A Bridgehead Too Far? CSBA’s Aggressive, Risky Strategy For Marines

Posted on

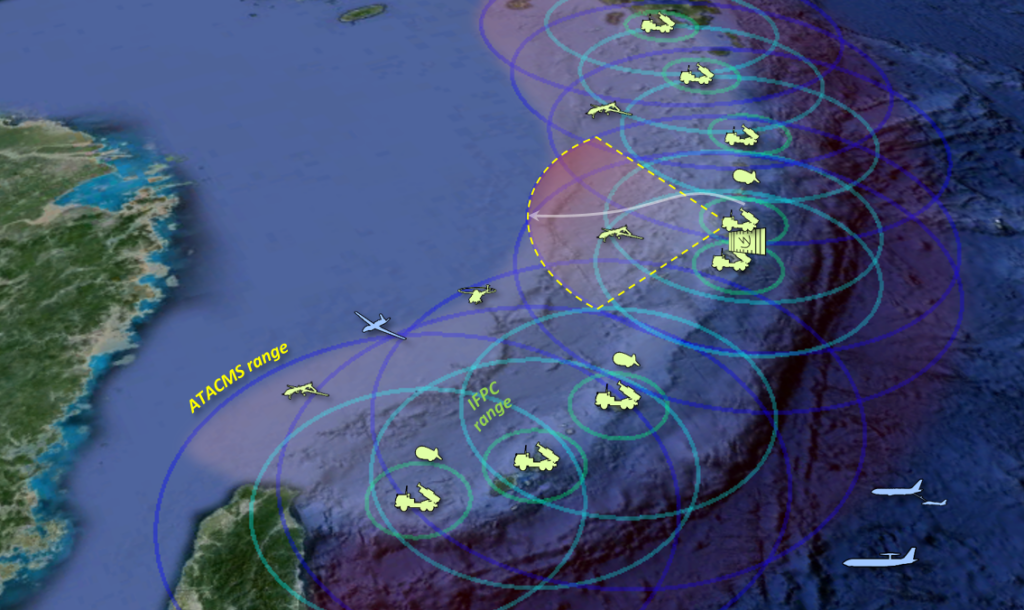

Land-based missiles could form a virtual wall against Chinese aggression (CSBA graphic)

UPDATED with Brig. Gen. Turner remarks on the report WASHINGTON: Marines are famously aggressive, but a new battle plan from a leading thinktank makes Iwo Jima look low-risk. The Center for Strategic & Budgetary Assessments’ proposed concept of operations is imaginative, exciting and more than a little scary:

F-35B

In a future war, rather than stay far out at sea until long-range strikes whittle down massed Russian or Chinese missile batteries, the Marine Corps should push ahead into the teeth of the defenses and establish outposts within enemy missile range. Trusting in camouflage, dispersal, and short-range missile defenses to survive, these Expeditionary Advance Bases would refuel raiding F-35B fighters and launch land-based missiles to take the adversary’s Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD) zone down from the inside.

CSBA’s idea is in line with the military’s increasing desire to blitzkrieg through weak points in A2/AD defenses, rather than laboriously bombard them from long range while our allies are overrun. (The Army calls this Multi-Domain Battle). But it’s far more aggressive and risky than any other such concept I’ve seen, because it calls for setting up static outposts inside the danger zone, rather than infiltrating mobile forces that stay constantly on the move. As Army Chief of Staff Mark Milley, never one to mince words, puts it: “On the future battlefield, if you stay in one place longer than two or three hours, you will be dead.”

So how does a stationary Expeditionary Advance Base survive not for hours but days?

Bryan Clark

“The idea is not to make it invincible, (but) to make the EAB a hard enough kill for a pretty low-value target,” said Bryan Clark, former senior aide to the Chief of Naval Operators and co-author of the study. By CSBA’s calculations, if the Marines spread out, dug in, and deployed new missile defenses like the Hyper Velocity Projectile (HVP) and the Army’s new Indirect Fire Protection Capability (IFPC), it would take an enemy 28 shots to guarantee a kill on any particular target.

What’s more, each advance base would have multiple targets, each dug in far enough apart a single warhead wouldn’t get them all: a refueling area for F-35Bs, a HIMARS missile launcher, an IPFC missile defense launcher, a howitzer battery firing HPVs, radars, a command post, bunkers for the Marines, etc. At some point, Clark argues, the Chinese or Russians would decide it wasn’t worth firing hundreds of missiles to wipe out a single reinforced company of a few hundred Marines, not when there were multiple such outposts to worry about on land plus Navy warships at sea.

The alternative to advanced land bases isn’t zero casualties, added CSBA co-author Jesse Sloman, a former Marine himself. It’s keeping the Marines aboard ship, where one lucky missile can kill hundreds.

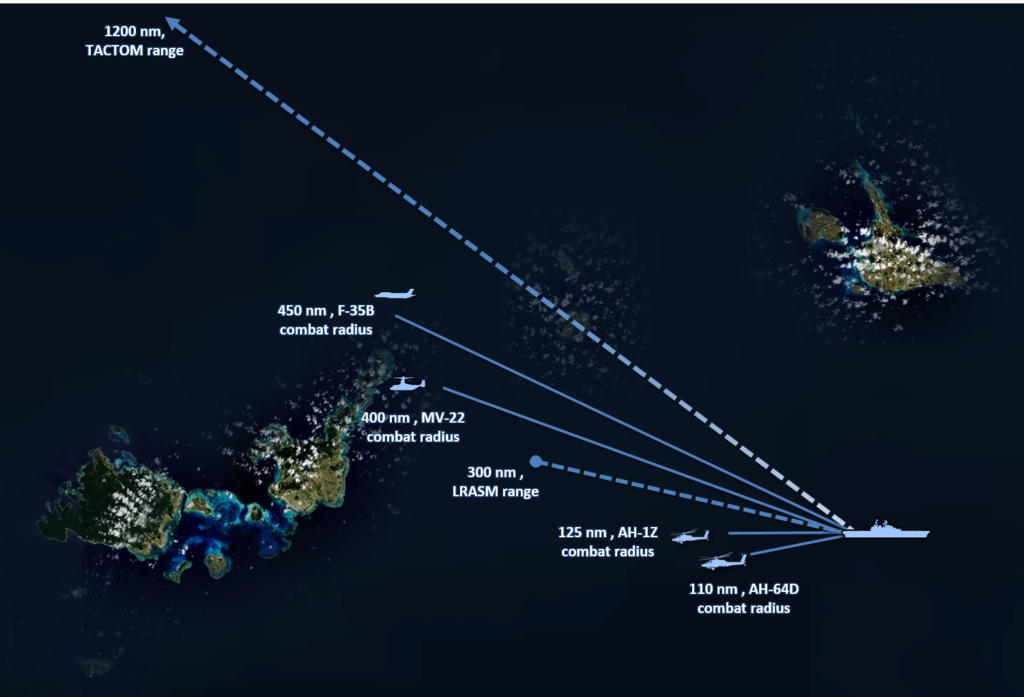

Chinese and Russian missiles could create a kill zone 200-300 nautical miles from shore, putting a premium on long-range aircraft (CSBA graphic)

The 300-Mile Problem

Some 80 nations now have anti-ship missiles, as do well-armed irregulars like Lebanese Hezbollah and the other Iranian-supplied group, Yemeni Houthis. While some of these weapons can strike targets over 1,000 miles away, these are rare, so Clark and Sloman advise that US fleets stay a still-impressive 300 nautical miles from hostile shores. Planes are faster, smaller targets than warships, so anti-aircraft missiles generally have less range, about 200 nm.

A 200- to 300-mile threat wrecks traditional amphibious tactics, in which warships to approach the beach before launching amphibious vehicles, which have limited seaworthiness. Even the Marines’ vaunted 40-knot Expeditionary Fighting Vehicle, cancelled for excessive complexity and cost, couldn’t cross such distances. The standard Marine Corps helicopters can’t cross such distances either — the AH-1Z gunship can only go 125 miles, for example — though the MV-22 Osprey tiltrotor can make 400 nautical miles and the F-35B jump jet 425.

MV-22 Osprey

So Clark and Sloman propose keeping the big ships (more or less) safely out at sea while deploying the Marines by long-range air and landing craft. The Osprey is particularly attractive, but its limited payload means it’s only able to land Marines, light equipment, and fuel bladders for forward-based F-35Bs. Clark and Sloman want to resume production of light-weight Internally Transportable Vehicles narrow enough to fit inside the Osprey. [UPDATE: The Marine Corps pointed out they are buying 144 Polaris MRZR-D light offroad trucks — 18 per infantry regiment — which can fit inside the MV-22 as well].

Even so, heavy equipment such as missile launchers will have to come on so-called surface connectors. There’s the lumbering LCU, which looks like a World War II relic; the speedy but fragile LCAC hovercraft; and, in future, the bizarre paddle-wheeled Ultra Heavy-lift Amphibious Connector (UHAC). Clark and Sloman also suggest modifying the catamaran Expeditionary Fast Transport (formerly the Joint High Speed Vessel or JHSV) with a ramp to offload amphibious armored fighting vehicles just off the beach. The combat vehicles themselves should be optimized for land operations, like the current Amphibious Combat Vehicle program, rather than trying for high-water speed, like the cancelled EFV.

Supporting all these long-distance operations will require more firepower from the fleet, both missiles and fighters. They want to upgrade amphibs with both offensive and defensive missiles fired from Vertical Launch System (VLS) tubes, space for which was carefully left in the current San Antonio-class LPD design. The Navy is examining upgunning amphibs as part of its Distributed Lethality concept to put offensive weapons on ships currently designed for only self-defense.

Jesse Sloman

Clark and Sloman also want way more Joint Strike Fighters. Currently, a three-ship Amphibious Ready Group (ARG) has two smaller amphibs and one big deck LHA or LHD which can carry just six fighters. That’s not enough to escort all the V-22s, to protect multiple Expeditionary Advanced Bases, or to take advantage of the forward refueling points the EABs provide. (Attack helicopters lack the necessary range, they say, though they would protect the fleet from fast attack boats). So the CSBA scholars want to increase the ARG’s F-35B contingent from six to 10-20, depending on the mission.

That larger air contingent, in turn, requires a larger ARG. Clark and Sloman suggest adding a fourth ship, a small-deck L(X)R, to help carry helicopters so the big-deck LHA/LHD can focus on jet fighters, which only it can handle. They prefer LHAs without welldecks to devote maximum space to aviation, and in the long term, they’d like to replace the LHA with a light aircraft carrier (CVL) able to handle conventional take-off and landing aircraft like the E-2D Hawkeye scout and the EA-18 Growler jammer. All told, their plan would add nine L(X)Rs to the Navy’s shipbuilding plan and replace four planned LHAs with more expensive CVLs, at a total estimated cost of $21 billion over 30 years.

“You need to go to this four-ship ARG,” said Clark. “That’s inexorable, we really couldn’t come up with another way” to execute the concept of operations on a global scale. That said, the cost of the Navy’s 30-year plan would only increase by 3.5 percent.

The Marines would also need to buy more F-35Bs, HIMARS missile launchers, and anti-ship-capable ATACMS missiles, as well as Army-only systems like IFPC. But nothing in the concept would require some radical breakthrough technology, Clark and Sloman argued. It’s all in the realm of the achievable — it’s just risky.

Brig. Gen. Roger Turner

General Turner’s Take

At the report’s official rollout this evening, the director of the Marine Corps’ Capabilities Development Directorate praised the CSBA concept — with a couple of reservations.

“This is a well thought out and well-supported study,” said Brig. Gen. Roger Turner. “Leaders in the Marine Corps and the Navy support the general conclusions.”

The fundamental point of agreement: Long-range missile threats require the fleet to operate very differently. “There’s broad recognition in the (Navy) Department that the current paradigm, of a naval force that’s optimized for power projection capability in a benign environment, is kind of a relic,” Turner said. “That’s no longer a viable concept and that’s going to have to change.” Rather than counting on the Navy to rule the waves and get the Marine Air-Ground Task Force (MAGTF) ashore, he said, “we’re going to have to help the Navy in the sea control fight, so the MAGTF’s going to have to start to fight much earlier.”

LHA-6, the USS America

Nevertheless, Turner was skeptical of CSBA’s suggestion that, to muster sufficient airpower for long-range war, the Navy should move to big-deck amphibs, or even light aircraft carriers, without well decks from which to launch landing craft and amphibious vehicles. While the Marines could form an aircraft-heavy task force if great power war was imminent, he said, during day-to-day operations the Amphibious Ready Group must be equipped for everything from disaster relief to hostage rescue. While dozens of amphibs might make up a wartime fleet, offering plenty of opportunity for each to specialize, in peacetime high demand for amphibs means individual ships often operate alone, so each ship needs the full range of capabilities — including a well deck.

While the great power war scenarios that drove the CSBA study are the most important mission, Turner emphasized, they’re not the only one. “We have commitments across the range of military operations,” he said. “We don’t have the luxury of being able to completely purpose-build the Marine Corps or the Navy for a single threat scenario.”

On the other hand, Turner was far more comfortable than me with the study’s proposal for Expeditionary Advance Bases inside enemy missile range. Remember, he told me when I raised the risks, that the Marine Corps never operates alone.

Tern, DARPA’s proposed ship-launched drone.

“All of these operations need to be viewed in context of what the joint force capability brings,” Turner said. “Certainly there are enemy capabilities out there that are pretty difficult to deal with, but we’re pretty confident in our own joint capabilities.” Satellites, drones, bombers, cruise missiles, and cyber attacks should be able to detect, defeat, and destroy enough Anti-Access/Area Denial systems that the Marines can penetrate the A2/AD zone. “We’re not ready to cede those threat rings and say…we can’t operate inside those,” Turner said.

That said, operating inside the danger zone does require careful preparation. “We have to make sure that once we do put forces ashore that they’re going to have the requisite force protection,” Turner said. In particular, he said, “we’re going to need to invest in air defense.”

“It does represent a paradigm shift for us,” Turner said, “and we are going to make investments to change the composition of the force to make it more survivable.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.