Boeing’s Block III Super Hornet ‘High End’ Complement To F-35: Stackley

Posted on

Boeing Advanced Super Hornet. The proposed Block III Super Hornet is similar.

NATIONAL HARBOR: Boeing’s proposed Block III upgrade to the Super Hornet would be a “fairly high-end” complement to the F-35C Joint Strike Fighter, acting Navy Secretary Sean Stackley believes. Instead of seeing Super Hornets as a potential replacement for the F-35 — as President Trump proposed — Stackley and other naval leaders at the Sea-Air-Space conference here repeatedly emphasized the two are not competitors, but are complementary. In fact, the Navy sees a role for both in high-intensity, high-tech, high-end warfare against the thick anti-aircraft defenses known as Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD).

Sean Stackley and aides with reporters at Sea-Air-Space.

It’s not a “high/low mix,” Stackley told reporters yesterday. “That’s too Air Force.” (The term “high/low mix” originally referred to the Air Force’s combination of twin-engine F-15s and single-engine F-16s). In particular, he said, “we’re looking at a Block III F-18. It’s fairly high-end. It doesn’t have all the stealth characteristics of a fifth-gen fighter, all the advanced capabilities of an F-35, but it’s an extremely capable aircraft.”

But, I asked, what can any Super Hornet model do that an F-35 can’t? “It has payload,” Stackley said at once. “The Super Hornet has a lot of payload, and that’s a good complement to the F-35, which has stealth and sensors.” (Of course, that Hornet payload can only be carried out of range of high-end Integrated Air Defenses while the F-35C penetrates and kills them.)

The F-35 can use its stealth to be “omnipresent,” slipping undetected into defended airspace, where it can use its advanced sensors to detect threats, weak points, and targets, said the incoming director of the F-35 Joint Program Office, Adm. Mat Winter. Then the F-35s transmit that data back to the rest of the force, from Navy Aegis destroyers to, yes, F-18s. Their wings loaded with more missiles than a stealth aircraft can carry in its internal bays, the Super Hornets can hang back at a (relatively) safe distance, yet use the targeting data the F-35s gathered at short range.

F-35C

Wait, I asked: F-35s have a special hard-to-intercept datalink, MADL, to share information among themselves without the transmission being detected, but they communicate to older aircraft like the Super Hornet on the standard NATO Link-16. Won’t the enemy pick up the Link-16 transmissions and triangulate their location? “It’s not a long phone call to your grandmother, it’s a burst,” Winter replied. By using their sensors to find blind spots in the enemy’s sensor arrays, by angling their transmissions away from hostile listeners, and above all by keeping messages short, he said, the F-35s can send data to the rest of the force without giving themselves away.

In this concept of operations, the synergy between F-18 and F-35 is a bit like the relationship between a sniper and his spotter. Sure, the spotter is armed, but his major contribution is to pick out targets for the guy with the really big gun. If you’re more historically inclined, imagine a late medieval knight going into battle with both longsword and mace. Like the F-35, the sword is best suited to slip through gaps in the enemy’s defense, but if you want to pound on someone as hard as possible, you need the mace, i.e. the F-18. Or think of a Dungeon & Dragons group where the F-35’s the thief, sneaking up behind the bad guys to deliver a devastating sneak attack, while the F-18’s the fighter whaling away on the front line. (In this nerdy analogy, the E-2D would be the wizard and the aircraft carrier itself the cleric, where the others go to repair/heal).

A Navy F-35C and a F/A-18E Super Hornet sit together on a runway.

Of course, the respective contractors don’t entirely agree with this division of labor. Lockheed Martin says the F-35 can carry just as many munitions as the Super Hornet can — about 18,000 pounds — if it carries some under the wings, just as the F-18 does. Of course, then the F-35 loses the smooth lines that make it stealthy. (Lockheed calls this “beast mode”).

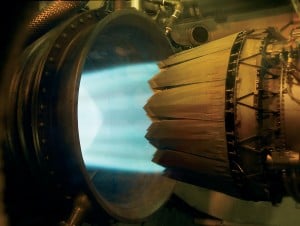

For their part, Boeing says their Block III upgrade to the Super Hornet will give it the latest datalinks and cockpit displays, as well as at least one unique sensor the F-35 lacks, a so-called InfraRed Search & Track (IRST) system they say can detect stealth aircraft by the heat of their engines, without relying on radar. (Lockheed says the F-35’s Distributed Aperture System includes excellent infrared sensors, good enough to track the Falcon 9 rocket from hundreds of miles away even after it turned its engine off).

F-35 engine (F-135) afterburner test

The Block III will also have built-in fuel tanks, said Boeing VP Dan Gillian, so the upgraded Super Hornet and the F-35 will have “comparable” range. (Exact ranges depend on weapons carried and are kept secret). These “conformal fuel tanks” are more aerodynamic than traditional drop tanks, making them not only more fuel-efficient but also more stealthy. However, Gillian told reporters at Sea-Air-Space, the current Block III package doesn’t include the stealth enhancements of Boeing’s earlier Advanced Super Hornet proposal, nor does it include an expensive new engine being worked on by GE.

It looks like Boeing deliberately trimmed Block III down to the must-have enhancements that can easily be inserted into the Navy’s existing F-18s when they next go in for overhaul. The Navy already plans to rebuild hundreds of its Super Hornets to extend their service life by a third, from 6,000 to 9,000 flight hours. “The first airplanes will hit six thousand hours early this year,” Gillian said. “It’ll start slow, (but) you get into the 20s, and we’ll see 60, 70 airplanes a year.” As long as the planes are in the shop, why not upgrade them to Block III standard for what he estimates as “a few million dollars”?

That rough estimate brings us to the bottom-line reason why the F-35 and F-18 are complementary: money. The carrier-capable F-35C variant currently costs $121.8 million, but Lockheed promises to get it down to $100 million. That’s compared to $70-odd million for a new Block III Super Hornet — which the Navy is still buying — or maybe $5 million to upgrade an old one.

The Navy doesn’t have enough fighters to equip its squadrons now, and it can’t afford to buy F-35Cs fast enough to fill the “fighter gap,” let alone to replace all its Super Hornets overnight. So, for decades to come, carrier air wings will be a mix of F-35s and F-18s: initially a 1:3 ratio of squadrons, later 2:2. The Marine Corps, by contrast, will go to an all-F-35B force on its amphibious ships, so the overall mix at sea will be more tilted towards the F-35 than the carrier group ratios suggest. That’s especially true in the Pacific, where Marine F-35Bs also operate from Japan and can rapidly deploy throughout the region.

“We have long planned on a mix of fourth and fifth generation squadrons comprising our air wings,” Stackley said. “They’ve always been complementary. They always have.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.