Army Boosting Laser Weapons Power Tenfold

Posted on

Laser-armed Stryker at Fort Sill.

ARLINGTON: The Army is dialing up its lasers, from 5 to 10 kilowatt weapons that torched quadcopters in successful tests to 50 to 100 kW weapons that could kill helicopters and low-flying airplanes — and, possibly, blind cruise missiles as well. Given rising anxiety over Russia’s Hind gunships, Frogfoot fighters, and Kalibr missiles, the technology is timely.

Army High Energy Laser Tactical Test Truck (HELMTT), formerly the HEL Mobile Demonstrator (HEL-MD)

A truck-fired 50 kW weapon — an upgrade of the lumbering HEL-MTT — will be test fired next-year. A 100 kW weapon on a more mobile vehicle — perhaps an 8×8 Stryker or tracked Bradley — will test-fire in 2022. The Army expects to issue the contract for that demonstrator before the current fiscal year ends October 1.

The 50 kW weapon will “obviously have a little more range, a little more power, a little better beam control,” Lt. Gen. James Dickinson, chief of Army Space & Missile Defense Command (SMDC), said to an Association of the USA Army breakfast this morning. “(Instead of) small quadcopters… it allows you to engage different or larger types of targets, so potentially rotary wing, fixed wing (aircraft).”

Dickinson was leery of discussing details — it took a couple of pointed questions for me to get that much out of him — but bear in mind the name of his command is “missile defense.” A weapon that can defeat manned aircraft can hurt incoming cruise missiles as well. Ballistic missiles are a tougher target, since their warheads are hardened against the heat of reentering the atmosphere from space.

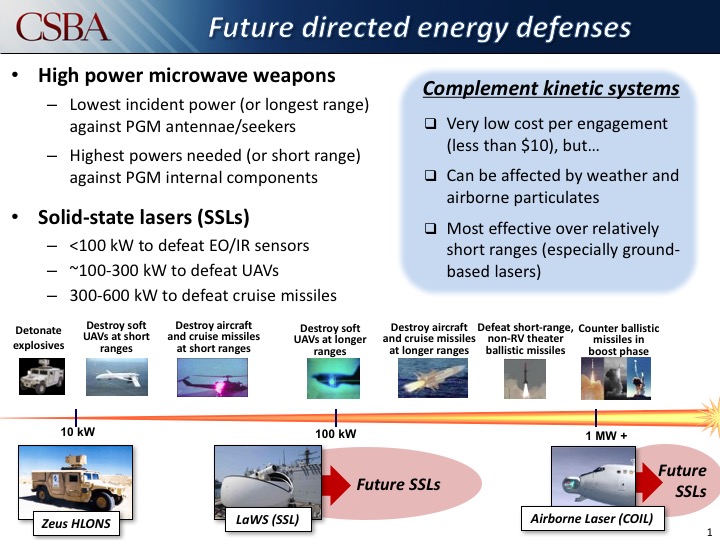

Estimated power ranges for lasers to shoot down different types of targets (Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments)

“I don’t think 100 kW would be enough to zap cruise missiles out of the sky, (but) 100 kW — and even lower — may be sufficient to blind/degrade some weapon sensors,” causing them to miss, said directed energy expert Mark Gunzinger, of the Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments.

“There are quite a few targets 60-100 kW lasers could be used to degrade or defeat, including rockets, artillery rounds, some missiles, UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles), etc.,” Gunzinger told me in an email. “We are talking short ranges for ground-based 100 kW-class lasers to achieve ‘burn-through’ kills on UAVs or rockets, (but) sometimes a functional kill — blinding or burning out a sensor a weapon uses for final guidance to a target — is good enough.”

“For missile defense, some consider 300 kW an important threshold for countering some types of cruise missiles, assuming the attack geometry requires a head-on shot (because) the cruise missile is coming directly at a defended asset,” Gunzinger told me. “Lower power lasers may be effective against the softer sides of cruise missiles.” Getting side shots would probably require a network of lasers around any given target to ensure at least one could get the right angle on an incoming weapon. That said, he emphasized, “I’m skeptical that 100 kW would be sufficient for CMD (cruise missile defense), even with side shots.”

M1 tank at the National Training Center in 2015.

Maneuver Warfare, With Lasers

The 50 kW laser will be on an upgraded version of the current 10 kW HEL-MTT (High Energy Laser – Mobile Test Truck), which is a converted HEMTT, a four-axle, 34-foot-long supply hauler. The 5 kW MEHEL (Mobile Expeditionary High Energy Laser), by contrast, is built into a much smaller and more mobile eight-wheel drive Stryker armored vehicle, able to keep up with frontline forces over rough terrain. The Army’s goal is to get its future 100 kW weapon small enough to fit on something as mobile as the Stryker, though not necessarily the Stryker itself.

Lt. Gen. James Dickinson (AUSA photo)

“The Mobile Test Truck… that’s a pretty big piece of equipment,” Dickinson told reporters after his formal remarks. “If you look at some of our missile defense systems, they’re big like that too: THAAD, Patriot. (But) our goal is to try to reduce it as much as possible.

“We want to put it on a common platform,” Dickinson explained, meaning a vehicle widely used throughout the Army’s frontline forces. “We’ve done that with air defense before. We actually had Bradley fighting vehicles that had Avenger-type mounts on them (the M6 Bradley Linebacker). So our goal is to always be on the common platform that the Army is using that day. If it’s Stryker, we’ll try to get it on the Stryker (but) we don’t know if that’s where we’ll be.”

While Dickinson didn’t speculate about alternative platforms, the only other suitable combat vehicle currently in production is the tracked Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV), a turretless utility variant of the Bradley family. Four-wheel-drive trucks like the Humvee and new Joint Light Tactical Vehicle (JLTV) are much smaller and much less mobile over rough terrain than tracked vehicles or an 8×8 like the Stryker. The Army has emphasized Maneuver Short-Range Air-Defense, meaning anti-aircraft units (and anti-drone and, potentially, anti-missile) must be able to keep up with the frontline combat forces.

Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV) at the AUSA annual conference.

Dickinson also said his command was supporting the Army’s new experimental unit, the Multi-Domain Task Force. Driven by the theory that the future force must fight not just on land but in all domains — land, air, sea, space, and cyberspace — the Multi-Domain Battle initiative aims to build a small unit, perhaps 1,500 troops, that has the same access to satellite intelligence, long-range artillery, offensive cyber assets, and more that only a 5,000-strong brigade or larger unit has today.

“We’re just now looking at that, in terms of what our part of the Multi-Domain Task Force would be,” Dickinson said. “In general, today we provide (units) satellite communications support (and) missile warning….As that task force comes together and it’s further developed, we will see exactly what the requirements will be.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.