Can’t Spend? Won’t Spend? 4 Lessons From NATO’s Bottom Lines

Posted on

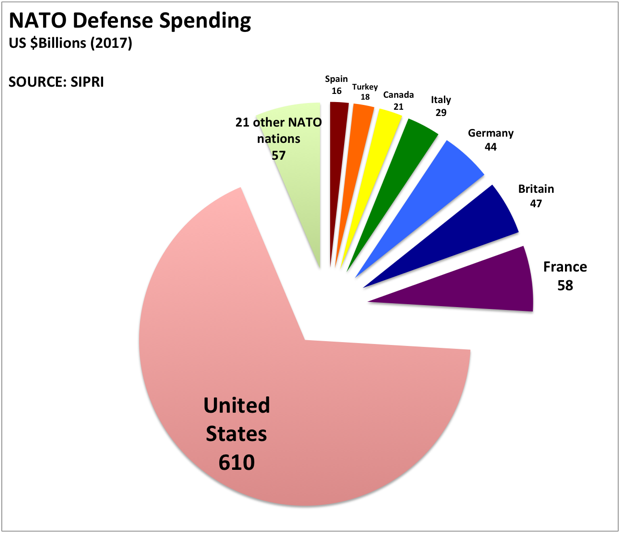

Do America’s NATO allies pay their fair share? In a word, “no” — as US presidents from Eisenhower onward have argued, including both Bush and Obama as well as Trump. America’s economy is so big, and the percentage of it we’re willing to spend on defense is so high, that it leaves our allies in the dust.

But there are many devils in them thar details, so it’s worth taking a closer look at the numbers (most of them courtesy of the CSIS study Counting Dollars). We draw four conclusions:

- Most nations don’t pay much

- Most nations can’t pay much

- Most nations spend on the wrong things

- Most nations are moving in the right direction

We go into graphic detail below.

1. Most nations don’t pay much

As President Trump has repeatedly protested, only five of NATO’s 29 members meet the alliance goal of spending two percent of GDP on defense. In order, they are

- the United States of course;

- its closest ally Britain;

- traditionally Russophobic Poland;

- economic basketcase Greece; and

- tiny Estonia, right on the Russian border.

All of these countries have deeply rooted historic reasons for higher spending. That includes Greece, which sees its main threat as fellow NATO member Turkey. None of these countries, not even the US, meets Trump’s proposed target of four percent.

(Note that CSIS doesn’t count Poland as meeting the threshold because its estimated spending is 1.99 percent of GDP. We’re willing to give them the 0.01).

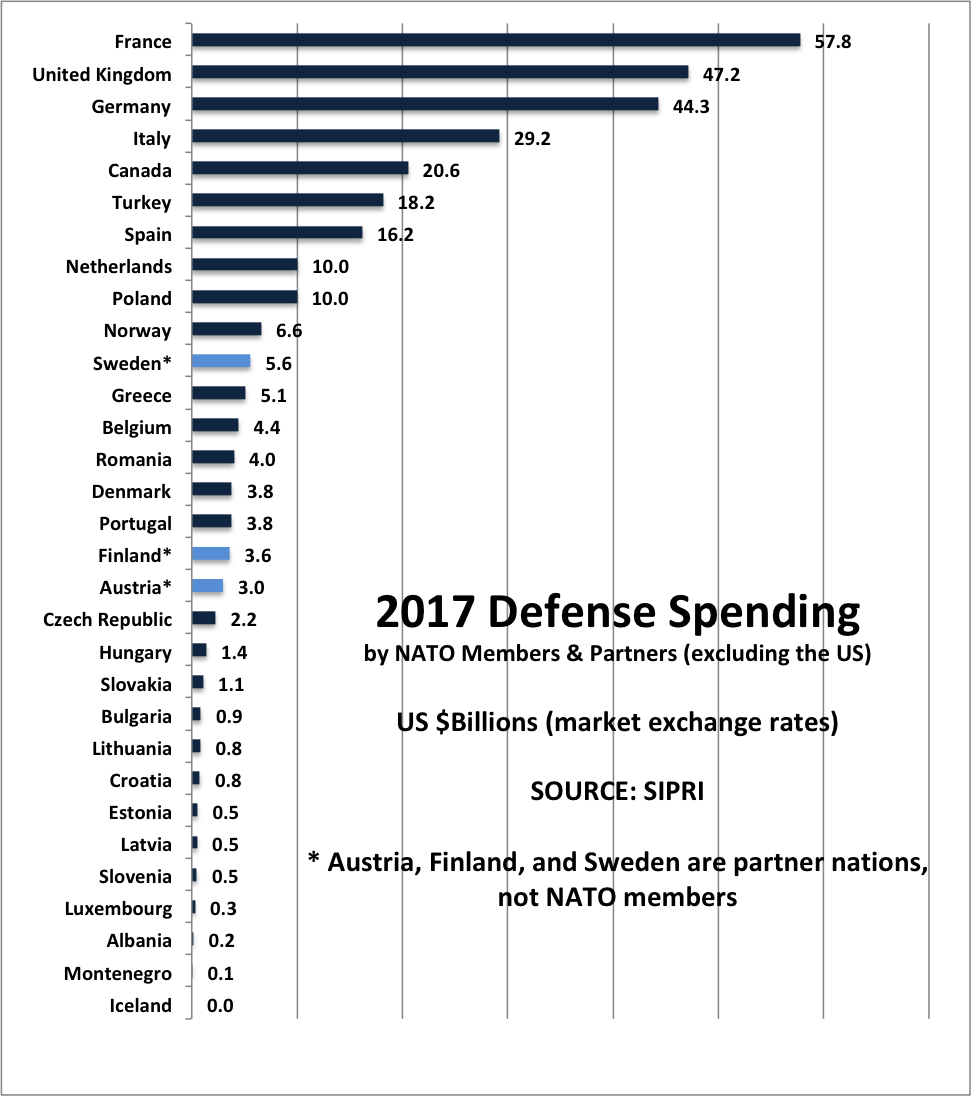

At the other end of the scale, ten NATO nations spent less than $1 billion on defense in 2017: Bulgaria spent almost $900 million, followed by Lithuania, Croatia, Estonia, Latvia, Slovenia, Luxembourg, Albania, Montenegro, and finally Iceland, which has no military and a military budget of $0. But Iceland serves the alliance as a strategically located base in the North Atlantic — not all contributions are monetary.

2. Most nations can’t pay much

“The sinews of war are infinite money” — Marcus Tullis Cicero

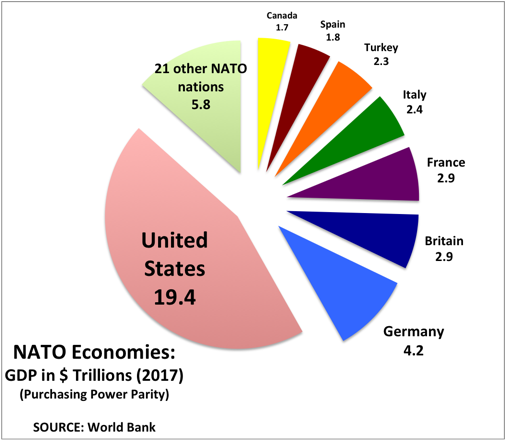

Strategists have long recognized that the basis of military power is economic power. Well, America’s economy is slightly larger than next seven NATO members combined. These same “Big Seven” non-US NATO nations — Germany at No. 1, followed by Britain, France, Italy, Turkey, Spain, and No. 7, Canada — just happen to be the seven biggest spenders on defense, although not quite in the same order. (France and Britain are the top spenders, while Turkey and Canada outspend Spain).

The other 21 members of NATO, mostly small and generally poor, collectively add up to barely over 13 percent of NATO’s combined GDP and just six percent of combined defense spending. So even if these nations doubled defense spending as a percentage of GDP, they wouldn’t have much impact on the alliance overall.

Yes, small nations can provide niche capabilities, such as special forces. Romanian anti-aircraft guns protect US Army units that largely disbanded their air defenses since 1991. But the raw power of the alliance depends almost entirely on the US and a handful of larger European nations.

3. Most nations spend on the wrong things

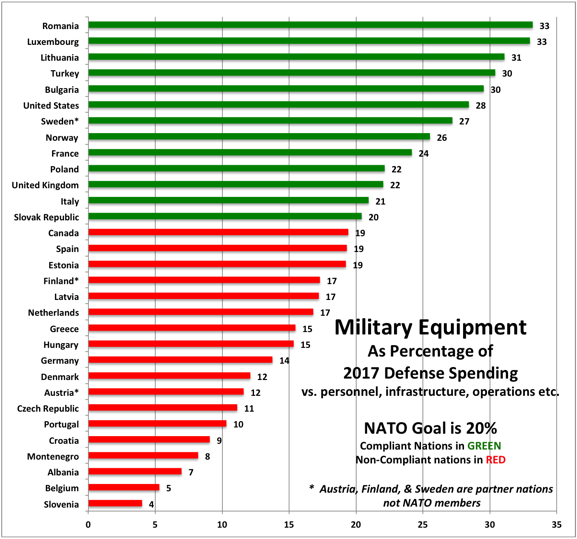

Not all defense spending produces the same amount of combat power. Every NATO member and major partner spends at least a third of its defense budget on people, for things such as salary, healthcare, and often retirement. Even the US spends 42 percent of its defense budget on personnel, and that’s not counting the entire Department of Veterans’ Affairs. Germany, Europe’s largest economy, spends 49 percent. For countries like Belgium, the figure exceeds 70 percent.

Conversely, most countries spend fairly little on actual weapons. NATO has a goal of spending of 20 percent of defense budgets on equipment (both procurement and R&D). Only 12 NATO members (plus partner Sweden) meet that target, in many cases because they’re desperately replacing decrepit Soviet-era equipment. Even then, none of them is over 33 percent. The US spends 28 percent, Germany spends just 14 percent.

4. Most nations are moving in the right direction

The bright spot in this discouraging data is that most NATO members, 22 out of 29 are increasing their defense spending. In fact, a slight majority, 15, are increasing defense spending faster than their economy is growing (measured by GDP PPP). That means they’re moving closer to that two percent goal. But with a few exceptions like Lithuania, where defense spending increased almost 1300 percent faster than GDP over the last five years, most of them are moving slowly.

America, The Giant

Just to give you one last look at how the US dominates NATO spending, here’s a graph that compares the size of countries’ economies (vertical axis) with the percentage of that economy they spend on defense (horizontal).

The US is way out in the far right corner, with by far the biggest economy and the highest percentage of defense spending. The rest of the NATO members are partners are clustered at the bottom left, with much smaller economies (so they’re towards the bottom) and much lower percentages spent on defense (so they’re towards the left).

In fact, on this scale, they cluster so close together it’s hard to make most of them out, which is why we have a second chart that omits the US and zooms in on everyone else so you can read the country names:

A Note On Methodology

We worked with CSIS, the Center for Strategic & International Studies, which recently published a study we highly recommend called Counting Dollars or Measuring Value, and combined their data with the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI) database on global defense spending and World Bank figures on Gross Domestic Product (GDP — specifically GDP PPP).

Whenever possible, we’re using GDP adjusted for Purchasing Power Parity, rather than the conventional market exchange rates. Why is that? Because all countries spend most of their defense budgets at home in local currency, primarily to pay their troops and civil servants.

If we converted to dollars at traditional market exchange rates, the rest of NATO would look even smaller alongside the US. But this metric really only reflects the ability to buy weapons on the world market, a small portion of most nations’ spending, so PPP is a better reflection of true buying power.

The exception here is SIPRI data: They didn’t have PPP-adjusted figures, so their statistics reflect the market exchange rate.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.