Army Will Field 100 Km Cannon, 500 Km Missiles: LRPF CFT

Posted on

Army HIMARS trucks launch GMLRS (Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System) missiles

Within five years, the US Army will field new artillery weapons — howitzer shells, rockets, and missiles — with ranges of 70 to 500 kilometers, double that of current systems. After 15 years of close-range combat against insurgents, the service’s top priority is now what it calls Long-Range Precision Fires to counter “peer competitors” like Russia and China on vastly larger battlefields.

Brig. Gen. Stephen Maranian

“We were in a different fight. (Now) we’ve got to be ready to fight large-scale combat operations,” Brig. Gen. Steve Maranian, head of the Army’s LRPF Cross Functional Team, told me in an interview. “We’re looking at how we can increase the range, the volume of fire, and the lethality of our surface to surface fires…in the close fight with cannon artillery, in the deeper fight with our rockets and missiles, and then exploring what’s in the art of the possible at strategic ranges (where) the Army hasn’t had a surface to surface capability in several decades since Pershing.”

The Pershing II was an intensely controversial Cold War weapon that could nuke Moscow from launch sites in Germany. Today’s Army isn’t thinking of nuclear warheads — an atomic blast is pretty much the opposite of precise — but of precision-guided conventional weapons with Pershing-like range.

That’s a combination already found in many Chinese missiles, since Beijing is not a party to the Intermediate Nuclear Forces treaty, and in some Russian ones as well, since Moscow is almost certainly violating the INF. Maranian and other Army officials insist the longest range weapon in their plan — the PRSM missile, formerly known as LRPF — will go no more than 499 km, just short of the treaty limit of 500. But should the US withdraw from the INF treaty, the technology is certainly available to go farther.

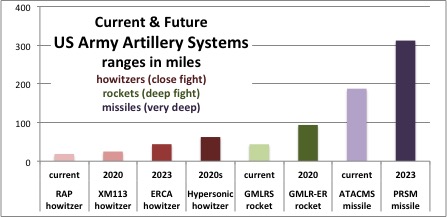

RAP: Rocket Assisted Projectile. ERCA: Extended Range Cannon Artillery. GMLRS: Guided Multiple-Launch Rocket System. ATACMS: Army Tactical Missile System. PRSM: Precision Strike Missile.

SOURCE: US Army.

Multi-Domain Battle

The Army’s plan is not just to trade salvos of missiles from a distance, but to combine its long-range artillery with other combat arms in what it calls a multi-domain battle.

As Maranian and his counterpart for aviation, Brig. Gen. Wally Rugen, explained to me in interviews, long-range artillery will have a symbiotic relationship with airpower. Drones will find targets for the artillery, artillery will destroy enemy anti-aircraft systems, and manned aircraft will strike deep through the resulting weak points.

Air & Missile Defense: Army Indirect Fire Protection Capability (IFPC) Multi-Mission Launcher (MML) test-fires an AIM-9X missile.

Artillery will also be symbiotic with air and missile defense, Maranian said: “We provide offensive fires, they provide defensive fires.” The artillery will take out enemy aircraft and missiles on the ground — “left of launch” — so the air defenders aren’t overwhelmed by too many incoming threats to shoot down. The air defenders will stop the aircraft and missiles that do launch before they can destroy the Army’s artillery batteries. (It’s even possible that Hyper Velocity Projectiles now in testing could turn regular howitzers into dual-purpose offensive and missile defense weapons).

The artillery will also get targeting data from ground vehicles and foot troops, Maranian said, and provide them supporting fire in return.

In order to move all this data from sensors and spotters across the force to the artillery’s shooters, over long distances despite enemy jamming and hacking, Maranian’s Cross-Functional Team is working particularly closely with Maj. Gen. Pete Gallagher’s CFT for the Army network: “I was just on the phone with (Gallagher) right before we called you,” Maranian said.

In fact, all eight Cross Functional Teams coordinate with each other in weekly video-teleconferences. But the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. Mark Milley, has made very clear that Long Range Precision Fires is the top priority of them all.

Why? Partly that’s because artillery was so badly neglected during the counterinsurgency era, to the point that a 2008 essay by three artillery officers called it a “dead branch walking.” Partly artillery is the top priority because the Army believes it can no longer rely on airpower.

Tracked variant of the Russian Pantsir S1 anti-aircraft missile system (NATO reporting name SA-22 Greyhound)

In Afghanistan and Iraq, fighter jets and B-1 bombers routinely came to the aid of ambushed ground troops. The anti-aircraft threat from the Taliban, al-Qaeda, and Islamic State was a handful of shoulder-fired missiles (Man-Portable Air Defense Systems or MANPADS) and lots of machineguns with only human eyeballs to guide them. Russia and China, by contrast, have advanced fighter aircraft, huge numbers of anti-aircraft missiles large and small, and automatic cannon, all coordinated by computer networks and guided by sophisticated radars that may even be able to detect US stealth aircraft.

Such defense complexes were originally called Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD), but the US military increasingly disparages the term, saying it will gain access and it won’t be denied. The Air Force, Navy, and Marines are all working on ways to crack open A2/AD, which we’ve covered extensively.

The Army is certainly hoping the other services can get their aircraft in, but it isn’t counting on it. Instead of the old reliance on airpower alone, the Army is now looking to coordinate attacks in multiple domains at once — not just on land but in the air, sea, space, and cyberspace. It will do so not just in order to support its own troops on the ground, but to destroy air defenses on behalf of Air Force, Navy, and Marine Corps aircraft, and even to sink ships at sea. This vision of multi-domain battle, however, depends on reviving and modernizing the artillery.

An Army M777 howitzer modified with an extra-long barrel for an Extended Range Cannon Artillery (ERCA) test.

Howitzers, Rockets, & Missiles

Different kinds of combat call for different weapons. Rather than invest in a single Long-Range Precision Fires system to rule them all, the Army is modernizing three,some under existing programs of record and some under Brig. Gen. Maranian’s CFT:

- 155 cannon, the cheapest option, for the close fight against the enemy’s frontline forces;

- guided rockets for the deep fight against enemy reinforcements and supply lines; and

- missiles, the most expensive munitions, for very deep or even strategic strikes against targets in the enemy rear and homeland.

Cannon shells have advanced dramatically in recent decades, with precision-guided Excalibur rounds and Rocket Assisted Projectiles to boost range. The current RAP fired from the current 155 mm howitzer can hit targets about 30 km (19 miles) away.

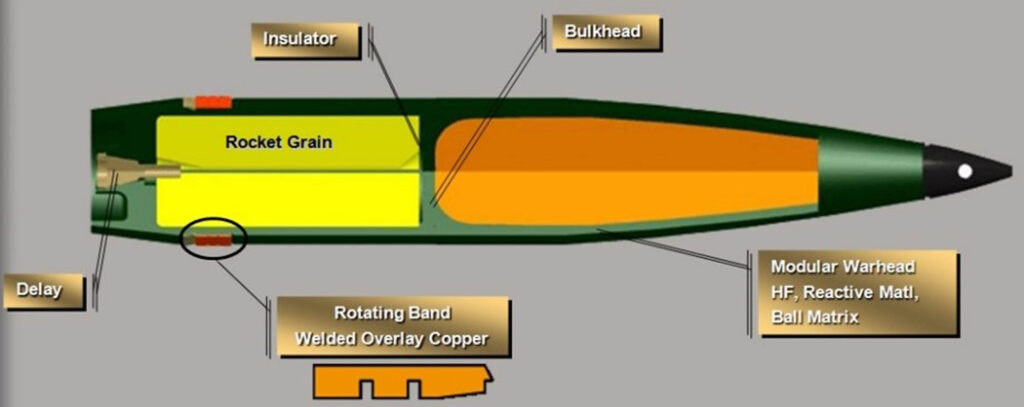

Even before Chief of Staff Milley made Long Range Precision Fires his No. 1 priority, the Army was working on Extended Range Cannon Artillery. ERCA has two aspects. First, the service is developing a new rocket-boosted shell, the XM113, with a 40 km range when fired from current cannon. The XM113 is now in testing, Maranian said: “We’ll see that in the hands of soldiers in about two to two-and-a-half years.”

Army XM113 prototype rocket-boosted artillery shell

Second, ERCA is lengthening the barrel of the howitzer by almost 50 percent (from 39 calibers to 58). The longer barrel is a harder to manufacture and more awkward to maneuver, but it lets the propellant push the shell longer, building up speed. The extended barrel should enter service in 2023, Maranian said, and combining the new ammunition with the new barrel and a new propellant, “we foresee being able to get that howitzer out to 70 km.”

The metallurgy of the new barrel should be robust enough to fire even more advanced munitions like hypersonic and ramjet rounds that enter service beyond 2023, Maranian said, although he doesn’t have a date yet. Experimentation will begin “within the next couple of years,” he said, but he thinks hypersonic cannon shells could reach out to 100 km (63 miles).

Army Multiple Launch Rocket System

At that range, Maranian said, cannon can take on targets that today require more expensive rockets. So what do the rockets do? Well, they get longer-ranged too. That means, in turn, that means rockets take over missions from the most expensive missiles, so those have to gain range as well.

The current precision rocket — the Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System, or GMLRS — fires about 70 km (44 miles). That’s roughly the same range as the upgraded ERCA cannon and shorter than hypersonics. So the Army is working on GMLRS Extended Range that will roughly double that, Maranian said, to about 150 km.

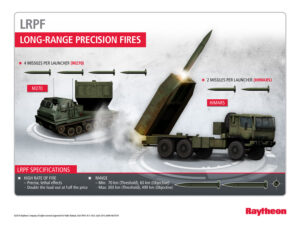

Then there’s the artillery’s longest-range system, the Army Tactical Missile System. (This is a “semi-ballistic” missile, not a true ballistic missile). ATACMS in its current form can hit targets about 300 km (188 miles) away. For the last few years, the Army has been developing a replacement that’s both half the size — allowing two in a HIMARS launcher or four in an MLRS — and longer-ranged. Officially, the new missile could go right up to the INF treaty limit of 499 km, although if the treaty collapses expect that number to go higher.

Raytheon’s proposal for the new Precision Strike Missile (PRSM), formerly the Long-Range Precision Fires (LRPF) weapon.

The ATACMS replacement was originally called Long Range Precision Firepower. But when the Chief of Staff designated “Long Range Precision Firepower” as his No. 1 modernization priority, he had a much wider range of weapons in mind — namely, the whole portfolio of advanced artillery Maranian’s discussing. So the weapon formerly known as LRPF will soon be formally renamed PRSM, the Precision Strike Missile.

Lockheed Martin and Raytheon will test-fly their PRSM prototypes next year, in 2019. The winner’s weapon should achieve Initial Operational Capability in 2023 — and then get upgraded over time. The initial PRSM will only be able to hit stationary targets on land, but the Army is working on seekers that would let it track and kill moving targets on both land and sea, including enemy warships — a particularly useful capability for Army batteries on islands in the Pacific. Other warheads under study would home in on radio and radar signals or loiter over the battlefield like drones, collecting intelligence and beaming it back.

M109A7 Paladin and its armored ammunition carrier.

In the longer run, Maranian said, the Army is looking at even more exotic technologies such as railguns — now being pioneered by the Navy — which use electromagnetism to launch projectiles at about Mach 7. And there are other projects moving along in parallel, like an automatic loader for the M109 Paladin howitzer to increase its rate of fire. Human loaders manage four rounds in the first minute, then one a minute thereafter as they tire, but the autoloader technology could offer 6-10 a minute as long as ammo is left.

All this investment in new technology is a marked contrast from the previous 20 years, when the artillery suffered two major program cancellations — the Crusader howitzer and then the howitzer variant of the Future Combat Systems. One of the Army’s most neglected branches is now the chief cornerstone of its approach to future war.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.