Army Patches Its Network For Near Term

Posted on

A Samsung Galaxy loaded with the military’s ATAK command-and-control software

FORT MYER: The Army knows its network won’t work in a big war. It’s too vulnerable to hacking and jamming, too cumbersome to deploy and set up, too hard for soldiers to use.

So the service is trying to fix things. The long-term solution may take “big, leap-ahead technology,” said Maj. Gen. Pete Gallagher, head of the Cross Functional Team leading the network overhaul (more on that below). But, as Gallagher and other soldiers showed off here yesterday, short-term solutions can be as simple as replacing old server stacks with new ones one-third the size, replacing bulky metal antennas with inflatable ones, or loading new software on an off-the-shelf Android phone.

The Army Nett Warrior system uses Android.

Nett Warrior Declassified

Nett Warrior was the Army’s attempt to bring the GPS maps, “Blue Force Tracking” of friendly units’ locations, and digital messaging that are standard in command posts and vehicles to the sergeant on foot. It uses a standard Android Galaxy smartphone plugged into the tactical radio network (though it can use cell towers if available). But soldiers found it awkward and difficult to use — in part because of the interface, but in part because the device used classified data, subjecting users to all sorts of regulations like locking it up when not on mission.

So the Army loaded new software, the Android Tactical Assault Kit (ATAK), and downgraded the encryption. Now Nett Warrior only handles “secure but unclassified” data (though it can be reset to handle secret data if necessary) using off-the-shelf commercial encryption. That means troops can even take it back to the barracks to play around with and figure it out.

When I asked yesterday if I could photograph the screen — showing real-time troop movements in an exercise hundreds of miles away — the soldiers showing it off said sure. (See the top of this story) So what if the world saw? By the time it would take for me to publish my article, let alone for an enemy to crack the banking-sector-level encryption, the soldiers would be someplace else.

How much easier is the new Nett Warrior? Staff Sergeant Jason Roseberry of the 82nd Airborne told reporters here that his team got their devices just two days before heading to the Joint Reading Training Center for high-pressure wargames. “18 hours later, the soldiers…were messaging back and forth, pulling mission graphics down, talking over the radio,” he said. “There was no official training at all.”

Counting both the Rifleman Radios attached to Nett Warrior and more powerful models for higher leaders, there were about 240 radios for the 714 paratroopers in Roseberry’s unit, the storied 1st Battalion, 508th Airborne Infantry. When they arrived at the JRTC on Fort Polk, he said, “we had the full network up in probably five minutes.” Then they strapped on their radios and jumped out of airplanes with them.

A T2C2 inflatable antenna for satellite communications, with its carrying cases.

Streamlining the Network

Streamlining the network is especially essential for airborne troops, who travel light. Roseberry’s brigade in the 82nd is getting first crack at much of the new equipment.

Other simple but useful innovations include replacing heavy metal antennas used for satellite communications with inflatable ones. Air pressure keeps the parabolic dish in shape and inflates a protective ball around it. Soldiers with minimal training, doing a field test in Alaska in four-degree weather, managed to get it set up and connected to the network in under 30 minutes, an Army briefer told reporters. Packing it up just requires deflating it, folding it and putting it in three bags you could carry on a commercial flight or parachute out of a military plane. (This small system has a big name, Transportable Tactical Command Communications or T2C2).

Army command posts are replacing a 1,200 lb server stack (right) with one weighing 357 lbs.

The Army’s also lightening the server stacks that run all the networks in a brigade. Currently a brigade has three stacks, each taller than a man and weighing 1,200 pounds. But computing power keeps getting smaller and cheaper in the civilian sector, so the Army is issuing new stacks with the same capabilities that weigh 357 pounds apiece — and have room for future upgrades. Setup time has dropped from 30 minutes to ten. There’s also a miniature version of the server that runs off a laptop, which can maintain basic connectivity while the big stacks are being taken down, transported, and set up somewhere else.

The biggest “light” system the Army showed off yesterday at Fort Myer was a mobile Tactical Communications Node (TCN) that fits inside a Humvee. That may seem bulky until you compare it with the original, which required a three-axle FMTV truck.

While the new Tactical Communications Node is smaller, however, it still uses the same WIN-T software and hardware. That’s the Warfighter Information Network – Tactical that Army Chief of Staff Mark Milley decided was inadequate for high-intensity war.

The Army will stop buying WIN-T this year but will keep issuing the ones it’s already bought. When that’s done in 2021, every active-duty infantry and Stryker brigade will have WIN-T Increment 2, which can operate from a moving vehicle. Their National Guard counterparts and all armored brigades will have Increment 1B, which only works when stationary.

The goal, said Gallagher, is to “level set the Army with a common tactical network foundation” as a uniform starting point for future modernization.

Making Army network equipment lighter or easier to use is definitely helpful, but it doesn’t address the fundamental problems with WIN-T, the backbone of the network. Replacing WIN-T is one of those big, long-term efforts.

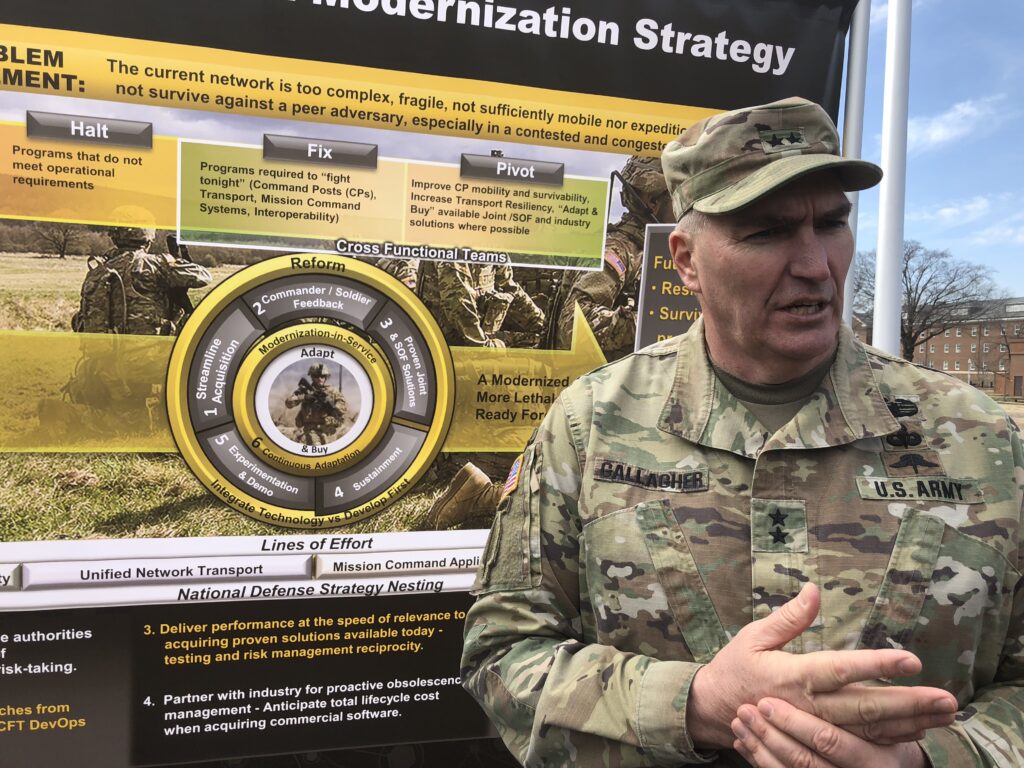

Maj. Gen. Peter Gallagher briefs reporters on Army network modernization

Halt, Fix, Pivot

The Army’s strategy is “halt, fix, pivot”:

- Halt further purchases of WIN-T and other flawed systems such as Command Post of the Future (CPOF) and the Mid-tier Networking Vehicular Radio (MNVR);

- fix the existing system with near-term experiments like those on display at Fort Myer; and

- pivot to what Maj. Gen. Gallagher calls “a whole new way of doing business,” not only using new technology but involving top Army leadership much more directly in directing network programs.

Gallagher was sparing with details, but he said his Cross Functional Team — one of eight working on top Army priorities — was focused on two aspects of the new network:

- Creating a more robust “transport layer” to move large amounts of data (what WIN-T does now) and;

- Making it interoperable with other US services and foreign allies. Other Army organizations will lead on other aspects, such as lightening command posts and simplifying the current array of command and control software.

Gallagher’s CFT is throwing out old assumptions — “in many cases we’ve held ourselves hostage by the way we’ve crafted those requirements,” he told reporters — and turning to companies outside the traditional defense industry — “not just the normal players.” A “tech exchange” in February at Aberdeen was attended by representatives of 204 companies, 87 of them small businesses, he said. Companies are now submitting white papers on potential solutions, both near-term and long-term. “A lot of aggressive experimentation and demonstration (is) ongoing as we speak,” he said, with ordinary soldiers providing feedback from field tests.

Humvee-mounted WIN-T TCN (Tactical Communications Node)

There are many problems to solve, but “probably the main effort (is) assured network transport in a contested environment against a peer adversary,” Gallagher said. “That’s where a lot of our science and technology efforts have been refocused on, and where we’re partnering with industry.” In other words, how can the Army plan stop the enemy from jamming our transmissions or tracing their sources for artillery strikes, electronic warfare techniques which the Russians used to devastating effect in Ukraine?

“There are a lot of innovative anti-jam solutions,” Gallagher said. “DARPA’s got some initiatives for small aperture Advanced EHF (AEHF) capability that we’re interested in and there are other anti-jam solutions that the (Army) CERDEC community and even industry (will) come back to us with.”

There are two complementary approaches, Gallagher and his aides explained. You can make individual point-to-point radio link harder to jam, and you can create alternative links — a so-called multi-path network — so that when one is jammed, troops can just switch to another. Army radios will need to use the kind of Low Probability of Intercept/Low Probability of Detection (LPI/LPD) transmitters now used on stealth aircraft. The software controlling the network will need to be able to do dynamic spectrum reallocation, quickly switching from jammed frequencies to clear ones. And the Army will need to replace its array of single-purpose radios with ones that can transmit a wide variety of signals.

It is a daunting and long-term task. In the meantime, Gallagher said, the Army will “leverage existing capabilities that are already proven by either our joint partners, the Special Operations community, or commercial-off-the-shelf solutions…already out there….to immediately fix our ability to fight.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.