Army Multi-Domain Update: New HQs, Grey Zones, & The Art of The Unfeasible

Posted on

Smart missiles to strike hard targets hundreds of miles away. Wireless links to pull data from stealth fighters and foot soldiers alike. Command posts agile enough to coordinate it all — not only in open war, but in the ambiguous “grey zone” of hacking, proxy warfare, and Twitter trolls. That’s just a few of the most crucial pieces of the Army’s new concept for Multi-Domain Operations out Thursday.

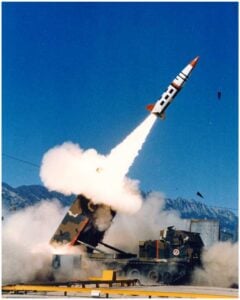

Army Tactical Missile System (ATACMS) launch. The US Army is now seeking much longer-range precision-guided, non-nuclear missiles.

One issue: None of this exists yet. The demands are particularly daunting for multi-domain command and control. The document calls for new high-capacity, high-security networks — when the Army is still rushing to patch its current systems — and strongly implies two new high-level headquarters focused on countering Russia and China — when the only existing such “Field Army” HQ is the 8th Army in Korea. So the Army can’t actually execute the concept today.

But that’s the point. “If you merely describe what you can do right now, it doesn’t drive modernization,” Lt. Gen. Eric Wesley told reporters Thursday afternoon. He’s head of the Army’s in-house thinktank ARCIC, soon to become part of Army Futures Command, which will take concepts for the future and turn them into working tactics, units, and technology. “A concept is the first thing you look at, something that you can’t do right now, and it’s a reach goal,” he said. “It is infeasible as it stands right now.”

When it comes to describing what the Army needs to do that it can’t do now, however, the generals have gotten a lot more specific in this edition of Multi-Domain Operations (informally, version 1.5). That’s as compared to the earlier Multi-Domain Battle concept (v1.0) rolled out last fall, which in turn expanded massively on the original 12-page white paper from January 2017 and sneak previews in 2016.

In their last two tries at revolutionary ideas, Army leaders either got too specific too early and failed to adapt to what didn’t work out (Future Combat Systems) or started out too vague and never got traction (Strategic Landpower). By contrast, Multi-Domain Whatever-You-Call-It has been shaped by two years of debate, wargames, and field experiments — not only within the Army but with the other services.

Going by what I’ve seen from the outside, the Air Force has had the most impact, with the Marines content to quietly follow the Army’s lead, while the Navy has nibbled around the edges, so far eschewing the “multi-domain” buzzword. The net result? A concept that’s matured dramatically since it began, without losing its essence: a call for all the services to orchestrate a “a perfect harmony of intense violence” across all domains — land, sea, air, space, and cyberspace — to defeat sophisticated adversaries such as Russia and China.

The Gray Zone

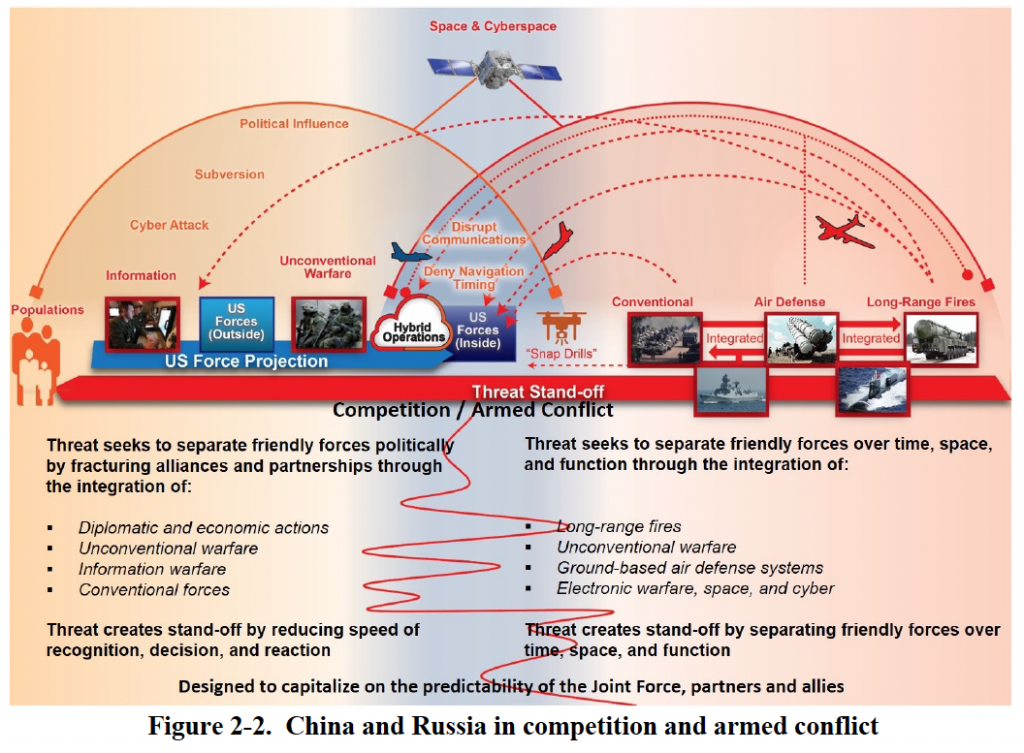

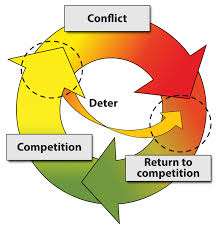

The most obvious change is the name, but it’s more than just words. The Army’s shift from Multi-Domain Battle to Operations was meant to broaden the focus from just fighting — tactics — to a wide range of operational and even strategic concerns. Today’s document backs this up with extensive sections on what the Army must do in “competition,” the “gray zone” between peaceful cooperation and open war, in which authoritarian and adaptable adversaries like Russia and China pursue their goals aggressively but not violently through everything from propaganda to proxies to military positioning.

Yes, “competition” featured in the Army’s October 2017 Multi-Domain Battle paper and in Defense Secretary Jim Mattis’s January 2018 National Defense Strategy. But this latest Army concept gives competition more depth and emphasis, elevating it beyond mere preparation for war and “shaping the theater” to the Army’s primary mission:

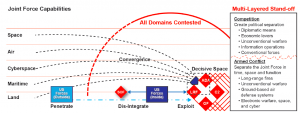

“The central idea …. is the rapid and continuous integration of all domains of warfare to deter and prevail as we compete short of armed conflict,” the document says prominently (boldface in original). “If deterrence fails,” it continues, then the Army engages in armed conflict to “penetrate” enemy defenses, “dis-integrate” them (the hyphenation is deliberate), “exploit” the resulting weak points, and “consolidate gains to force a return to competition on terms more favorable to the US, our allies and partners.”

“It’s a recognition of the reality that we’re in competition all the time,” said Gen. Stephen Townsend, who as head of Training & Doctrine Command (TRADOC) is Lt. Gen. Wesley’s boss until mid-morning Friday, when ARCIC transfers to Futures Command.

“An example of when our Army and our nation competed very well (is) the Cold War,” Townsend said. “We defeated the Soviet Union, then our near-peer adversary threat, and we never fought them directly, (though) we did fight their proxies (and countries using) their equipment.”

“We’ve been competing for years, but not on this scale,” Wesley added. “What’s changed is our peers identifying over the last 30 years that, if you engage the United States in combined arms maneuver” — as Iraq tried twice, in 1991 and 2003 — “we’re really good at that, and so they have sought to achieve their operational and strategic objectives short of conflict, short of war.”

Most of the tools of competition listed are familiar, if historically under- or ill-used: public diplomacy, clandestine surveillance, uniformed advisors, military exercises. But the Army can explore new options, like using exercises to show off specific war-winning capabilities — while obfuscating the details of how they’d actually be used. (My example, not theirs: firing off long-range missiles at distant targets but using different targeting sensors and communication frequencies than in real war).

“We need to do a better job of demonstrating capability, demonstrating that we can defeat a component or components of a threat system,” said Brig. Gen. Mark Odom, Wesley’s point man on drafting the concept. Most international exercises today focus on training with and reassuring US allies, often under strict constraints to avoid being perceived as provocative. “There may be political reasons we can’t do that in places like Europe or the Pacific,” Odom said, “but there’s nothing that prevents us, in many cases, from doing it in the United States and making it visible.”

New HQs, New Networks

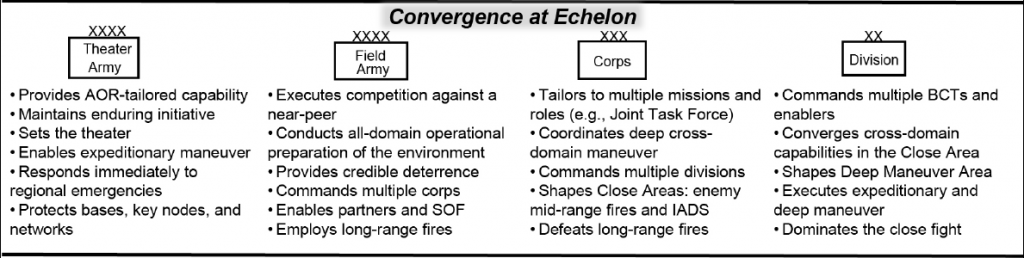

While the technologies and organizations to do it don’t exist yet, the new document is also much clearer on which part of the Army needs to do what, in conjunction with which of the other services, civilian agencies, and allies. There’s even a detailed multi-page breakdown of responsibilities at each level or “echelon” of command.

Those levels include the new Field Armies, an intermediate layer between theater Army commands permanently established abroad, like US Army Pacific (USARPAC) or US Army Europe (USAREUR), and Army corps HQs, which deploy from the US as needed. Today, the only Field Army is the 8th in Korea, where a war would involve so many troops, mostly Koreans under US command, that it would require its own four-star headquarters close at hand, rather than being coordinated by USARPAC in Hawaii. But the new MDO concept calls for multiple field armies in “regions that have near-peer threats” — which other pages unambiguously identify as China and Russia.

Army officials confirmed to me after today’s briefing that the new MDO concept does indeed envision new Field Army HQs capable of commanding multiple Army corps at once against a major threat. Where to put them is a subject for future study.

Land-based missiles deployed at “Expeditionary Advance Bases” could form a virtual wall against Chinese aggression (CSBA graphic)

My informed speculation? Given the concept’s clear focus on Russia as “the pacing threat” in the near term, the first new Field Army will almost certainly focus on Eastern Europe. China is depicted as the larger threat in the long term, because of its growing economy, but where a China-focused Field Army would end up is unclear. Thinktank proposals for Army missile bases on Western Pacific islands would make southern Japan or the Philippines ideal, but the politics of US presence in either country are fraught.

Even in strictly military terms, field armies will be contentious because they create another layer of headquarters between the top commanders and the combat troops. That goes against the grain of Information Age organization, which tends to flatten hierarchies, bypass middle management, and move information rapidly across all levels. It also reverses the Army’s 2003 decision to deemphasize higher headquarters and make brigade combat teams more independent.

After the Soviet Union fell, Lt. Gen. Wesley said, the Army could afford to organize around the brigade because, bluntly, nobody could stop a single American combat brigade with proper backup from airpower. That was especially true for 17 years of counterterrorism and counterinsurgency, where division and corps headquarters focused on supporting and coordinating independent operations by their individual brigades, not converging multiple brigades on a single target. But China and Russia can stop both lone brigades and the airpower they’ve come to depend on, forcing the US Army to operate on a larger scale and to bring along more land-based long-range firepower of its own.

That said, the Army also wants to work even more closely with the Air Force, Navy, and Marines than it has in Afghanistan and Iraq, and it wants to share information more rapidly and widely than ever, even as it increases the layers of hierarchy. Both those desires depend on new organizations, new processes, and new technology.

“The concept drives requirements,” Wesley said. “It’s not coincidental that one of our priorities for investment is the network… so we have the ability to communicate that kind of target very quickly to another domain.”

Perhaps the biggest challenge for this future network: It needs to be “sensor-agnostic,” Townsend said. “Maybe it’s a private with AI goggles that sees the golden egg we’re looking for, or maybe it’s an F-35, or maybe it’s a satellite, or maybe it’s an electronic warfare collection asset… we don’t care who sees it,” he said. “What we want is… if anything in DoD sees that thing we’re looking for, every one of us will know it.”

“We don’t have that,” he freely admitted. Not yet.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.