Aerospace Sales To China Rise; Defense Exports To World Drop: AIA

Posted on

Breaking Defense graphic from AIA data

WASHINGTON: Despite President Trump’s push for more defense exports, sales of US military equipment fell last year, according to an authoritative report from the Aerospace Industries Association out today. Meanwhile, civil aerospace sales continue to rise — especially to the industry’s top customer, China.

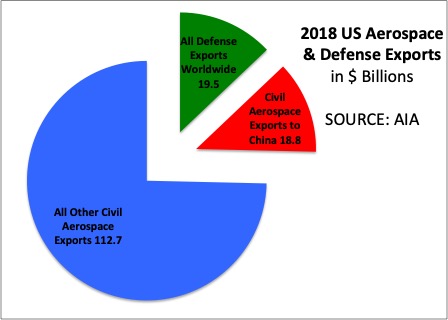

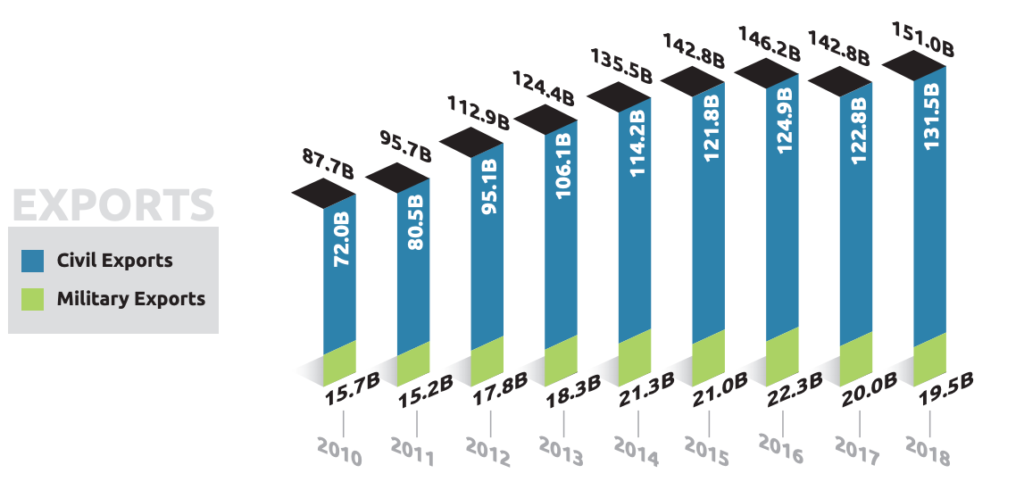

The US aerospace and defense industry exported a total of $151 billion in 2018, AIA calculated. Of that, $19.5 billion was military products, like fighter jets — well below the $22.3 billion peak of defense exports in 2016. But civil aerospace exports, such as airliners, kept rising, to $131 billion — of which $18.8 billion went to China alone. (For obvious reasons, the US does not sell military technology to China, so we can safely assume that all sales to China count as civil sales).

Breaking Defense graphic from AIA data

That means, in rough terms, that China’s airline industry is now almost as big a customer for US aerospace exports as every non-US military customer, combined. Give the current trends another year or two, and Chinese airlines probably will be buying more.

President Trump’s escalating trade war with China and his ongoing push for US defense sales overseas may shape those trends. But the underlying lesson of the AIA report is more about interdependence than competition.

Sure, AIA’s main message, as usual, is well-earned cheerleading for the aerospace and defense industry. Annual sales revenues have risen for eight years in a row, to almost a trillion dollars — $929 billion — of which exports are up to $151 billion. As a result, at a time when the US wrestles with ever-increasing trade deficits, aerospace and defense are running a trade surplus of almost $90 billion, the second-highest AIA has ever recorded.

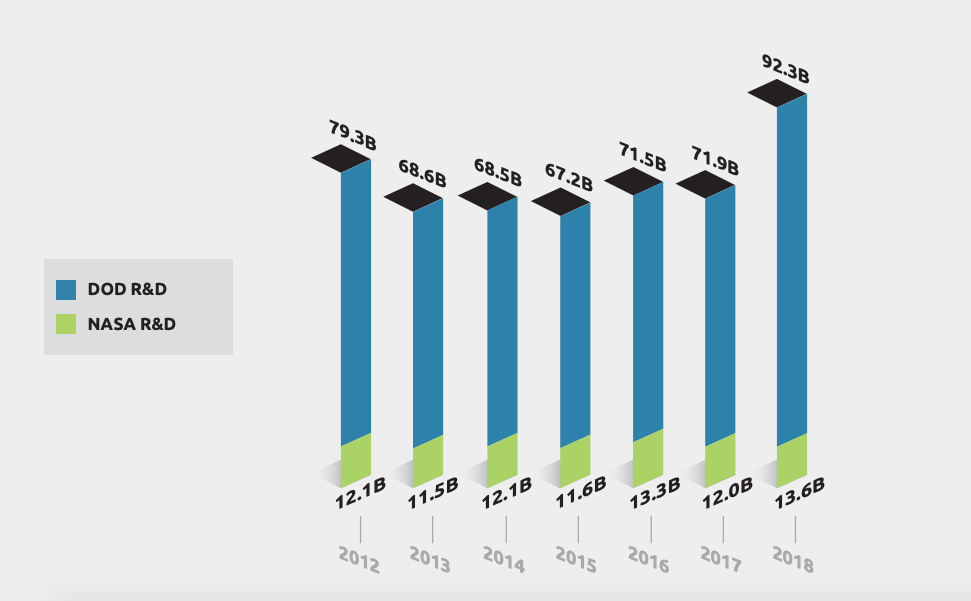

Perhaps the best news for America’s long-term competitiveness: federal R&D spending jumped more than 29 percent, after five years of stagnation. Defense Department and NASA together spend $92.3 billion on research and development in 2018, AIA calculated, compared to $71.9 billion the year before.

Now, industry R&D has been rising steadily for years, but at $17 billion in 2018, it’s still a fraction of government R&D spending. In stark contrast to information technology, where private sector investment and innovation have long since outstripped the government’s, federal investment is still crucial for the long-term health of the aerospace sector.

SOURCE: Aerospace Industries Association

But when it comes to short-term sales — the money that actually keeps the lights on and over 880,000 Americans employed at sites across the country — the balance is very different. Of those jobs, AIA estimates 42 percent are supported by national security-related work, 58 percent by commercial customers.

(These figures are just direct aerospace and defense employment at companies that make end-use items: Suppliers and subcontractors bring the total employee to 2.55 million).

When it comes to foreign sales, the balance tips even farther. Defense sales make up just 13 percent of all aerospace and defense exports. That’s the $19.5 billion in 2018 we mentioned earlier. By contrast, civil exports total $131.5 billion — almost seven times as much. And China is the No. 1 customer, buying $18.8 billion: That’s 14 percent of civil sales.

SOURCE: Aerospace Industries Association (used with permission)

Now, the aerospace industry hardly depends on China for its survival: If China somehow stopped buying all US aerospace goods tomorrow (highly unlikely), the industry would still run a sizable trade surplus. But with China as the industry’s No. 1 foreign customer — No. 1 with a bullet, given its voracious appetite for airliners — American aerospace manufacturers could be hurt badly by a trade war. What’s more, no matter how hard Trump pushes arms sales, no plausible increase in defense exports to US allies could make up for a collapse in civil exports to China.

The health of the aerospace and defense industry, both short-term and long-term, remains inextricably intertwined with federal spending and the defense budget in particular. But the broader industry is also increasingly reliant on maintaining healthy economic ties with Beijing in the face of rising international tensions and China’s internal economic stumbles.

We can’t count on international trade to eliminate the risk of war. That theory was thoroughly discredited in 1914, when intimately interdependent economies embarked on the most costly conflict in history at the time. But we can count on international conflict to undermine trade.

SOURCE: Aerospace Industries Association (used with permission)

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.