70-Year-Old M113s: The Army’s Long March To AMPV

Posted on

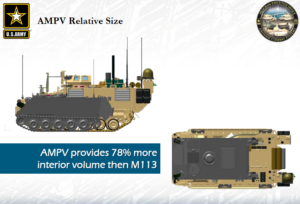

The future Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle (AMPV) compared to the M113 it will replace

HUNTSVILLE, ALA: The lethally under-armored M113 “battle taxi” will celebrate its seventieth birthday before the Army replaces it with a new Armored Multi-Purpose Vehicle.

Under current plans — which assume spending levels well above those allowed by the Budget Control Act (aka sequester) — AMPV production at contractor BAE Systems will max out at 180 vehicles a year, Col. Mike Milner, the AMPV program manager, said today at AUSA Global, the new and improved version of the old AUSA Winter conference. That’s enough vehicles to modernize 1.3 armored brigades a year. With 12 such brigades in the Army, the last would replace its M113s in the “late 2020s,” Milner said.

But the Army has another 1,900 M113s in other formations. Their replacement is currently undecided. Whether it’s AMPV or something else, however, there’s no way it will be finished before 2030.

Army M113 in Vietnam

That’s seven decades after the M113 entered service in 1960. Even in Vietnam, it was considered so vulnerable to mines that many soldiers preferred to ride on top, with the whole vehicle between them and the blast, rather than risk being pulped inside. In the age of the roadside bomb, many commanders in Iraq refused to let their M113s off-base. That problem won’t get fixed for a decade or more for most Army units.

Across the board, “production rates that we’re currently funded to in the combat vehicle modernization portfolio are not optimal rates,” said Brig. Gen. David Bassett. As Program Executive Officer for ground combat systems, Bassett oversees not only AMPV but M1 Abrams tanks, M2 Bradleys, and Paladin howitzers. His staff’s analysis shows major potential cost-efficiencies at higher production rates, he said. Army budgeteers are fully aware of the benefits, but they don’t have enough money.

Those funding limits leave a big question mark over what will replace M113s outside the armored brigades. AMPV is obviously a leading candidate, but rear-echelon units might not require the same performance. “There are multiple studies out there for echelons above brigade,” Milner said. One study for the House Armed Services Committee done in February found many such units have similar requirements to AMPV, but they are not necessarily identical. The Senate Appropriations subcommittee on defense has asked for another.

This potentially opens the door to General Dynamics, which refused to enter its eight-wheel-drive Stryker vehicle in the AMPV competition, arguing the Army had levied unreasonably high requirements for cross-country mobility that no wheeled vehicle could meet.

“There was never a specification for it to be a wheeled or tracked vehicle,” emphasized Milner. “The proposal that was selected did happen to be a tracked solution, but it was not required to be one.”

The problem with that answer is the Army did require the AMPV to be able to keep up with frontline elements of the armored brigade, and those are tracked vehicles. In fact, the plurality are M2 Bradley troop carriers, from which the winning AMPV design derives. The upgraded M109 Paladin howitzer will also have a Bradley power train and suspension. Overall, choosing BAE’s design over General Dynamics’ allows 75 percent of the armored brigade’s combat vehicles to share the same automotive components. That eases maintenance and logistics, as well as guarantees they can keep up with one another.

The problem with that answer is the Army did require the AMPV to be able to keep up with frontline elements of the armored brigade, and those are tracked vehicles. In fact, the plurality are M2 Bradley troop carriers, from which the winning AMPV design derives. The upgraded M109 Paladin howitzer will also have a Bradley power train and suspension. Overall, choosing BAE’s design over General Dynamics’ allows 75 percent of the armored brigade’s combat vehicles to share the same automotive components. That eases maintenance and logistics, as well as guarantees they can keep up with one another.

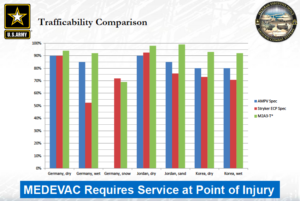

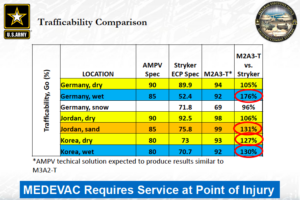

Critics argue that AMPV is a support vehicle that doesn’t need the exact same performance as a frontline war machine. It’s true, Bassett admitted, that if you look at the entire mission profile, a Stryker can go almost everywhere a tracked AMPV can. But that almost is a killer — literally.

Army models show a Stryker ambulance would perform worse than a Bradley variant on many kinds of rough terrain, especially soft ground like sand, rice paddies, or mud. It’s a matter of simple physics: Tracks distribute a vehicle’s weight over a much wider area than wheels, so they’re less likely to bog down, the same way boots do better in mud than heels. If an armored ambulance can’t get to the front line, wounded soldiers are more likely to die.

That armored ambulance is just one variant of the AMPV, however. It would evacuate wounded soldiers back to a forward aid station just behind the lines, often set up from a sister AMPV, a mobile surgery called the medical treatment vehicle. Other AMPV variants include a mortar carrier, providing close-in fire support; a command vehicle; and a general purpose carrier for supplies and soldiers.

The Army doesn’t want to compromise on cross-country performance of any of these variants. With General Dynamics and other wheeled-vehicle advocates lobbying hard on the Hill, that decision will remain one for vigorous debate.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.