Army Futures Command: $100M, 500 Staff, & Access To Top Leaders

Posted on

WASHINGTON: Army Futures Command just officially stood up Friday, but the service has big plans for its new HQ, created to unify rival modernization bureaucracies. Not only will the command ultimately grow to roughly 500 staff and an annual budget of up to $100 million, overseeing the service’s entire $30 plus billion modernization portfolio, Army Secretary Mark Esper said this morning: AFC’s commander and his key subordinates should have direct and regular access to Esper’s successors and other top leaders.

Army Secretary Mark Esper (left) and Chief of Staff Gen. Mark Milley testify before the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Esper and the Army Chief of Staff, Gen. Mark Milley, pore over the modernization budget program by program and get weekly briefings on their top priorities, he told a Defense Writers Group breakfast. He wants that to become a new norm, he said: “What you want is a process to become a habit, something you do every day, like getting up and brushing your teeth.”

But can Futures Command sustain this momentum? It’s pretty popular with Congress right now, but every dollar and every staffer added gives ammunition to skeptics who say it just adds another layer of bureaucracy. At the same time, AFC is still too new to have grown the local roots that protect most bases from being closed, and even at 500 people it’ll be a fraction of the size of the major bases. (Fort Bragg, the biggest, has 77,000 soldiers and civilians). If AFC doesn’t deliver quickly, let alone suffers a high-profile failure, or a new administration decides to cut all headquarters across the board as Obama did, it could easily be neutered.

A subtler but equally significant danger to AFC is that top leaders might lose focus. Yes, Secretary Esper, Chief of Staff Milley, and their respective deputies — Undersecretary Ryan McCarthy and Vice-Chief James McConville — have paid close personal attention to what is, after all, their own creation. But there’s no guarantee their successors will be as engaged.

Hands On

“I’m a very hands-on person,” Esper said. “We have done something unique. The chief (Gen. Milley) and I spent 40, 50 hours going through the equipping budget, and we will do that again in a few months as we look at (fiscal year) ’21, but we’re also going to apply the same level of scrutiny to every other budget in the Army,” notably training, personnel, and installations.

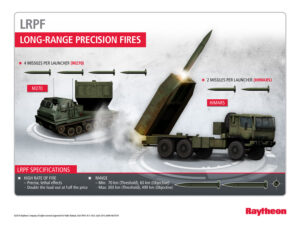

Raytheon’s proposal for the new Precision Strike Missile (PRSM), formerly the Long-Range Precision Fires (LRPF) weapon.

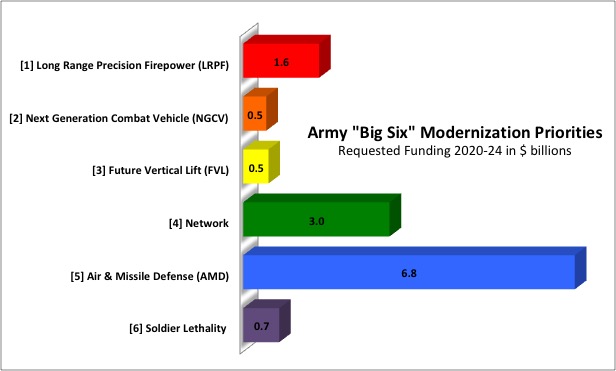

Esper’s personally gone through 800 modernization programs seeking lower priority items he can cut or cancel to free up funding for his top priorities: long-range artillery, armored vehicles, aircraft, networks, air and missile defense, and soldier equipment, in that order. Each of those Big Six has a dedicated Cross Functional Team led by a combat-hardened brigadier or major general, with a small team pulling together acquisitions officials, technologists, and requirements writers from across the sprawling Army bureaucracy. Two additional CFTs focus on fundamental technologies: Precision Navigation & Timing (PNT), and augmented reality training. The eight teams embody the new approach of bringing rival bureaucratic tribes together to get decisions faster, and the CFTs will be a central element of Army Futures Command.

Bell V-280 Valor tiltrotor in level flight with rotors facing forward. The V-280 is widely considered the leading candidate for the Future Vertical Lift assault aircraft but would need to be scaled down for the FARA scout.

“Every week that I am in DC,” Esper said — and he does travel a lot — “the chief and I are getting a CFT brief up. We just did one yesterday on air and missile defense, I think the week before that was… future vertical lift (i.e. aircraft). We’re circulating through them.” His staff confirmed that he sees all eight teams in rotation.

Esper’s constantly exhorting the teams, he said, to speed up their modernization programs, get rid of unnecessary requirements, and get prototypes in soldiers’ hands ASAP so real troops can give feedback on how the new technology actually works in field conditions. The Army’s also stuck to its priorities since Gen. Milley announced the Big Six last October, a month before Esper was actually confirmed. This stability — in contrast to past high-level flip-flops — gives industry the confidence to invest its own money, Esper said.

But that kind of hands-on attention from top leadership is hard to sustain, I noted. How can Esper and his cohorts ensure their successors do the same?

John “Mike” Murray’s wife, daughter, and granddaughters ceremonially “pin on” his new four-star insignia. Army Secretary Mark Esper smiles on in the background.

Setting Patterns

“What I hope will happen is the expectation will be that CFTs (Cross Functional Teams) and Army Futures Command will always have a place on my schedule and the chief’s schedule,” Esper said. Over time, he said, “it becomes a routine, a practice that we’ve done and have always done, and so that becomes the expectation not just for AFC and the CFTs, but for future service secretaries and future chiefs of staff.”

Now, it would help Army Futures Command fight its way onto future leaders’ schedules if it had the institutional heft to demand their attention. But bulking up AFC to help it win bureaucratic battles is directly contrary to the faster-better-cheaper ethos of the Army’s current reforms. So the organization has to walk a tightrope between being too big and not big enough, all within strict legal and fiscal constraints.

Now, it would help Army Futures Command fight its way onto future leaders’ schedules if it had the institutional heft to demand their attention. But bulking up AFC to help it win bureaucratic battles is directly contrary to the faster-better-cheaper ethos of the Army’s current reforms. So the organization has to walk a tightrope between being too big and not big enough, all within strict legal and fiscal constraints.

While AFC is standing up a small headquarters in Austin from scratch, most of its subordinate organizations are already in existence and won’t move from their current locations. Those are the Army’s research, development, and engineering laboratories (RDECOM), its in-house think-tank on future war (ARCIC), and its acquisition programs (PEOs and PMs), the last of won’t be under AFC’s direct command because the law requires them to answer to the civilian chief of acquisition.

Perhaps the single most important element is that AFC’s commander is a four-star general, one of less than a dozen in the active-duty Army. Today that’s Gen. John “Mike” Murray, officially promoted to that rank on Friday. Much of how Army Futures Command takes shape is up to him, Esper said.

“Time will tell. Gen Murray has to think through his organization,” Esper said when asked about AFC’s future structure. But, the secretary went on, “in terms of our advance planning, we see it on par with its sister major commands. (Those are namely Army Forces Command, which controls non-deployed units; Army Materiel Command, which historically owned the labs; and Training & Doctrine Command, which until now handled future warfare concepts). That means an operating budget of around $80 to a $100 million give or take. We expect five hundred people, plus or minus.”

Those figures comport with what other Army officials have been saying, although we haven’t heard it from one of the service’s most senior leaders until now. But of course it’ll take time to grow to those numbers. The hard part will be getting the command to take root before the top leaders change.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.