Army Wants Hypersonic Missile Unit by 2023: Lt. Gen. Thurgood

Posted on

The US Army’s Advanced Hypersonic Weapon, ancestor of several current programs.

PENTAGON: The Army will field a battery of truck-borne hypersonic missiles in 2023, with a contract award in August, the service’s new three-star Program Executive Officer said. The service will also field a battery of 50-kilowatt lasers on Stryker armored vehicles by 2021, he said. A program to put a 100-plus-kilowatt laser on a heavy truck, however, is under review and may be combined with Air Force and/or Navy efforts to reach comparable power levels, Lt. Gen. Neil Thurgood told reporters here this afternoon.

Thurgood’s recently reorganized and upgraded office will also take over key Army space programs, he said, but those organizations haven’t been brought under his command just yet.

Commonality is key, Thurgood said, with the three services combining their efforts and pooling resources wherever possible on these high-stakes, high-tech, high-cost programs. (Marine acquisition is mostly managed by the Navy).

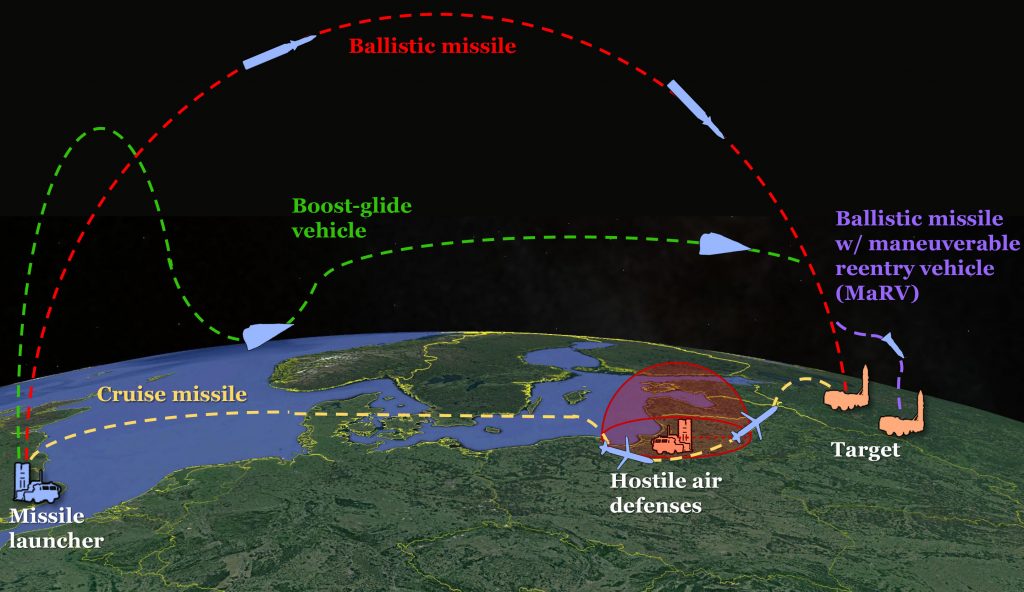

Notional flight paths of hypersonic boost-glide missiles, ballistic missiles, and cruise missiles. (CSBA graphic; click to expand)

Hypersonics

The Army will manage production of the Common Hypersonic Glide Body — the part of the missile that maneuvers — for all three services, Thurgood confirmed, although the Navy will lead the design work.

“We have the responsibility to build the industrial base in the US,” Thurgood said. “We kind of know how to build these things already; now what I have to do is create a capability to build a lot of them.”

Lt. Gen. Neil Thurgood speaks to reporters at the Pentagon Tuesday.

A glide body initially developed by Sandia National Laboratory has already flown successfully in 2011 and 2017, but those test models were laboriously built by the government. The design’s been refined into what is being called the Block Zero Glide Body. Thurgood’s office held an industry day for interested contractors in March and has already selected the winning vendor(s). Other Transaction Authorities (OTA) contract negotiations are still in progress, so he’s not allowed to name them, but he expects an announcement in August.

Meanwhile, the Navy will buy a common “missile stack” — the rocket booster that lifts the glide body to the edge of outer space — for both itself and the Army. The Air Force, however, will need its own booster designed to launch from aircraft.

Once the Army’s mated its glide bodies with the Navy-provided boosters, it will sheathe the complete missiles in an Army-unique canister and mount two side-by-side on a single heavy truck configured as a Transporter-Erector-Launcher (TEL) vehicle. (Navy ships and submarines will need different launchers). The missile will be too large for the Army’s MLRS and HIMARS launchers, so a new TEL will have to be developed, based on the existing Oshkosh M870 semi-trailer.

Four TEL trucks, with two missiles each, and a command vehicle using the Army’s long-serving and well-proven Advanced Field Artillery Tactical Data System (AFATDS) network, will form a battery. (That’s artillery equivalent of a company or cavalry troop, traditionally consisting of four to eight guns). The battery, in turn, will belong to a “strategic fires battalion” within the brigade-sized Multi-Domain Task Force, an experimental unit that has been conducting exercises in the Pacific since its creation in 2017. “Multi-domain” refers to new ways of coordinating operations on land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace, for example by using Army missiles to sink enemy warships or strike distant targets on land normally handled by the Air Force.

Army HIMARS trucks launch GMLRS (Guided Multiple Launch Rocket System) missiles

Like other elements of the Task Force, the hypersonic battery’s primary mission will be to test out new equipment, new tactics, and new ways to train soldiers to employ them. But it will have what Thurgood called a “residual combat capability”: In English, that means the eight missiles could be fired in an actual war, he said, “if the nation decides.”

Feedback from the initial battery, including soldiers’ input on any necessary technical fixes or improvements, will shape the Army’s decision on whether to proceed to a full-fledged acquisition program of record. At that point, Thurgood said, he’ll hand the effort over to a traditional Program Executive Officer. As the Army’s only three-star PEO, heading what’s now called the Rapid Capabilities & Critical Technologies Office (RCCTO), Thurgood’s only role is to carry promising technologies over the bureaucratic “valley of death” between the laboratory and production.

This way, Thurgood argues, the Army can test out new weapons as a functioning combat unit without committing to a full-scale production program. That said, to avoid delays and an expensive process of producing a few items, halting, and then restarting the line, it’s safe to presume production will start ramping up concurrent with the testing.

Laser-armed Stryker vehicle

Lasers

The Army’s tactical laser weapon is further along. First comes a 50-kilowatt weapon on the 8×8 Stryker, intended to shoot down low-flying drones, rockets, artillery shells, and mortar rounds. That’s part of the overarching Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense (MSHORAD) effort, which is also mounting traditional anti-aircraft guns and missiles on Stryker vehicles.

The first gun-and-missile prototypes will be delivered this year, under a separate program manager, with 144 vehicles expected to be in service by 2022. Thurgood is working specifically on the laser weapon, with a field test scheduled for 2021 and the first four-vehicle battery entering service late in Fiscal Year 2022 (which ends Sept. 30). As with the first hypersonic battery, he said, this unit’s primary role is to test out tech, tactics, and training, but it will be able to fight if needed.

Other Army laser programs, however, may be cancelled or merged with comparable efforts in the other services and the Office of the Secretary of Defense, Thurgood said.

Anti-aircraft Stryker variant chosen by the US Army for its Maneuver Short-Range Air Defense (MSHORAD) mission: 4 Stinger missiles on one side, two Hellfires on the other, with a 30 mm autocannon (and 12.7 mm machinegun) in between (Leonardo DRS)

What’s the difference? The Stryker’s a unique Army vehicle — although the Marines have the similar LAV — and its relatively small size was a good way to force competing companies to miniaturize their systems, Thurgood said. But when it comes to developing a 100-plus-kilowatt weapon, the challenge isn’t fitting it on a particular platform, he explained: It’s generating those power levels in the first place.

That means the three services can and should work together on the underlying technologies, he said. Yes, a laser on a truck faces very different atmospheric conditions, levels of vibrations, and other environmental factors than one on a ship or plane, but we need to develop the basic system before we can start tailoring it to service-specific environments.

“The vehicle it’s on is not the limiting factor,” Thurgood said. “Right now we’re just trying to get to higher power [levels].” The Army has its effort to put a 100-kW weapon on a truck, but the Navy is developing a laser in the 60 to 150 kW range, called HELIOS, to go on ships, while OSD has a demonstration program to build a 250-kW weapon (which is getting into the range required to kill cruise missiles).

Thurgood said he, his staff, and other Army offices are still reviewing the existing programs, the art of the possible, and the military need. Only then will he make a formal recommendation to Army leaders.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.