Build Bare-Bones Network & Small Satellites For Multi-Domain Battle

Posted on

Army ATACMS. The missile is being upgraded to hit enemy ships at sea.

WASHINGTON: The Navy wants the Army’s help win a future Multi-Domain Battle with China, a senior defense official told me last week, but to get it, the two services have to connect through a simple, robust network using small and rapidly-launched satellites.

Low-cost, quickly-launched Tactical Satellite under construction for the Operationally Responsive Space program.

We don’t need massive bandwidth to handle video teleconferences, full motion video from drones, PowerPoint briefings, and all the digital tools of “micromanagement,” the official believes. We just need a regional command-and-control network for voice commands and bare-bones-data – I’m here, the enemy’s there, shoot them not me – that can run off a single small satellite.

“It doesn’t have to be a big network,” he told me. “You could have one satellite…a temporary small satellite that you’ve popped up.”

This is in keeping with the early Concept of Operation developed for the Air Force’s Operationally Responsive Space program (although the official didn’t mention ORS by name). ORS seeks to end the US military’s dependence on highly capable, highly complex and highly expensive satellites. These multi-billion-dollar masterpieces would take months or years to replace if an adversary shot them down — as China demonstrated it could in 2007.

Chinese DF-15B Short-Ranged Ballistic Missile (SRBM) during PLA Rocket Force exercise.

Fighting Rockets With Rockets

Beijing invest heavily in land-based missiles, which 19 months ago were elevated to an independent branch of service, the PLA Rocket Force. (China’s development of mid-range missiles, notably, is not restricted by the Intermediate Nuclear Forces (INF) pact that binds the US and – on paper – Russia). China relies on land-based missiles against enemy aircraft, ships, and ground targets, a tactic known as Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD). The US could do the same from the Pacific’s many islands, many experts argue, rather than depend primarily on airbases and ships.

The Army could perform three key missions, the official said:

Adm. Harry Harris

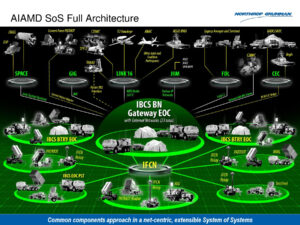

- Air & Missile Defense, protecting US air bases. The Army already plays a leading role here with its THAAD and Patriot batteries, but its fire control networks don’t connect to Navy ones. That’s something Pacific Command chief Adm. Harry Harris wants to fix.

- Land Attack, striking enemy launchers, sensors, and bases. Again, the Army already has some hardware for this role: the aging ATACMS missile, fired from HIMARS trucks and MLRS tracked launchers. The service is also developing a longer-ranged replacement, Long-Range Precision Fires – but LRPF’s range is still limited by the Intermediate Nuclear Forces treaty to under 500 kilometers.

- Anti-Ship, sinking enemy ships at sea. This is the Army’s newest mission (although the service ran coastal forts through World War II). The hardware is still in development under supervision of the Pentagon’s Strategic Capabilities Office: an anti-ship upgrade to ATACMS. The Army proposed this role as part of its Multi-Domain Battle concept, and Adm. Harris has eagerly embraced it.

“In all three (missions), they provide the same advantage, which is they have highly maneuverable, flexible units that are not fixed at a site like an airfield,” the official told me. “If I commanded a battalion of HIMARS, after I shot, the first thing I’d do is move, because if the enemy has overhead imagery (from satellites, spy planes, or drones), they’re going to be like, ‘Right there. Get on it.’ You want to be gone” before the retaliatory strike.

THAAD missile launch.

An airfield doesn’t have that option. “Let’s say I take off from my airbase to strike you,” he said. “Well, you can hit my airbase while I’m in the air. Now I’ve got to go to a new airbase – or, more likely, you took out all my munitions and fuel,” so even if the aircraft themselves survive, they’re tactically useless.

That said, the official went on, the services are working on ways to “maneuver” air bases. “Expeditionary airbases” could be set up and taken down in short order. “Cluster bases” would allow aircraft to play a shell game with the enemy by relocating repeatedly among a group of nearby airfields. This is a key reason the Marines bought the F-35B Joint Strike Fighter, so they could scatter the planes in the event of war and take off from a wide variety of locations.

Even so, an Army battery is always going to be more mobile and easier to hide than an airfield. Indeed, though the official didn’t say this, ground units would even have some advantages over ships. True, warships are always moving and they can move faster than ground units, and in the Pacific they have more room to maneuver. But ships are also large metal objects on a flat surface. HIMARS trucks are much smaller and can hide among radar-confusing clutter like buildings, trees, and rocks.

The important thing is that each arm of service has its unique advantages and disadvantages, the official said, so we want all of them working together. The American military’s distinctive strength since at least 1986 has been its ability to blend the branches into a single force. The Multi-Domain Battle concept has caught fire because it proposes to update jointness for a new era of simultaneous conflict on land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace.

But to fight together, the services need to talk to each other, which is where the network comes in – and it’s not easy.

US and German Army soldiers participate in a videoteleconference.

Unplug The Micromanagers

If units from different services aren’t on the same network, they can’t share data on where they’ve spotted the enemy. That lets targets escape. They also can’t share data on where friendly forces are. That can lead to lethal accidents.

‘The biggest part of this is getting the non-air defense stuff into Link-16 or a Common Operational Picture (COP),” the senior defense official said. “My son’s out on USS John Paul Jones…. I don’t want the Army firing out there unless I know they’re inside the Navy COP, because that missile, once it gets airborne, is looking for the first metal object nearby where it’s set to go. And if it’s USS John Paul Jones….” Well, the polite term is “fratricide.”

“So they have to be inside the COP, and that costs money,” the official went on. “The coms systems for Army HIMARS systems were built for talking to JTACs (Joint Tactical Air Controllers) and ground controllers on very specific Army frequencies that aren’t actually optimized for maritime (and) air combat….But they can get there.”

What matters about such a network is its reach, not its bandwidth. The services need to share basic data,

A simplified (yes, really) overview of the Army’s proposed IBCS command-and-control network for air and missile defense.

such as what friendly units and targets are at what coordinates, and plain-text orders, much like the telegraphic transmissions of old, augmented where needed with voice communications.

Such a bare-bones network is much easier to keep operating under attack. Complex features and large files, like video, give plenty of places for hackers to hide malicious code; plaintext doesn’t. High-bandwidth transmissions are easier to detect, triangulate, and jam; low-bandwidth ones can be brief bursts of data. Powerful communications satellites take billions of dollars and years of time to build, making them irreplaceable during a conflict; cheap mini-sats can be tossed into orbit by the handful.

Yes, you’d have to give up bandwidth-hungry features like full motion video, video teleconferencing, and PowerPoint slides, the official admits. But those are all luxuries we can dispense with in time of war, he argues – and we might fight better without the micromanagement they enable.

“We’ve done a lot of exercises recently where we cut bandwidth 80, 90 percent, and the video conferences go away…PowerPoint goes away,” the official says.

The USS John Paul Jones test-fires an SM-6 missile from a Vertical Launch System (VLS)

“We want coms where Washington can tell the captain of the ship what to do,” he adds. “We need coms where the captain of the ship can talk to the (Army HIMARS battery) and say, ‘here’s the picture I see – by the way, here’s where I am, appreciate you not hitting me’ – and then his system goes, ‘got it, I got you, I got the enemy, I can hit the enemy.’”

“One of the greatest things about the US military… is our O-5 commanders (mid-grade officers like lieutenant colonels and Navy commanders): COs of ships, commanders of squadrons, battalion commanders,” he told a recent briefing at the Center for Strategic & International Studies. “The US way of war is to delegate down to that level.”

“In the world of email and tight management, this skillset could go away,” he warned. “It’s going to be critical in future war, when there’ll be no email or false email or email that comes and goes. We have to preserve it in the face of an onslaught of micromanagement.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.