‘Be Ready To Fight Now’: Top Admiral On Russia & China

Posted on

A Chinese destroyer, the Lanzhou, pulls in front of the destroyer USS Decatur in the South China Sea. China claims much of the sea and the resources below, but an international tribunal and every other country have rejected the Chinese claim.

WASHINGTON: The Navy’s top surface warfare officer called for his crews to rapidly develop “a sense of urgency” about the Russian and Chinese navies.

For the first time since the Cold War, Vice Adm. Richard Brown told the Surface Navy Association conference here, sailors must make ready for aggressive sailing by adversaries that come so close they scrape your paint, as a Chinese destroyer came within yards of doing last fall in the disputed South China Sea. And for the first time since World War II, junior sailors may have to pick up the pieces when their superiors are cut off or killed outright by a sophisticated surprise attack.

It’s a far cry from the past quarter-century of American dominance. A generation of naval officers have spent their entire career without worrying about an adversary hacking or jamming their communications, let alone sinking their ships.

The next big war, Brown said, could all too easily resemble the bloody early years of the Pacific campaign against Japan, whose superior skill and ferocious zeal often overcame US advantages in technology.

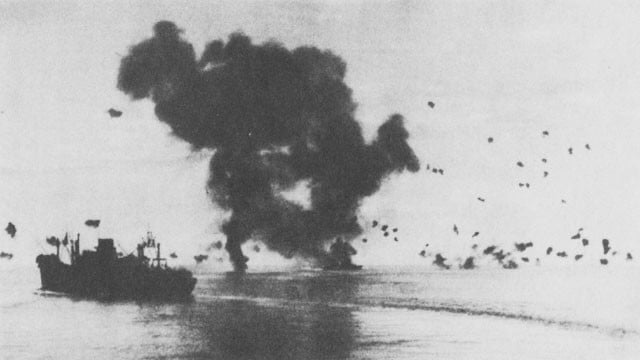

“You know, the Battle of Guadalcanal was a brutal campaign, but shows us what the next fight could be like,” Brown told an audience of naval officers and industry executives. “The naval engagements went something like this: usually at one or two in the morning, a sailor, either Japanese or American, saw a silhouette on the horizon, the search lights came on, and the opening salvos of 5- to 16-inch shells began slamming into ships at an average range of 3400 yards. Usually, the CO (skipper), XO (executive officer) and senior officers – even admirals – were killed immediately – but what happened?”

“Quartermaster[s] 3rd [class] took command of pilot houses and kept the ships in formation, engineers kept steam to the main engines and the screws turning, damage control teams kept the ships afloat, and ensigns and JGs (lieutenants, junior grade) put their gun mounts in local control and continued firing – continued firing – and we won.”

What’s essential, Brown said, is that even junior sailors learn to take initiative, rather than wait for admirals like him to tell them what to do in a crisis. The military term of art is “mission command,” where superiors set clear objectives — the why we’re fighting — but leave plenty of latitude on how to reach them — the how — and teach subordinates to take the initiative and improvise when the plan fails to survive first contact with the enemy.

“Most importantly, we must prepare for this great power competition by embracing the concept of Mission Command,” Brown said. “Mission command requires innovation and creativity, experimentation and rapid learning,…. While we need to deliberately plan for large-scale fleet engagements– and we’re doing that — emphasizing mission command will prepare our commanders to react to an environment rife with the fog of war, loss of communications, and imperfect information, while still executing commander’s intent.”

Now, initiative and improvisation have historically been a US strength, the admiral said. “The reason the U.S. Navy does so well in wartime is that war is chaos, and the U.S. Navy practices chaos on a daily basis,” a (probably apocryphal) Axis officer snarked in World War II, while a (probably equally apocryphal) Soviet lamented, “A serious problem in planning against American doctrine is that the Americans do not read their manuals, nor do they feel any obligation to follow their doctrine.”

But decades of uncontested dominance, increasing bureaucracy, and centralized, computerized command, control, & communications networks have taught many naval, air, and ground officers to keep their heads down and do what they’re told. In a failure-phobic culture, it’s better to face certain failure that can be blamed on someone else than to take a risk on your own head that might end your career. In the Navy, that culture contributed to Pacific commanders struggling without complaint to keep up a grueling patrol schedule until exhausted, under-trained crews caused two lethal ship collisions last year.

Wake Up & Smell The Competition

After the fall of the Soviet Union, Vice Adm. Brown said, “by the mere fact that the United States Navy woke up in the morning, we had sea control.” But that’s no longer the case, as US ships are routinely shadowed by modern Russian and Chinese ships in both the Atlantic and Pacific, and those rising rival powers pump more money and research into developing longer range standoff weapons and establishing footholds in the Arctic, the Middle East, Africa, and South America.

Brown took a look back to his life as a young sailor in the 1980s, when US and Russian ships regularly chased one another down and “traded paint” by bumping hulls. In those days, each deployment required “having your sea bag packed every time you got underway – you just might keep heading east or west…The lesson we learned during the Cold War was that we had to be ready to fight now.”

The days of that kind of competition are back, but it is severely straining the Navy’s ability to train crews and keep ships moving out on rapid-fire deployments. Ships have been skipping maintenance availabilities, and cutting repair and training rotations short in order to meet operational needs.

The Navy blamed the accidents that killed 17 sailors aboard the USS John S. McCain and USS Fitzgerald in 2017 on just such issues. A secret report written just days after the accidents and obtained by Navy Times outlines a shocking number of deficiencies, including radar systems that didn’t work, sailors who didn’t know how to use critical technologies, and a culture of distrust between sailors on the bridge and in the combat information center that led them to ignore one another while underway.

Damage to the destroyer USS Fitzgerald after its collision with a merchant ship.

Finding ways to train sailors faster and more comprehensively is a major part of the Navy’s plan for the future, though specifics have remained vague. The service has also been on the leading edge of developing new concepts to combat a rising China, with the Navy Air-Sea Battle effort raising issues latter tackled by joint doctrine and even the Army-Air Force Multi-Domain Operations concept.

Again, World War II — or rather the generation spent preparing for it — is a model. “We can do no better than to look to the legacy of the 1930s,” Brown said. “This was an era where fleet exercises, backed up by rigorous intellectual work at the Naval War College, created and refined concepts that ultimately helped win the war. Now is our time to do these hard things. It is our time to begin aggressive experimentation again in surface warfare.”

Brown’s plan is to lean heavily on the three-year-old Surface & Mine Warfare Development Center, which runs a kind of Top Gun for surface ship officers, and his even newer Surface Development Squadron, which is being tasked with experimenting with the ways the existing fleet can integrate small, medium and large unmanned surface vessels. That requires exploring questions over who owns those ships, who controls them, and how they’re integrated into the manned fleet and aircraft, all of which have yet to be worked out.

Experimenting with unmanned systems is “where you try stuff and you break it,” Rear Adm. Ronald Boxall, director of the surface fleet said Tuesday.

Overall, however, Brown said the Navy’s time is short, and ships will need to perform even more tasks in the future in more places as the pacing threats from China and Russia continue to evolve.

“We must learn more rapidly, we must innovate faster,” he said.

For the ship crews, “we need to have them prepared on a moment’s notice to turn the readiness we are building into lethality,” Brown said. “Lethality,” Pentagon cognoscenti will recall, was a favorite word of former Defense Secretary Jim Mattis.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.