Birthing Ships is Never Easy; Give LCS A Break

Posted on

The chorus of criticism facing the first ships of the Navy’s new Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) class calls for a little historical context to be brought to this debate. Almost all new ship classes experienced considerable “birthing pains” in their early days.

The chorus of criticism facing the first ships of the Navy’s new Littoral Combat Ship (LCS) class calls for a little historical context to be brought to this debate. Almost all new ship classes experienced considerable “birthing pains” in their early days.

This is not new. Indeed, the first six frigates acquired by the American Navy in 1797 all came in late and over budget.

The most strident criticisms about LCS focus on the USS Freedom (LCS-1, built by Lockheed Martin) and Independence (LCS-2, built by General Dynamics and Austal), which in addition to being the firsts of their respective ship design types, are essentially research and development firsts-of-class ships –– virtual prototypes. This means that these ships are experimental with characteristics, issues and challenges that will be corrected in follow-on ships. The Navy contributed to this situation, describing the lead units of both variants as “Sea Frame 0” platforms, begging the question: “what’s a ‘Sea Frame,’ anyway?

All the first-of-class surface warships in recent Navy history have experienced significant problems to one degree or another, all of which generated considerable criticism at the time of their construction and initial deployment.

The Knox class frigates (which achieved Initial Operational Capability in 1969) were labeled as “McNamara’s Folly” after then-Defense Secretary Robert McNamara and were often criticized for their single screw, single gun, and design-to-cost approach. Originally designated as destroyer-escorts, the entire class was re-classified as frigates in 1975 (in a general re-classification of U.S. surface warships), but were forever compared unfavorably to “real” destroyers.

Spruance class destroyers (IOC 1975) were criticized as bit 7,900 ton “destroyers” possessing only two five-inch guns and an ASROC launcher. They were hardly more capable than the still-in service World War II-era destroyers upgraded as part of the Fleet Rehabilitation and Modernization (FRAM) program. But the ships’ critics conveniently ignored other key facts that the Spruance-class was also helicopter capable, equipped with NATO Sea Sparrow Self Defense Missiles, and boasted a powerful bow mounted sonar. At the time, criticism of the Spruance ships was loud, strident and frequent.

The Perry class frigates (IOC 1977), much admired by many LCS critics, were unfavorably branded by as “square pegs” when they were first deployed. Criticism of the Perrys was fierce, including such charges as the ships had only a single shaft and were not survivable and suffered from the lack of main propulsion redundancy; they were problem-prone and had unreliable ship’s service diesel generators; a power-limited “fish finder” high-frequency sonar; and the Oto Malera 76mm was derided as a “pop gun” rather than a “proper” 5-inch gun. On top of all that, the critics said and the crew was too small and was unable to operate and maintain the ships properly. These echo many of today’s criticisms of LCS.

The Ticonderoga class cruisers fared little better when the lead ship first deployed in December 1983. Gallons of ink were spilled about how top heavy the ships were. They had weight and moment restrictions, suffered from poor sea keeping characteristics, and had unreliable “hydraulic fluid rain forest” MK26 missile launchers.

The Arleigh Burke class guided missile destroyers didn’t face as much criticism as its predecessors, but it was still roundly derided for having only a helicopter “lily pad” without an onboard hangar. Its engineering spaces with their low overheads bulged with pipes and cables. It was also said that the first ship, Arleigh Burke, was rebuilt three times over before final delivery because of an immature design, problems with sharing software between shipyards, and the late addition of “stealth” features.

Despite the early criticisms of almost every recent surface warship firsts of class, the Navy was able to successfully address the initial criticisms and fix their shortcomings. The criticisms of the Perry class ships were overcome in time, especially after the upgraded Coherent Receiver/Transmitter (CORT) combat systems were introduced.

The Spruance class evolved into a first rate anti-submarine warfare platform, with the Navy augmenting the original SQS-53 bow-mounted sonar with towed acoustic arrays in several ships of the class. Intelligence collection spaces were added aboard several ships, and the addition of Tomahawk cruise missiles, weapons that revolutionized the surface Navy by giving it a robust land attack warfare capability, were added later on. The four Kidd variants embarked improved MK26 launchers. Their design was the basis for the Ticonderoga guided missile cruisers.

The Ticonderoga class evolved into the premier anti-aircraft warfare platform in the world, and they too were fitted out with the MK41 vertical launching systems (VLS) to replace the MK26 missile launchers when VLS matured. In 2013, select ships have been upgraded to capable ballistic missile defense (BMD) assets. And what about the Arleigh Burke destroyers? Not only were later Flight II versions outfitted with helicopter hangars, but they have evolved into what many naval experts say are the most capable surface warships ever built, capable of integrated AAW, ASW, BDM, and strike warfare missions.

Given the Navy’s history of initial issues and challenges, which the first ship of almost every modern surface combatant class has faced, are the challenges confronting USS Freedom and Independence significantly different? While it of course would be ideal if the first ships of any warship class would be delivered ready to go to war. It would be nice, but why should we expect less of the LCS firsts-of-class than the Spruance, Perry, Ticos, and Burkes have all achieved over time?

While some first-of-class ships are more highly criticized than others, the extent of negativity seems mostly attributable to the degree or amount of “newness” inherent in the ship’s design. The more “newness” that exists, the greater is the level of criticism. With LCS, which uniformed and civilian Navy leaders have universally said will usher in a new era in terms of how the Navy will conduct overseas presence and engagement, that “newness factor” is high. The Ticonderoga and Burke classes fared better, in terms of the overall level of criticism, compared to that leveled at lead ships of the Knox, Perry and Spruance classes, and now Freedom and Independence.

Part of this is attributable to the fact that Ticonderoga evolved from the already understood Spruance class, taking advantage of the same hull design and propulsion plant, but adding a new combat system. The Burke evolved from the Ticonderoga with the same combat system and propulsion plant, but a different hull design.

However, the Perry FFG began as a blank sheet of paper––originally conceived as a “Patrol Frigate” (PF-109)––with a significant amount of “newness”: new hull , new engineering plant, new sonar, new gun, and a new minimal-manning crew concept.

The LCS firsts-of-class are similarly “highly new”: new hull designs, new requirement for high speed, modular mission packages, heavy reliance on off-board vehicles for sensing and scouting, very minimal manning, crew swap, new shipbuilders, and a contractor supported maintenance strategy. Moreover, the Freedom and Indepedence are replacing three classes in terms of numbers, if not precisely in mission requirements: Cyclone class PCs, Perry class FFGs, and Avenger class MCMs. Given this degree of “newness,” it should not be surprising that LCS has generated so much public turbulence in the early stages of the programs.

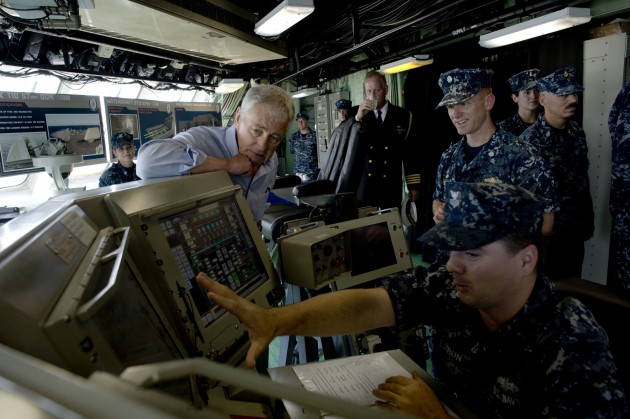

The level of criticism being directed at LCS will most likely continue until additional ships of both the Freedom and Independence classes are delivered and deployed. Key to all this will be the fact that officers and sailors will learn in minute detail how to operate and maintain them––and unlock the operational flexibility and adaptability that Navy officials maintain are inherent in their respective designs.

Recent Navy history vividly demonstrates that the first ship of every class faced obstacles. We should maintain perspective: every new class of warship debuts to a chorus of critics

Robert Holzer, senior national security manager at Gryphon Technologies, was director of outreach for the Pentagon’s Office of Force Transformation and the longtime naval correspondent for Defense News. He is not working on LCS for any of the companies building the ships.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.