Beyond INF: Countering Russia, Countering China (Analysis)

Posted on

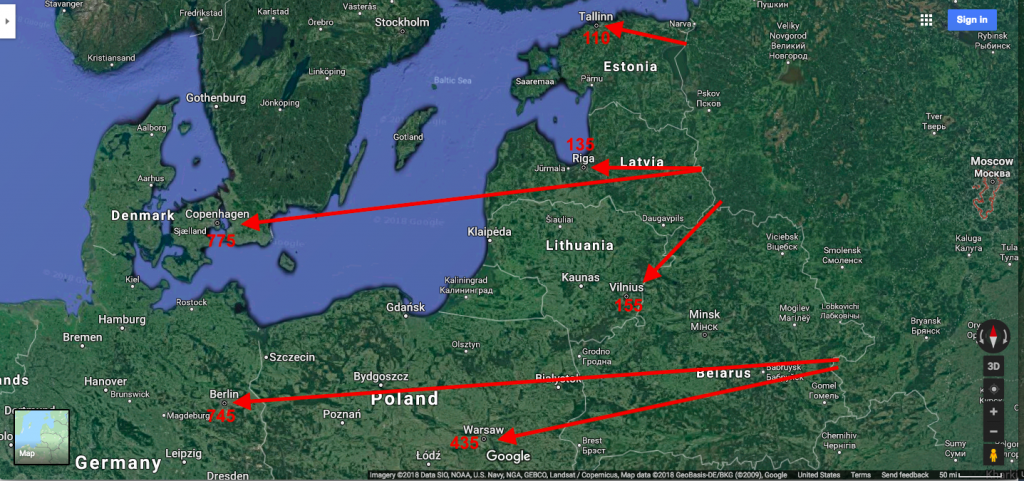

Approximate ranges in miles between western Russia and select NATO capitals. (Note ranges are much shorter from the Russian enclave of Kaliningrad; see below). SOURCE: Google Maps

WASHINGTON: What long-range weapons should the Army buy if President Trump keeps his promise to end the 1987 INF Treaty? The Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces accord, despite its name, bans all ground-launched cruise and ballistic missiles, nuclear or not, with ranges between 310 and 3,400 miles. So withdrawing from INF would open up a lot of options — but which is best?

It turns out that what you want to build depends on what you want to kill and from how far away. That means the US needs a mix of missiles for different missions — and it needs a different mix for a naval war in the vast Pacific against China than a land war in Europe against Russia.

“Long-range precision fires, that’s our No. 1 priority,” Army Secretary Mark Esper said last week. “(They) would provide us the capability (to) either, for example, support the Air Force by suppressing enemy air defenses at hundreds upon hundreds of miles or support the Navy by engaging enemy surface ships at great distances as well.”

Army Secretary Mark Esper speaks to soldiers at the National Training Center on Fort Irwin, California

“That is critical to multi-domain operations,” Esper added. That’s the rapidly evolving interservice concept for defeating advanced adversaries with relentless, coordinated attacks from all five domains of warfare: land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace.

But Esper’s examples are two distinctly different missions, each most relevant to a different theater of war.

“The National Defense Strategy is really clear,” said David Johnson, a former top advisor to the Army Chief of Staff who’s now with RAND. “The problem in Europe is a very competent adversary that’s right on the border…. That problem is radically different than hitting command and control complexes in the Pacific or adversary navies.”

Withdrawing from INF as at least as much about countering China — whose massive arsenal of intermediate-range missiles was never covered by the treaty — as it is about Russia. But, as Johnson and other experts pointed out in interviews, both ranges and targets are very different in the Pacific than in Europe:

- The European theater is mostly land, less than a thousand miles across from Moscow to Berlin. Russia can deny the skies to NATO with ground-based anti-aircraft missiles and radars on their own territory, which would the primary target for US weapons.

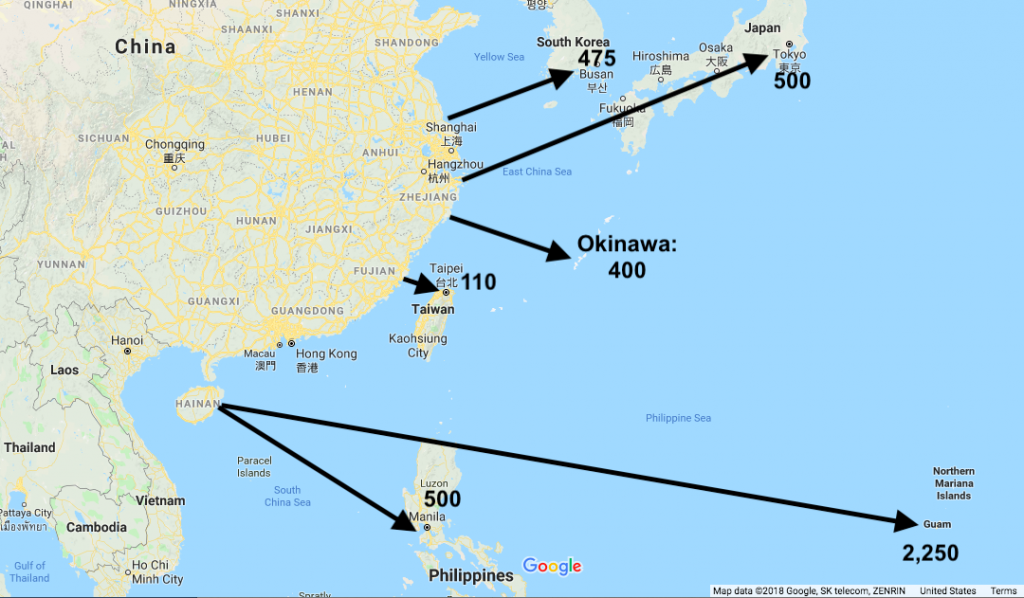

- The Pacific theater is overwhelmingly water, 2,250 miles wide from the US base on Guam to the Chinese base on Hainan. China can blitz US airbases in Okinawa, mainland Japan, and Korea with its own land-based missiles, but to establish its own control, China needs to send forth warships — a very different type of target.

Different missions require different technologies — the most mature of which are banned by INF. “If and when the INF treaty is lifted,” Esper said at the American Enterprise Institute on Thursday, “what that does is enable us… to do that same type of mission in a conventional way.”

The traditional weapons Esper is referring to are ballistic missiles, which are blindingly fast but follow fixed courses, and cruise missiles, which are slower but more maneuverable. Both types arose from the Nazi V-weapons of World War II, both are widely used around the world, and both are covered by INF.

By contrast, hypersonic missiles have the potential for both speed and agility, and the 1987 INF treaty didn’t mention them because they didn’t exist then — but they remain experimental even today. Even more exotic, though less cutting-edge, is the Army’s idea of a Strategic Long-Range Cannon that launches missiles with gunpowder rather than rocket boosters, similar to the Nazis’ never-finished V-3.

So which of these weapons would work best against what targets in what theaters? To answer, we need to understand the basics of how they work.

Approximate ranges in miles from Chinese territory to select US and allied targets. SOURCE: Google Maps

Treaty Vs. Technology

The INF treaty is the reason the US military today has no ground-launched missiles between the Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS), with a range of 186 miles, and the Air Force’s Minuteman III Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM), with a range of over 6,000.

The Air Force’s BGM-109G Ground-Launched Cruise Missile (GLCM) was a Navy BGM-109A Tomahawk modified to fire from a Transporter-Erector-Launcher (TEL) truck.

However, the Navy’s mainstay cruise missile, the Tomahawk with its 1,000-mile range, could easily be fired from land. In fact, in the 1980s, the US repurposed the Tomahawk as the truck-mounted Ground-Launched Cruise Missile (GLCM), later banned by INF. Today, the Aegis Ashore missile defense sites in Poland and Romania are basically shipborne missile systems without the ship, requiring at most modest upgrades to launch Tomahawks.

But while Tomahawk is the easiest option, it’s not necessarily the best. Introduced in 1984, it might struggle to penetrate a modern anti-aircraft defense like Russia’s or China’s. “Cruise” missile means it flies through the air like a jet, so it can therefore be detected and shot down like one — especially since Tomahawk is both fairly easy to see on radar (i.e. not stealthy) and relatively slow, at about 550 miles per hour. What’s more, unlike the truck-borne GLCM of the 1980s, the Aegis Ashore silos are static, making them impossible to hide from a preemptive strike.

If the US wanted a new mobile, land-based cruise missile, it might do better to adapt the JASSM-ER used recently in Syria, said Tom Spoehr, a retired Army three-star now with the Heritage Foundation. The Joint Air-To-Surface Standoff Missile – Extended Range can fire about 600 miles. That’s less than the Tomahawk, but more than adequate for most European missions and, in the Pacific, enough to hit mainland China from launch sites in the Philippines. What’s more, unlike Tomahawk, the JASSM family is designed to evade modern radar.

There’s even an anti-ship variant, the Long-Range Anti-Ship Missile (LRASM), although to kill these larger targets require a larger warhead that reduces range.

How about speed? Exact specs for the JASSM/JASSM-ER/LRASM family are, unsurprisingly, classified, but it’s definitely subsonic — in other words, slower than the speed of sound, about 760 mph at sea level. Supersonic cruise missiles do exist, such as the Russo-Indian Brahmos, but the US doesn’t have any. And in war, speed kills, because faster missiles are not only harder to shoot down but give mobile targets less time to hide.

One family of faster weapons is the Standard Missile series, built by Raytheon for the Navy. Fast and agile because they were developed to shoot down incoming aircraft and cruise missiles, Standard variants have evolved to kill ballistic missiles (SM-3) and even warships (SM-6). Tom Karako, head of the missile defense program at CSIS, proposes a hybrid of the SM-6’s multipurpose seeker and the SM-3’s 1,350-mile-range booster that could strike targets ashore, launched from either ships or land with tremendous speed.

The traditional solution for high speed, however, is the ballistic missile. Ballistic missiles are blisteringly fast, with speeds around 15,000 mph, about Mach 20. But their rocket boosters produce tremendous heat, making launches detectable by satellite. Once the rockets burn out, the reentry vehicle carrying the warhead can no longer maneuver, instead following a predictable parabolic (ballistic) course.

Ballistic missiles are still much harder than cruise missiles to shoot down, requiring specialized sensors and interceptors rather than standard anti-aircraft systems, but both the US and Russia have invested heavily in anti-ballistic missile defense. To defeat these defenses, a recently leaked Pentagon study suggests modifying a traditional ballistic missile with a Trajectory Shaping Vehicle (TSV): an advanced reentry vehicle that can maneuver unpredictably as it carries the warhead to the target.

But the Pentagon’s R&D chief, Mike Griffin, has made his top priority a more radical solution: hypersonics. The term simply means “faster than Mach 5,” but it usually refers to a so-called boost-glide vehicle that skips in and out of the atmosphere like a stone across a pond. Neither ballistic nor cruise, these hypersonic weapons would be slower than ballistic missiles, but faster than cruise missiles, and also highly maneuverable. That combination could help hypersonics both penetrate advanced anti-missile defenses — which both Russia and China possess — and hit moving targets at extreme ranges before they can relocate — a particular problem in the vast Pacific.

The problem with all these high-speed options is that, unlike subsonic cruise missiles, the US doesn’t have them today. A modified Standard Missile might require relatively little development time, which is why CSIS’s Karako favors it, but hypersonics remain experimental.

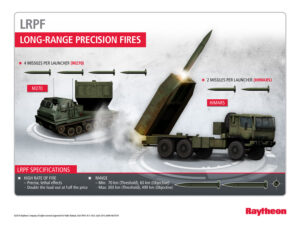

Ballistic missiles, by contrast, are old tech, but the US doesn’t have the right kinds anymore. With a 6,000-mile range, an intercontinental Minuteman III would be overkill for even most Pacific missions — not to mention the potential the enemy would mistake it for a nuke. The US destroyed its last intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM), the Army’s Pershing II, in accordance with the INF Treaty. The Army is now developing a new ballistic Precision Strike Missile. While the PRSM design is currently constrained to 310 miles by the INF, the Army has said increasing the range would be straightforward.

Approximate ranges in miles between the Russian enclave in Kaliningrad and select NATO capitals. SOURCE: Google Maps

Europe vs. Pacific

So which missiles should the Army build for which mission?

“There’s much more lucrative targets to be found in the Pacific with Chinese vessels,” Heritage’s Spoehr told me. “In Europe….I don’t see the high-value target.”

Land-based missiles deployed at “Expeditionary Advance Bases” could form a virtual wall against Chinese aggression (CSBA graphic)

The vast distances of the Pacific require speed and range, whose cost limits the number the US can afford — but the primary targets would be Chinese warships, which are expensive too. While larger than the US fleet, the Chinese navy is heavy on coastal patrol craft and light on larger vessels, both the seagoing warships required to secure its oil imports from Mideast and the amphibious transports required to seize disputed islands or Taiwan. All told, the Chinese power-projection fleet is about 151 high-value targets — one aircraft carrier, 23 destroyers, 52 frigates, 23 corvettes, and 52 amphibious ships of various sizes, by the Pentagon’s 2016 estimate — that could justify building several hundred long-range, high-speed, high-cost missiles: souped-up SM-6s, a new ballistic missile like PRSM, and/or hypersonic boost-glide vehicles.

By contrast, Russian troops can just get in their vehicles and drive to NATO territory. That presents a much larger number of individually much less valuable targets: thousands of missile launchers, command vehicles, battle tanks, troop carriers, supply trucks, and more, many of them by necessity within a few hundred miles of the front line. Killing them would require less powerful, shorter-ranged, and therefore less expensive missiles, which would be easier to afford in the huge numbers required. In the near term, that means ground-launched versions of current cruise missiles: JASSM-ER for well-defended targets within 600 miles, Tomahawks for lighter defenses and longer ranges. In the longer term, these would be joined by the Army’s ballistic PRSM and perhaps by projectiles from the proposed Strategic Long-Range Cannon.

Raytheon’s proposal for the new Precision Strike Missile (PRSM), formerly the Long-Range Precision Fires (LRPF) weapon.

There would certainly be overlap between the two theaters’ missile forces. The primary targets in Europe, and important secondary ones in the Pacific, would be the enemy’s air-defense systems. While the Army has argued it needs hypersonics to hit a small number of the hardest targets, such as buried bunkers, it envisions using a larger number of less exquisite weapons to hit the larger numbers of more vulnerable targets on the surface: radars, missile launchers, and mobile command posts.

Decimate these air defenses, and the non-stealthy aircraft that make up the vast majority of US and allied air power can strike at will. That’s crucial because land-based missiles aren’t the best solution to all military problems. If US aircraft can loiter over hostile territory, they can get right on top of targets and hit them with short-range missiles or even ordinary “gravity” bombs. Those munitions are both more responsive and less expensive than land-based missiles that must cover long distances to reach their targets — a particularly acute problem in the Pacific.

“In the Pacific, (land-based) missiles would need to have much longer ranges than weapons postured in Europe,” said Mark Gunzinger of the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments. “As a result, they would have to be larger and probably quite a bit more expensive — perhaps to the point that they would not be useful in very large numbers, relative to bomber aircraft that can carry large payloads of less expensive standoff weapons.”

By contrast, “the Baltic states and much of Poland are covered by Russian long-range strategic SAMs (Surface-to-Air Missiles): S-300s, S-400s, and in the future S-500s,” Gunzinger said. “A future US Army equipped with long-range precision fires — greater than 500 km range — could play a major role in suppressing Russians IADS (Integrated Air Defense Systems), enabling NATO air forces to penetrate.”

Once the US and its allies command the skies, they’re well on their way to winning the war on the ground — but in this new era of warfare, ground forces may have to blast a path through the skies for the air forces to follow.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.