2018 Forecast: Can the Navy Say No?

Posted on

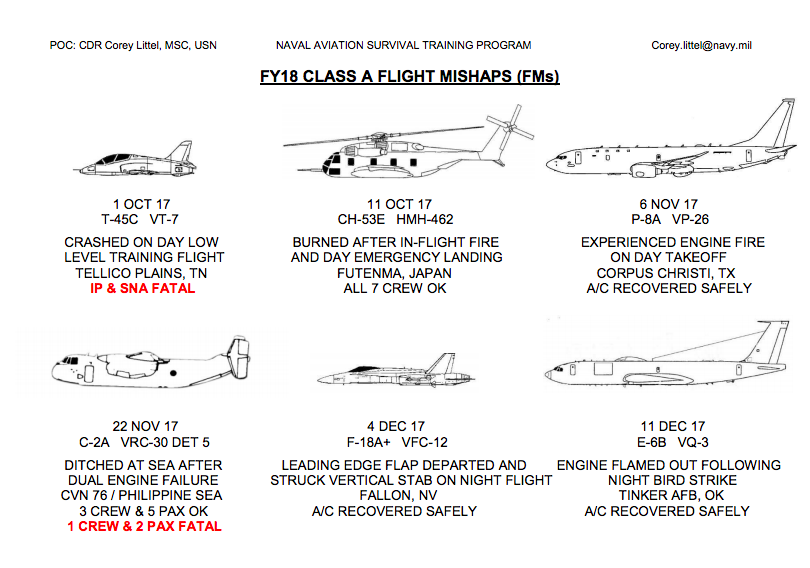

The Navy has suffered 6 Class A” mishaps since Oct. 1st

WASHINGTON: In 2017, the Navy and Marine Corps hit the wall, with an string of deadly accidents on the sea and in the air. In 2018, we’ll see whether the overstressed sea services start saying “no” to missions.

Navy Secretary Richard Spencer discusses his Strategic Readiness Review with reporters.

That means battles both in the Pentagon and on the Hill. The newly named Secretary of the Navy, Richard Spencer, seems to be charting a collision course with joint commanders, who he says have run the services ragged with too many missions, and with the Goldwater-Nichols Act of 1986, which gave joint headquarters preeminence over the four armed services in many areas. In recent years Congress and the Pentagon have restored some of the service chiefs’ authority over weapons acquisitions, but they haven’t questioned the basic balance of power set in law some 31 years ago. Now the Strategic Readiness Review which Spencer commissioned has put changing Goldwater-Nichols on the table.

How to make the case for change? “We’ll start every conversation with 17 dead sailors,” Spencer pledged in September. But 17 deaths is just the beginning. While Spencer was talking specifically about two deadly surface ship collisions this summer, transport aircraft crashes killed 19 Marines in July and August. In response, the Commandant, Gen. Robert Neller, ordered rolling safety stand-downs at all Marine aviation units.

This summer was just a particularly lethal spike in a long-running trend. Crashes of a C-2 transport and a T-45 trainer killed five more Navy personnel just since fiscal year 2018 began on October 1st. Three naval aircraft have been lost in accidents since Oct. 1, another three damaged.

The USS McCain heads for Shanghai after a collision that killed 10 sailors.

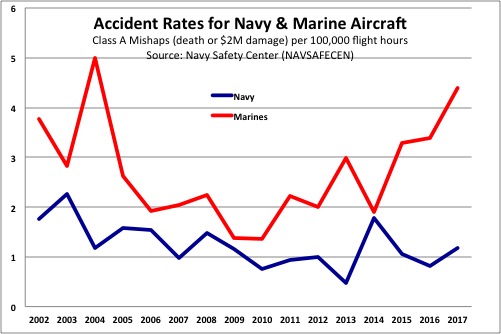

In fiscal 2017, Navy aircraft suffered 10 Class A Mishaps involving permanent disability, loss of life, or more than $2 million in damage. The Marines, with a much smaller air fleet, suffered another 10. Long-term, both services have seen rising accident rates ever since 2013, when the Budget Control Act abruptly cut funds for training and maintenance. The Marines in particular have seen their accident rate — which has long been higher than the Navy’s — more than double over the last two years.

As costly as these accidents are, and as devastating as these deaths have been, the biggest potential catastrophe is a force unready for combat. Early in 2017, the sea services admitted that 53 percent of all naval aircraft were grounded for maintenance, rising to 62 percent for strike fighters and 74 percent of Marine Corps F-18 Hornets. As for surface ships, both a former deputy secretary of defense and a panel of retired captains have publicly argued that the recent series of accidents — not just the two fatal ones — shows a force struggling with basic seamanship, let alone the complex skills required to fight an enemy fleet. Meanwhile the third pillar of the Navy, the submarine branch, has avoided deadly accidents but still has an unprecedented proportion of its boats idled awaiting maintenance: Ready submarines are consumed by day-to-day missions for the joint commanders, leaving few boats in reserve to “surge” in a major war.

Time & Money

So what do the Navy and Marine Corps need? The most precious commodity is time: time to catch up on training, time to clear up the maintenance backlog. But time is finite, and every day spent getting ready is one less day out doing missions. The services’ concern for readiness — particularly for major wars — conflicts directly with the theater commanders‘ need for naval presence. The current Pentagon process effectively gives the joint commanders a blank check for how heavily forces are committed around the world, with little provision for the services to throw a yellow flag and say “too much.” That’s the system Sec. Spencer seems ready to challenge.

Money would help too, of course. More money for maintenance and training would help readiness, but, less obviously, so would more money for modernization. Buying new ships and aircraft could let the Navy and Marines retire aging, unreliable equipment, which drags down readiness because it’s down for maintenance too often.

The damaged destroyer USS Fitzgerald pulls into Yokosuka, Japan after colliding with a commercial ship. Seven sailors died.

Or you could use the new ships and planes to increase the size of the force. Growth improves readiness by spreading the workload over more units, giving each more time for training and maintenance. (Of course, that assumes that the workload doesn’t go up too, and that training and maintenance funds go up proportionately instead of being spread thinner over the larger force). The Chief of Naval Operations himself, Adm. John Richardson, said that building more ships would help prevent future accidents, because with more ships at work, none of them would be worked as hard.

Building a bigger fleet is a long-term solution, however, with estimates ranging from 18 years to about 35. And despite President Trump’s encouraging rhetoric, the administration struggled to add just one new ship to the 2018 budget — which Congress hasn’t yet managed to fund, even as we start the second quarter of the federal fiscal year.

For now, then, the Navy and Marine Corps have to improve readiness without a larger force or even additional training and maintenance money. That means their only option is to take on fewer missions — which is why Sec. Spencer has to challenge Goldwater-Nichols.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.