Army Issues Lighter Armor For Bigger Wars

Posted on

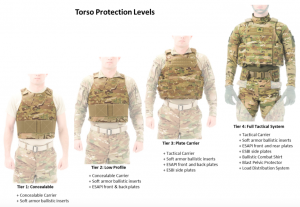

The Army’s new body armor package, the Soldier Protection System, is designed to scale up and down depending on the tradeoff commanders want to make between protection and mobility.

After a generation of guerrilla warfare, the Army is issuing new, lighter body armor that can be tailored for a wider range of missions, from plainclothes advisor roles to high-intensity combat. It’s part of a new push to improve infantry equipment, from rifle calibers to targeting optics to augmented reality training, coming from the Secretary of Defense himself.

Lt. Col. Ginger Whitehead, Army Product Manager for Soldier Protective Equipment, shows off the new, better-fitting female body armor.

“We have to have the ability to scale up…and scale down,” said Lt. Col. Ginger Whitehead, “from armed individuals with rifles — maybe they’ll have an RPG or grenade … all the way up to a near-peer, where you’re going to see the full gamut of weapons systems,” from heavy machinegun bullets to Russian-style storms of artillery shrapnel.

The solution now entering service? A Soldier Protection System of carefully thought-out pieces that the wearer can mix and match to meet the mission, said Whitehead, a Iraq veteran who’s now Army product manager for soldier protective equipment. Soldiers can strip the new system down to a 2.8 pound vest concealed under their uniforms or even civilian clothing to stop handgun rounds — ideal for advisors who want to keep a low profile but who might get shot by their erstwhile advisees in a so-called “green on blue” incident. (The first units to get it are the Security Force Advisory Brigade headed to Afghanistan). Or they can layer on armor for all-out combat, with a mix of hard plates and soft (kevlar-like) fabrics to stop bomb blasts and shell fragments — but without weighing them down as much as earlier armor kits.

“You’ve got to climb over obstacles, you’re getting in and out of vehicles, you’re low-crawling,” Whitehead said. “Even with your marksmanship” — which requires fluidly raising and aiming your rifle — “the more range of motion you’ve got, the better off you are.”

The rugged Afghan mountainsides force soldiers to hike miles uphill, weighed down by heavy body armor and often outmaneuvered by lightly equipped Taliban.

Slow Is Dead

There’s a lot of history here. In Afghanistan and Iraq, the Army had to uparmor its soldiers in a hurry, just as it uparmored its vehicles. That armor saved lives, but for humans and Humvees alike, the layers of protection grew so heavy they often impaired mobility.

The price of protection had many parts. Heavy armor slowed soldiers climbing Afghan mountainsides or boiled them in Iraqi deserts. Ceramic plates cut off circulation when smaller soldiers — including most women — sat down in vehicles for hours-long convoys. The backs of helmets snagged on collars when soldiers hit the dirt and went prone, making it harder to turn your head to see. Torso armor restricted arm movements, impairing aim.

Troops in Iraq typically patrolled in vehicles, so armor that weighed them down when moving on foot seemed a minor tradeoff for increased protection.

In Iraq, for many missions, these trade-offs were tolerable: Soldiers spent a lot of their time on bases or in vehicles, and if they waddled like the Michelin man when they got out, it was a small price to pay. In Afghanistan, where much of the country is only accessible on foot, the weight meant US patrols were often outmaneuvered by lightly equipped Taliban. And in a major war, with heavy weapons firing all around, soldiers absolutely have to be able to sprint, crawl, and climb from one foxhole, rock, or ruined building to the next. Having so much armor it slows you down can kill you just as dead as having no armor at all.

The Army invests heavily in researching lighter-weight armor, and Whitehead says they’re in negotiations with industry for a new generation of rigid armor plates that should weigh 10 to 20 percent less. But the big weight and mobility gains in the new system come from careful design — the tailoring, if you will. “These are not wildly different materials. (They’re) a little bit lighter,” she told me. “It’s mostly … a different design.”

Army soldiers train in full armor at the peak of the Iraq War in 2009. Note the awkward trapezoidal groin protection, widely detested by wearers.

A Better Fit

Consider groin protection, a particularly sensitive area. After being wounded by a roadside bomb, many male soldiers’ first question is whether they’ve been castrated by the blast.

The old armor had two pieces. One was a protective undergarment, basically “ballistic underwear,” Whitehead said, with inserts to protect the femoral artery inside the thigh. The other was a rigid trapezoid — not a shape normally associated with the human body — that attached to the soldier’s belt and to straps running back between the legs, giving the wearer what Whitehead said amounted to a permanent wedgie. Soldiers, understandably, hated it.

The new armor’s torso, groin, and high protection can be layered or slimmed down depending on the threat.

The new system consists of a single flexible garment covering the inner thighs — that femoral artery again — and groin. In a recent field-test at Fort Lewis, Washington, “their response was overwhelming,” Whitehead said. “They’re not walking bowlegged, they’re not chafing. It’s more comfortable, particularly when it gets hot.”

There are similar, if less obvious, improvements in the torso armor. It’s cut shorter, making it easier to bend at the waist and to sit down in vehicles. It’s also got larger openings around the shoulders, letting troops raise and aim their rifles better. That reduces the area covered with the thickest protection, but Army research shows that wounds in the specific areas affected are very rare. In fact, the Army will soon start testing a “shooter’s plate” that cuts the rigid armor plate even further back from the shoulders to further increase freedom of movement.

As a female soldier, Whitehead particularly appreciates a number of subtle improvements, from a greater range of smaller sizes — early armor tended to run huge — to a helmet that doesn’t get hung up on your regulation hair bun. Only one piece of the kit is actually gender-specific, however: Women get a vest with relatively shorter sleeves, a wider waist, and a notch in the back of the collar to accommodate the omnipresent bun. Countless comic books and video games aside, female armor does not require conspicuous bulges, although Whitehead says the Army is trying out additional padding under the armor plate to improve comfort for particularly well-endowed servicewomen.

Improvements will continue, Whitehead said, driven by both new technology and soldier feedback. Probably the most crucial item: a more bullet-resistant helmet –particularly important when taking cover against rifle rounds or shrapnel whizzing overhead.

The first try was modular headgear that weighed 5.8 pounds with all the pieces in place, which soldiers rejected in field testing as too heavy. So the Army went back to the drawing board and is testing Next Generation Integrated Head Protection that, among other things, replaces some traditional materials with polyethylene.

“We’re in the middle of testing right now,” Whitehead told me. “If the vendors can make this and it can pass ballistic testing, this will be a game changer.”

“These are exciting times,” she told me. “We’re saving lives.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.