizing the region, because it undermines the diplomatic efforts.”

“Diplomatic efforts should not be blocked and will not be blocked by a scrap of paper (i.e. the UN tribunal ruling) or by a fleet of aircraft carriers,” Cui said. “China remains committed to negotiations and consultation with other parties, this position has never changed and will not change.”

“They see ‘stability’ as a situation where China makes the rules and their neighbors abide by them,” said Clark. “The stability he advocates consists of a stable Chinese boot on the necks of its neighbors. The Southeast Asian countries may prefer some instability to Chinese hegemony.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.