1914 Redux? Growing Asia-Pacific Tensions Demand New US Strategy

Posted on

American Secretary of State Rex Tillerson is paying his first visit to Asia this week. Just before he left, Acting Assistant Secretary of State Susan Thornton told reporters the Trump Administration “will have its own formulation” of the Pacific pivot, or the rebalance to Asia declared by the Obama Administration.

“Pivot, rebalance, etcetera — that was a word that was used to describe the Asia policy in the last administration. I think you can probably expect that this administration will have its own formulation. We haven’t really seen in detail, kind of, what that formulation will be or if there even will be a formulation,” she said.

In this timely op-ed, Maj. Paul Smith, who works in the J-9 of U.S. Pacific Command but is, of course, writing in a personal capacity, compares today’s international security situation to that preceding World War I and sees worrying parallels. He calls for a reassessment of our strategy toward China. Read on. The Editor.

The global environment today eerily resembles that of Europe in the early twentieth century, when a rising tide of nationalism swept through the continent. That nationalism led to increased trade competition, networks of intertwined and complicated alliances and social and political ferment that sparked a war that eventually spread to engulf much of the world in the flames of World War I.

Are we headed towards another global conflict? If so, then where? Most importantly, can this crisis be averted?

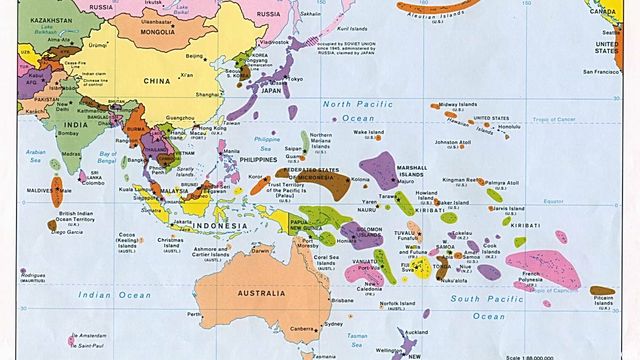

The geopolitical climate most similar to pre-war Europe lies within the Asia-Pacific. This region consists of a highly complex web of interwoven treaties and alliances, is home to the world’s most formidable rising power, and has historical flashpoints, that if triggered, could lead to armed conflict. These same issues had been present in Europe for years before the assassination of Archduke Ferdinand began the chain of events that eventually plunged, first Europe then much of the world, into the Great War.

In the early 1900s a general sense of calm had swept over Europe in the 40 years of peace that followed the Franco-Prussian War. Many Europeans felt that with increased financial and economic interdependence, war had become too unprofitable for either side and was therefore not likely. But Germany, now united, used this period to increase its political, economic, and military clout. That led to its increased stature amongst the traditional European powers, but German nationalism demanded global parity.

As political tensions rose across Europe, Germany allied itself with the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Italy to limit the likelihood of attack by other European nations. This was followed immediately by France, Russia, and the United Kingdom entering into an alliance. That led to increased German fears of encirclement and tensions on the European continent mounted. With the existence of these two opposing blocs, a war between two nations would mean war between them all.

Amidst the political wrangling between nations each alliance grouping sought to balance the power of the others, triggering a European arms race. Between 1908 and 1913, Germany increased its defense spending from $286.7 million to over $460 million. As German military clout increased, the rest of Europe rushed to restore the balance of power on the continent by vastly increasing their militaries.

Even amidst the increase in arms, philosophers and scholars continued to discuss the end of war as they knew it. Unfortunately for the millions of young men that would soon be engaged in battle they were right, not about the end of war, but that war as it had been known would change drastically unleashing violence as never seen before. European nations’ armies swelled in both numbers and lethality as the dawn of the industrial age brought with it innovative and terrifying weapons which would soon be unsheathed on the field of battle.

As Europe divided itself into heavily armed rival treat blocs, several long simmering issues grew to become potential flashpoints. France was unhappy with the treaty that ended the Franco-Prussian War and wanted to regain control of the Alsace-Lorraine region. The Austro-Hungarian Empire was in decline and the empire began fracturing along ethnic lines. The traditional great European powers were also frustrated by Germany’s ascent, which set the scene for the Thucydides Trap — the likelihood of conflict between a rising power and a currently dominant one.

Then shots rang out in Sarajevo on June 28, 1914. Archduke Ferdinand and his wife Sophie died. Austria declared war on Serbia. Within weeks all of Europe was embroiled in the first truly global conflict, World War I.

Troops go over the top in World War I.

Following the almost unimaginable destruction and loss of life wrought during World War I and World War II, the international community was determined to prevent another cataclysmic global confrontation. The United Nations was formed. The Bretton Woods monetary system was built. NATO was created. Nearly three quarters of a century later their efforts have been largely successful. In that time, America has risen to be the world’s sole superpower and has, with several allies, crafted a rules-based international order that continues to foster that peace.

One hundred years after the final shots of World War I rang out, there are several potential challenges to that peace lurking on the wavetops in the Asia-Pacific, a highly diverse and potentially volatile region containing a nuclear-armed rogue nation, the world’s three largest economies; the United States, China, and Japan, and historical rivalries that predate the liberal rules-based international order. Nationalism, coupled with rising competition for natural resources, have led to a 400 percent increase in military spending and an increasingly complex web of bilateral and multilateral treaties over the past 30 years, mirroring continental Europe in the years prior to the outbreak of WWI.

As power shifts, the question that must be addressed is whether or not America is willing to yield to a multi-polar world. It seems that the groundwork is being laid within the Asia-Pacific region for another Thucydides Trap. Several potential protagonists within the Asia-Pacific could challenge the United States’ global hegemony in the years to come. But none bears a closer resemblance to Germany following the Franco-Prussian War than does China.

Chinese economic strength first drew the attention of the established Western powers after it adopted a market economy in the late 1970s. China emerged from the 2008–2009 financial crisis relatively unscathed, in stark contrast to Europe and America. Their rapid recovery led to increased demand for parity in international affairs, challenges to the rules-based order, and what some consider attempts to establish a regional sphere of influence within Asia. To advance its presence on the world stage, China continues peaceful endeavors, such as its establishment of the Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank (AIIB) and other economic investments as part of its One Belt, One Road initiative. In a manner eerily reminiscent of Germany in the early 1900s, China is now using the gains from its industrial revolution to turn its economic and industrial clout towards arms production.

Chinese artificial island

China’s People’s Liberation Army (PLA) has begun reorganizing to increase its effectiveness, invested in power projection platforms to extend its military reach, and focused heavily on advanced technological platforms such as unmanned aerial vehicles and stealth fighters. China has also undertaken massive land reclamation efforts in the South China Sea and, in recent months, has begun construction of military infrastructure on several of these new fake islands. This build up may soon enable China to militarily control a transit route through which approximately 30 percent of the world’s maritime trade passes, including about $1.2 trillion in ship-borne trade bound for the United States.

Several Asia-Pacific nations have begun to respond to the potential threat posed by the rising dragon that is China. To balance Chinese expansionism, East Asian nations are designing new defense cooperation agreements and are increasing their defense spending. The threat posed by China has even helped to overcome historical differences. Most recently, Vietnam has begun purchasing arms from the United States. Japan has reversed security laws in place since the end of World War II to allow its military to become more involved regionally, and it is crafting bilateral defense agreements with Indonesia and Vietnam. This response to China has not only been militarily focused. The Philippines challenged China’s maritime claims in the South China Sea at the International Tribunal of the Permanent Court of Arbitration at The Hague. The tribunal ruled overwhelmingly in favor of the Philippines, utterly rejecting Chinese claims to what it calls the Nine Dash Line.

The Asia-Pacific is home to five of America’s seven mutual defense treaties; the Philippines, Thailand, Republic of Korea, Japan and Singapore. A majority of these nations are embroiled in some level of opposition to China. In spite of the tribunal’s ruling, China has shown no signs of slowing down the build-up of man-made islands in the South China Sea. Japan and China have long argued over who owns several islands in the East China Sea. South Korea has asked the United States to deploy advanced missile defense equipment which led to Chinese restrictions on trade with the Republic of Korea. Recently, China delayed a ship carrying Singapore Armed Forces’ equipment as it returned from a training exercise in Taiwan. None of these actions in and of themselves would seem likely to cause a global conflict, but the United States is bound by our mutual defense treaties to support our allies. As tensions rise in the Asia-Pacific, it is difficult to determine what spark might ignite the powder keg.

The Asia-Pacific is home to five of America’s seven mutual defense treaties; the Philippines, Thailand, Republic of Korea, Japan and Singapore. A majority of these nations are embroiled in some level of opposition to China. In spite of the tribunal’s ruling, China has shown no signs of slowing down the build-up of man-made islands in the South China Sea. Japan and China have long argued over who owns several islands in the East China Sea. South Korea has asked the United States to deploy advanced missile defense equipment which led to Chinese restrictions on trade with the Republic of Korea. Recently, China delayed a ship carrying Singapore Armed Forces’ equipment as it returned from a training exercise in Taiwan. None of these actions in and of themselves would seem likely to cause a global conflict, but the United States is bound by our mutual defense treaties to support our allies. As tensions rise in the Asia-Pacific, it is difficult to determine what spark might ignite the powder keg.

Rising Chinese nationalists use their dynastic past to call for expansion on the global scale. They demand control of the South China Seas based on the Nine Dash Line, and the Chinese state media incites national pride to help mask issues at home. That same fervor is a double-edged sword, however. As the government seeks to build national pride, actions that are viewed as an embarrassment in the realm of international relations may incite the populous to rally against the Chinese Communist Party (CCP). For the CCP elite, a conflict may be the lesser of two evils since political accommodation could result in the collapse of the government at the sword of nationalism.

As we near the 100th anniversary of America’s entrance into World War I, the stage appears set again for another global reordering, with consequences that could affect the world either through military action, or indirectly, through a disruption of the rules-based international order. Are we destined for World War III? What role should the United States play in addressing these issues? Modern history has demonstrated that when the United States adopts a nationalistic or isolationist foreign policy, the likelihood of war increases. While past conflicts primarily focused on the European continent, the similarities between the early 20th century European political climate and today’s Asia-Pacific make it easier to imagine a clash here between China and the United States. Despite what seems to be the popular allure of “America First”, the United States cannot afford to withdraw within our borders, or reduce the strength of our alliances. A revised strategy is required to address the rising tensions in the Asia-Pacific.

Any policy regarding China must fully incorporate the social theories that apply within their society, the global trends likely to affect the region, and the elements available to the United States to effect change. America’s Rebalance to the Pacific (which Breaking Defense likes to call the Pacific Pivot) is escalating tensions between the U.S. and China by ignoring the rising nationalism within China. That nationalistic narrative focuses on China as a victim, is exacerbated by troop buildups, increases in military training with other regional actors, and building rhetoric that paints the Chinese as adversaries. Given the current perception that the United States is looking to contain China and prevent its ascension as a multipolar world power, it is time to reconsider the current U.S. strategy.

A multi-pronged approach implementing several elements of national power is necessary to encourage China to become a world power that abides by international rules and laws. The most powerful tool available to the U.S. is its economy, which should be leveraged through international trade agreements. Despite the apparent death of the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP), a potential replacement agreement should be developed with China as a core member. Including China in a multinational agreement has a larger effect than just increased trade; it would reduce tensions in the Asia-Pacific region by increasing the reasons for China to adhere to the current rules-based international order.

Paradoxically, increased military to military engagement between the U.S. and China is vital. Currently, there is more mysticism than realism towards Chinese military capabilities, due to the limited interactions between our armed forces. By increasing the amount of contacts and familiarity between the two forces it becomes more difficult to cast the other as a villainous aggressor. More focus on joint training events such as the Rim of the Pacific Exercise (RIMPAC), the world’s largest maritime exercise with participants from over 20 nations including the U.S. and China, will help reduce the likelihood of conflict erupting due to miscommunication. Additionally, increased contact could reduce the virulence of Chinese nationalists looking to foster the image of China as a victim of the West.

Strategies that are not willing to adopt a less adversarial approach to China in the Asia-Pacific feed directly into a growing Chinese nationalism that could spark existing tensions between the U.S. and China into the flames of war. Only a strategy leveraging the U.S. economy and military to build stronger and broader ties between China and America will defeat growing Chinese nationalism and reduce tension in the Asia-Pacific.

The views expressed in the op-ed are those of Maj. Paul Smith and do not necessarily reflect the views of Pacific Command, the Navy or the Defense Department.

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.