Army’s Message At AUSA: Don’t Cut ‘Foundational Force’

Posted on

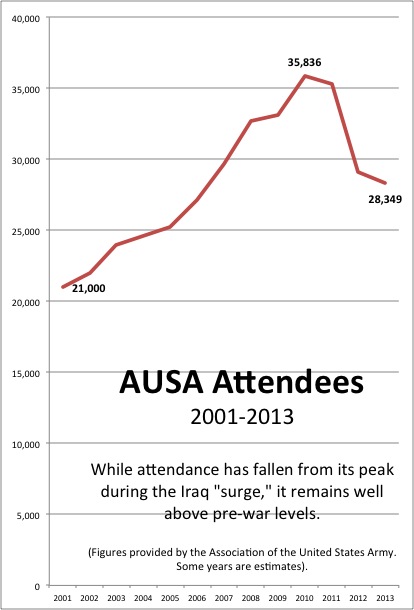

AUSA HEADQUARTERS: It is time for the tribes to gather. Monday is the opening of the Association of the US Army’s modestly named Annual Meeting. With roughly 30,000 people likely to attend over three days, it is the largest defense conference of the year despite a post-Iraq decline. This mega-event is also a microcosm of the Army in all its diversity, divisions, and dysfunction.

During the three-day conference in DC, as in the Army all year round, there is so much going on, and so much effort spent just communicating between factions within the Army, that it’s hard for the outsiders — the media, say, or Congress, which writes the checks — to discern any unifying message. But this year, both the Army association and the service’s priesthood, the Training and Doctrine Command (TRADOC), believe they’ve found a gospel that’s got legs: “foundational force.”

I’ll get to what that means in just a moment.

The Army story, “it’s such a difficult story to tell,” sighed retired Lt. Gen. Guy Swan, AUSA’s vice president for education, as we sat down at the association’s headquarters. “It does not resonate like airplanes and battleships and aircraft carriers…”

“Or ‘a few good men,'” I interjected.

“Right, or a few good men,” said Swan. “I was the chief of congressional affairs for three years and I ran into this constantly: [People saying] ‘You guys have a great story to tell but you’re never out there!’…. I think the Army in its narrative sometimes just speaks too narrowly about itself.”

Lt. Gen. Guy Swan, vice-president for education at AUSA.

Part of the problem is the sheer size and diversity of the service, which has more people and more missions than any of the others. Setting aside the notorious battles between the regular Army and the National Guard, branches as diverse as Special Forces, heavy artillery, and supply all have their own histories, bureaucratic turf, and “schoolhouses” at home bases around the country.

“The Army is a tribal organization. It’s always been that way,” said Swan. “We have Guard voices, we have active Army voices, we have Reserve. [With the conference], my view is that this an opportunity for the Army to speak with one voice.”

But what’s the message? That’s where “foundational force” comes in.

Army scientists study Ebola.

What is the “Foundational Force”?

“The Army is the foundational force for our national defense…because it provides capabilities that are used by all the services and indeed by our coalition partners and civilian agencies,” Swan said. “You see Gen. [David] Perkins talking about this, and [Lt. Gen. H.R.] McMaster,” he added, citing the commander of TRADOC and the head of TRADOC’s flagship Army Capabilities Integration Center (ARCIC) respectively. “When you start downsizing the Army…you are now undercutting those capabilities that everyone else relies upon.”

“If you’re a Marine artillery lieutenant, newly commissioned out of the Naval Academy, and you go for your artillery training, you go to the US Army Fires Center and School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma,” Swan said. “If you are a Navy petty officer on a ship and you’re issued a nine-millimeter Beretta pistol, that weapon came through the Army’s acquisition system. If you are a National Guard soldier, you go to active component-run schools and educational institutions. If you are a German soldier in Afghanistan, chances are your fuel is coming through the US Army logistics system.”

“I don’t think the narrative of the Army accounts for that enough,” Swan said. “It’s a force that does a lot of things for the nation and I think that is something we need to emphasize more as an Army. It’s not just ‘boots on the ground.'”

Putting boots on any kind of dangerous ground, of course, is exquisitely unpopular after 13 years (and counting) of land wars.

“We get it, the president does not want boots on the ground, that’s the nation’s policy right now, but as you’ve heard in testimony [by Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Gen. Martin Dempsey and others], we have to have options for all eventualities,” Swan said.

Army. Gen. Martin Dempsey, Chairman, Joint Chiefs of Staff.

“Clearly Americans — and soldiers — are really reluctant to get heavily engaged,” Swan said. Looking at Iraq and Syria, at Russia and Ukraine, at Liberia’s Ebola outbreak, all of which have required some Army response, he said, “this worries all of us: are we into another period of mission creep? We’ve all piecemealed into operations before where we’ve put our toe in the water and…you turn around and you’ve got thousands of people involved in this thing, and how did this happen?”

Even as the Army worries about overstretch, however, these crisis responses as currently configured haven’t required large conventional forces, what people traditionally mean when they say “Army.” That means the service can’t have a narrow narrative, Swan said.

“We’re all about tanks and Bradleys and Apaches; we all understand that piece and that’s kind of the non-negotiable piece,” he told me. But at the same time, “we are kind of doing our own reassessment of what value the Army provides and it’s not just necessarily the pointy end of the spear.”

“It may be a medical brigade in West Africa,” responding to Ebola, he offered. “It may be a theater missile defense capability in the Pacific” — like the THAAD launchers now on Guam — “or an advisor somewhere that’s got some expertise that we need, or a National Guard partnership with another nation.”

Congress, Sequester, and the National Guard

Congress, Sequester, and the National Guard

All this comes back to budgets, of course. “When you start getting into the debate about how big should the Army be — 420, 490, whatever it is — I think what gets lost in the discussion is all of these other enablers,” Swan said.

420,000 to 490,000 soldiers is the current official range of sizes for the active-duty Army, depending on whether sequestration cuts take full effect or not. But the size and missions of the Army Reserves and National Guard are also at stake, something which Swan acknowledges has caused problems. With the state Guard forces in particular having different legal authorities, lifestyles, and even loyalties than the full-time federal Army, he said, “there’s always tension in a system like that but it’s been made worse by the sequestration dynamic.”

But all parties agree sequestration is the common enemy. “I had lunch about two weeks ago with Gen. Hargett, [Gus Hargett, the president of the National Guard Association [of the United States]. We agree on more issues than we disagree on,” Swan said. “Obviously, the Apache helicopter thing became very confrontational, adversarial,” he understated, but the AUSA conference is “an opportunity to take a deep breath over Apache helicopters and how big should the Guard be and how big should the Reserve be,” a chance for “reaching across the aisle.”

Then AUSA, NGAUS, and the 29 other members of The Military Coalition (TMC) can form a united front against the budget cuts, Swan pledged: “As the Congress comes back into session after the election, [we] are going to make a concerted effort to once again push back on sequestration.”

If the military can get some relief from the sequester, as President Obama himself has urged, that reduces the pressure on the Army’s various factions and should lessen the likelihood they will fight bitterly for their slice of an ever-shrinking pie. But to make the case for cash to Congress, those factions need to agree on an effective message. Will “foundational force” do the trick?

If the military can get some relief from the sequester, as President Obama himself has urged, that reduces the pressure on the Army’s various factions and should lessen the likelihood they will fight bitterly for their slice of an ever-shrinking pie. But to make the case for cash to Congress, those factions need to agree on an effective message. Will “foundational force” do the trick?

We’ll have a much better sense in just three days.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.