4,817 Targets: How Six Months Of Airstrikes Have Hurt ISIL (Or Not)

Posted on

[UPDATED with McCain comment] The war is escalating. But what have six months of airstrikes against the self-proclaimed Islamic State actually achieved so far?

Last week, Jordan launched its retaliation against the Islamic State for burning a Jordanian pilot alive. Yesterday, we learned ISIL had murdered hostage Kayla Mueller. This morning, President Obama formally proposed a new Authorization for the Use of Military Force (AUMF) against ISIL, eliciting ambivalent comments from Congress (more on that below). The crucial question: how much leeway to leave for the future use of US ground troops.

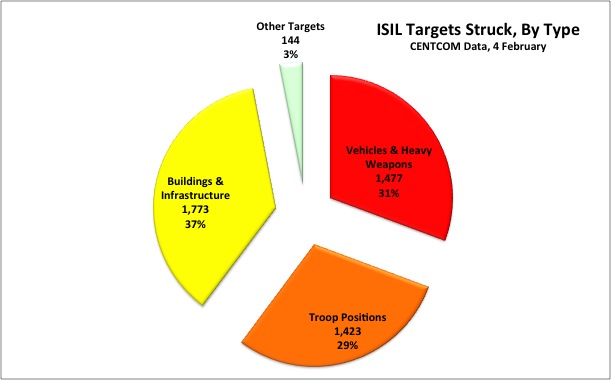

This afternoon, US Central Command (CENTCOM) released its most detailed data yet on what the current airstrikes-only approach has accomplished so far. (We’ve analyzed earlier data here, here, and here). It counts 4,817 targets damaged or destroyed as of February 4th by the US and its coalition partners. The list is broken down into 28 categories, from 752 “fighting positions” — e.g. foxholes — to seven items of “communications equipment.” We thought we’d aggregate that a little for you:

One fact leaps out: This is close air support against enemy ground troops, not the surgical strikes against strategic targets that the Air Force was born for. Almost two-thirds of targets struck are troops, forward positions, and vehicles; just one-third are buildings and other fixed infrastructure. This is an imperfect indicator, since some buildings may be temporary staging positions close to the front line, and some troops may be hit far to the rear. Overall, though, the 2:1 ratio in targets by type indicates the air campaign is emphasizing ISIL’s forward fighting forces — what pilots once derided as “tank plinking” — rather than its rear support structure.

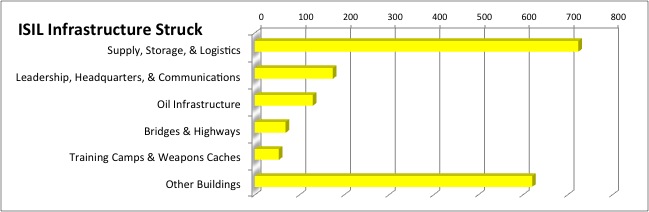

Of course, the Islamic State — like the Taliban and Iraqi insurgents — doesn’t have many strategic “nodes” to strike. While attacking ISIL’s oil infrastructure has hurt the terrorists’ finances, for example, it only accounts for 130 targets struck, less than three percent of the total. Attacks on bridges and roads likewise amount to only 69 targets (1.4 percent); there aren’t many of these “air interdiction” targets probably because ISIL doesn’t move in large, road-bound formations like Rommel trying to reinforce the Normandy beaches after D-Day, maneuvers which could be seen and stopped by Allied airpower.

The US Air Force — and before that the Army Air Corps — historically wants to hit deep behind enemy lines. Its institutional preference is to cut off the head of the snake, not to deliver body blows. The 2003 “shock and awe” airstrikes were perhaps the pinnacle of this approach. Since 2003, however, with US ground troops engaged by guerrillas who had no headquarters, factories, or other infrastructure to target, the Air Force has gotten very good at close support. (The Navy and, even more so, the Marines never had the same institutional ambivalence about the mission).

The difference this time is it’s not US ground troops that the airstrikes are supporting: It’s local allies like the Kurdish pershmerga and Iraqi army. In some ways we’ve gone full circle back to 2001, when a massive American air effort supported Northern Alliance ground troops against the Taliban. The question is whether the 2001 model can work against the Islamic State.

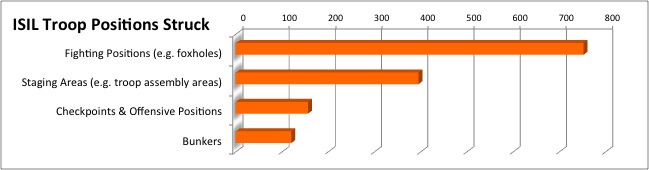

The ISIL offensive has certainly stalled. Last year’s lightning advances gave way to local stalemates and a meatgrinder battle for Kobani, where ISIL troops massing to attack the Kurds on the ground made themselves easy targets for the Americans in the air. Overall, the air campaign has hit some 395 “staging areas” where ISIL fighters were gathering.

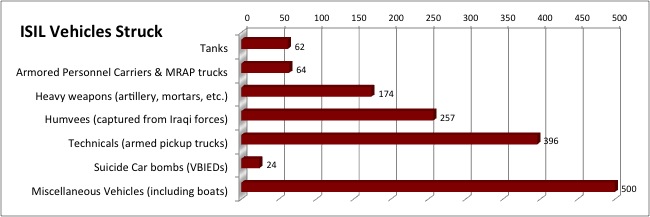

While ISIL captured parking lots full of sophisticated military vehicles from the Iraqi military, shortfalls in training and supplies mean it still relies on pickup trucks with weapons — but no armor — hastily bolted on: 396 of these “technicals” were struck, compared to just 62 tanks. Looking at the target list overall, ISIL largely lacks heavy weapons to support its fighters’ advance, armored personnel carriers to move them forward under fire, or tanks to spearhead the advance. Its lightly armed fanatics can overrun demoralized enemies like the Iraqi army or the moderate Syrians, but against determined resistance they end up replaying the Western Front of World War I.

But stalemating ISIL is a long way from rolling it back. Defense is easier than offense, but only offense can force an end to fighting, Clausewitz famously wrote. So far, though, the Iraqi security forces lack the morale to take the offensive, the Kurds lack the heavy weapons, and the moderate Syrian rebels lack both. They need US training, equipment, and air support to advance. But do they need US troops?

Currently, the US ground presence in the region is largely limited to rear-area training in Iraq. Senate Armed Services chairman John McCain called months ago for “more boots on the ground… in the form of forward air controllers, special forces and other people like that.” Small numbers of such specialists can direct airstrikes to precise and devastating effect, as they did in support of the Northern Alliance after 9/11, and arguably they are the crucial piece of our 2001 success in Afghanistan that’s missing from the Middle East today.

The Authorization for the Use of Military Force that President Obama proposed this morning wouldn’t rule such limited ground forces out. The accompanying press release envisions special operations raids, search-and-rescue for downed pilots, and miscellaneous supporting roles “where ground combat operations are not expected or intended.” The text of the AUMF itself, however, only excludes “enduring offensive ground combat operations.” That’s a studiedly ambiguous phrase with loopholes large enough to drive a tank division through.

[UPDATED: After apparently taking most of the day to digest the president’s proposal, McCain came out with a scathing statement on the draft AUMF. “I am pleased that the President has finally taken the important step of proposing an AUMF to the Congress,” McCain said. “However, I have deep concerns about aspects of this proposed authorization, including limitations placed on the constitutional authority of the commander-in-chief, the failure to articulate an objective for the use of military force, and a narrow definition of strategy that seeks to separate the fight against ISIL from the underlying conflict in Syria and the Assad regime’s responsibility for this growing terrorist threat. This is a recipe for failure.”]

McCain’s counterpart Mac Thornberry, chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, said with his typical even-handedness that the President had taken “the right step” by asking for congressional authority, but the way Obama had done so raised “concerns,” especially “why he is seeking to tie his own hands by limiting authority that he’s already claimed.” The top Democrats on the two committees, Sen. Jack Reed and Rep. Adam Smith, both supported the president’s proposal — although Reed added it was “overdue.”

“Now,” Reed said, “it is time for Congress to debate, refine, and ultimately vote on a new AUMF.” The challenge will be aligning political realities with military ones.

Updated 8:30 am Thursday with McCain comment.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.