AI, Initiative, & Lots Of Smart Bombs: Gen. Perna On Supplying Major Wars

Posted on

HUNTSVILLE: The arsenal of democracy needs an update. After a generation of grueling guerrilla warfare, the Army’s four-star senior logistician told me, the supply system has to get a lot more nimble for high-tech, high-intensity, high-speed future conflicts. Those changes, Gen. Gustave Perna said, include ramping up production of precision weapons and other essentials, adopting artificial intelligence to make sense of mind-numbing masses of data, and, above all, empower soldiers and civilians alike to take some calculated risks.

All that requires major cultural change at the massive organization Perna runs, Army Materiel Command. And AMC is already coping with the aftermath of the service’s biggest reorganization in 40 years, having given up its R&D labs to the newly created Army Futures Command. The intent was to create one organization focused on inventing the future force while AMC and other major commands focus on supplying, maintaining, and training the current one.

To do that mission, however, Army Materiel Command can’t just fall back on World War and Cold War patterns of mass production and bureaucratic management. Victory in modern conflict increasingly depends less on amassing iron mountains of supplies than on rapidly fielding new technology, updating software, and coping with relentless cyber attacks on the supply chain.

Living With Risk

Potential adversaries don’t need to blow stuff up to tangle US supply lines in a major war, Perna said: “They just have to figure out how to disrupt, not necessarily destroy or eliminate.”

Indeed, Russia and China prefer to accomplish their objectives without firing a shot working, in the grey zone between peace and war: hacking, cyber-espionage, social media subversion, and deniable proxies. Protecting against these threats puts an obvious premium on cybersecurity, for both the Army’s own logistics systems and its contractors: It’s naïve, Perna warned, to imagine our adversaries can’t figure out who’s making what for us and target key manufacturers.

But no amount of cybersecurity can stop all threats. So Army Materiel Command is systematically seeking backup suppliers so that it can work around any one point of failure, whether that’s a cyber attack, a company going out of business, or simply a small facility being overwhelmed by a sudden wartime surge in demand. “We create duplicative capabilities so we have multiple places to go,” Perna said. “That’s why the partnership with industry is so important…. We want to partner and spread it out.”

A supply chain with multiple options — a supply web, if you will — that can adapt rapidly to disruptions is not the traditional, bureaucratic, industrial age way of doing business. It requires a mix of mental agility, improvisation, and initiative, what the Army refers to as mission command: giving subordinates both a clear objective and lots of leeway on how to get there, rather than a rigid top-down plan that tries to eliminate any uncertainty.

“We may never eliminate risk, [so] commanders must always understand risk,” Perna told me. “We need to work through mission command, commander’s intent, and we need trust our workforce all the way down.”

Trust Your People

Technology has huge potential to help, but it can all too easily become a tool for micromanaging people instead of empowering them, Perna told me. At one point, he said, some of his subordinates proposed a new feature for the command’s Enterprise Resource Planning (ERP) system, already a complex and ungainly piece of software: They wanted an override that would prevent anyone from canceling a requisition without the approval of the HQ in Huntsville.

Perna said no. “We need to communicate and hold people accountable,” he told them. “Not spend millions of dollars putting in a failsafe button that says you can’t cancel unless I say so at the highest level….. It slows the whole process down!”

“We have to eliminate — this is essential — we have to eliminate these cookie cutter solutions from the highest levels, [where] we had one incident or we had one bad contract or we had a bad weld… so we start directing… ‘you will do all contracts this way, you will do all welds this way, you will do all purchases this way,” Perna said passionately.

“Mission command, it’s not just generals and colonels and sergeant-majors,” Perna said. “It really needs to extend from the highest commander all the way down to the lowest private and the artisans in our workforce.”

Or even contracting officers, Perna continued: “If they knew they were empowered to be innovative, they might actually create a contract that would reduce the cost,” he said, “but there’s such fear [that]we constrain them, we limit them — and shame on us.”

To pull this off, Perna cautioned, “you have to a well-trained, well-disciplined, and high-standard force” — not just the uniformed personnel but civil servants, depot technicians, and private-sector contractors. But, he continued, “if you have this foundation, then you can call audibles, then you can empower.”

Getting Smart On Smart Weapons

One example of a more collaborative, less bureaucratic approach is the Army’s push to increase production of precision-guided munitions, Perna said. Missiles, smart bombs, and guided rockets can run short even in campaigns against Third World adversaries, and a major war against Russia or China would require much larger stockpiles.

Tapped by Army leadership to fix the shortfall, Perna brought together both Army Materiel Command’s logisticians — who report to him — and the acquisition corps’ program mangers — who report to the civilian assistant secretary. After the two groups had studied the mismatch between war plan needs, the current stockpile, and manufacturing capability, they went to the private sector, not with a top-down plan, but with open invitation to offer suggestions. (This kind of dialogue has often been difficult).

“We brought industry in and we said, ‘okay, here’s the problem set, let’s figure out solutions,'” Perna said. “You’ve got to come to the table and stop B.S.-ing each other.”

Today, “I think we have a good foundation,” Perna told me, but building up the industrial base will take time and money. Before World War II, he noted, the military and industry started “priming the pump” as early as 1937 — but even then, it took until 1943 to get enough ammunition and equipment for major offensives. A 21st century adversary won’t give us that much time.

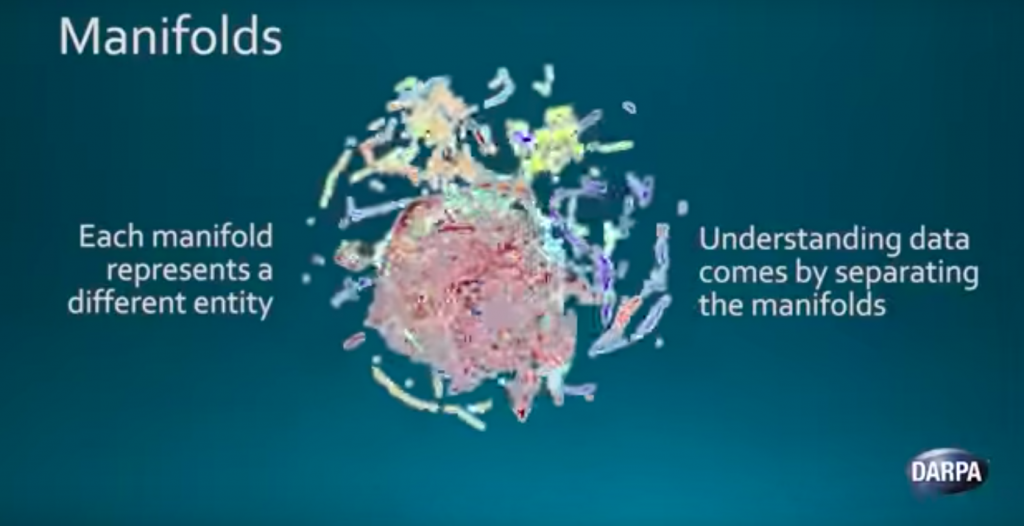

Modern machine learning AI relies on the fact that, in any large set of data, there will emerge clusters of data points that correspond to things in the real world.

Big War, Big Data

This kind of large-scale logistics is, among other things, a massive math problem. While killer robots won’t be hitting the battlefield any time soon, the Army is optimistic that new technologies like artificial intelligence, machine learning, and big data analysis can help quickly crunch the numbers on supply.

The goal is predictive maintenance and logistics. That’s where an AI picks up on warning signs an unaided human might not see — an engine that chronically overheats, a battle that uses more anti-tank rounds than expected — and allows the humans to take initiative to forestall a problem before it becomes a crisis, be it by preemptively replacing a part or sending a supply convoy (maybe of self-driving trucks) before the frontline commander’s even asked for it.

“Know yourself, know your enemy, and don’t fear a hundred battles,” Perna said, citing Sun Tzu. “The key for me as a logistician and a sustainer is to be able to see ourselves….. not only with the data for today, but [using] artificial intelligence to help me make decisions for the future, [instead of] waiting for a piece of paper to show up that says you need 50 gallons of fuel or 5,000 gallons.”

That scales up all the way to an entire theater of war. “How fast do you think you think we can move hundreds of millions of gallons of fuel? Do you think it’s going to be after I get the report?” Perna asked. “The physics of logistics and sustainment will cause us to fail if we don’t get ahead.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.