$125 Billion Savings? Not So Fast, Say Experts, DoD, Rep. Smith

Posted on

WASHINGTON: Want to save $125 billion by slashing Pentagon “waste”? Not so fast. If you take a closer look at the much-touted Defense Business Board study proposing those cuts– which was published in 2015 but went viral after Monday’s Washington Post story saying the Pentagon had “burie[d]” it — and talk to experts, officials, and the top House Democrat on defense policy, the savings turn out to be less of a slam-dunk than advertised.

Rep. Adam Smith

“I don’t necessarily think the report is overstating the ease with which that savings can be achieved,” said Rep. Adam Smith, the cerebral and snarky ranking member of the House Armed Services Committee. “But I certainly think the reporting on the report is overstating the ease with which we can save that $125 billion.”

First, divide by five: A crucial detail the headlines always omitted is that the DBB forecast $125 billion in savings over five years. That makes the annual savings from their proposed efficiencies a still respectable but hardly game-changing $25 billion a year. “That’s [about] 4% of total DoD outlays,” calculates Capital Alpha analyst Byron Callan, “which is well within the types of savings corporations would strive to achieve.”

Why does that figure happen to be well within the norm for private sector cost-cutting practices? It’s because the whole premise of the study, in essence, is to ask how much DoD could save if it followed — all together now — private sector cost-cutting practices.

In fact, the analytical underpinnings of the study seem to have been done by McKinsey & Company, a world-famous private-sector management consultancy. McKinsey has a reputation for hiring bright young things with zero experience, a former director convicted of insider trading, and a client roster that includes Enron, AOL before its disastrous merger with Times-Warner, and many more imploded companies. But, whether following McKinsey & Co.’s advice is wise or otherwise, the study’s 77 pages of publicly released briefing slides don’t say how to apply these private-sector practices to the Pentagon — which rather begs the point.

Defense Business Board Study From Jan 2015 by BreakingDefense on Scribd

For example, it says that a “4-8% annual productivity gain for DoD is a realistic goal,” but its only argument for why that’s realistic seems to be that corporations routinely achieve it (slide 9), without saying how well that would translate into the public sector. The study projects “15-40% gains in IT productivity and effectiveness” (slide 19), but it doesn’t say how to realize them, or how hard it might be. To the contrary, the IT goal glosses over the disastrous record of past government information technology mega-projects, even though some of them are cited as case studies in backup slides (49-54). “Even in the private sector, only 17% of fundamental change projects deliver their full potential,” the report admits at one point (slide 26).

Another major area of savings is large-scale early retirements (17-18, 41). While it makes some provision for retention bonuses to keep the most skilled employees (3), the study ignores the looming demographic crisis of too many retirement-age employees leaving the civil service at once, with too few experienced mid-career personnel to replace their institutional knowledge.

“The report lacked specific, actionable recommendations,” Pentagon spokesman Gordon Trowbridge told me. “Where the study did offer concrete recommendations, the department has taken action. For example, we have implemented service contract review boards that are projected to achieve billions of dollars in savings.” Overall, the department is aiming to save $30 billion over four years from efficiencies, an average of $7.5 billion a year.

Andrew Hunter

That’s hardy $25 billion a year, though. “I think it is probably not a reasonable goal, and the work the DBB did doesn’t provide any basis to set it as a goal,” said Andrew Hunter. As the former head of the Pentagon’s celebrated Joint Rapid Acquisition Cell, and now director of defense industrial initiatives at the Center for Strategic & International Studies, Hunter knows a thing or two about making defense procurement faster and more efficient.

Where the DBB does provide specific courses of action, they’re not necessarily feasible, either. “Their proposal to renegotiate contracts across the board is impractical,” Hunter told me, “and they don’t appear to have been aware of the significant efforts (already) underway across the services to reduce service contract costs.”

That said, Hunter emphasizes, “they did a nice job of collecting business operations costs across the Department. The value in what the DBB did is if you collect this information consistently over time, you can detect and act on positive and negative trends in business operations.”

Data is vital to accurate analysis, and the Washington Post‘s most damning accusation the Pentagon “imposed secrecy restrictions on the data making up the study, which ensured no one could replicate the findings.” When I asked Pentagon sources about this, though, they weren’t quite sure what the Post meant.

The substantive section of the report — the 77 slides of recommendations and analysis — “has been available continuously online since January 2015,” said Trowbridge. “We understand some members of Congress might be interested in seeing the underlying data, and, as always, we’ll respond to those requests.”

“Data wasn’t classified, but some was marked proprietary,” said another defense official. “If someone wants the info, they just need to ask and DBB will give it out, minus proprietary stuff.” Proprietary in Pentagon parlance specifically refers to the intellectual property of contractors, and one of the major thrusts of the report was negotiating lower contract costs.

“The report was valuable and continues to shape the way the Department is pursuing efficiencies in cross-enterprise business functions,” the official emphasized. But it’s not an executable plan of action on its own, the official continued, and the Pentagon now “has DBB looking at ways to actually achieve the $125B in savings.”

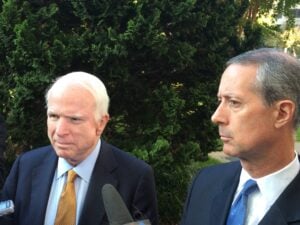

Sen. John McCain and Rep Mac Thornberry, chairmen of the Senate and House Armed Services Committees

The Washington Post story has certainly turned up the pressure to save. The chairman of the House and Senate Armed Services Committees, acquisition reform crusaders Rep. Mac Thornberry and Sen. John McCain, called for all the underlying data to be made public. Their scathing joint statement read (in part), “We have known for many years that the Department’s business practices are archaic and wasteful, and its inability to pass a clean audit is a longstanding travesty. The reason these problems persist is simple: a failure of leadership and a lack of accountability.”

But maybe the reason is not so simple. Maybe it’s a complex interaction of a $496 billion-a-year organization — that’s more than Wal-Mart, the world’s largest company — building cutting-edge hardware and operating it in life-or-death circumstances, all under unrelenting scrutiny from 535 members of Congress.

“It’s an enormously important report, and I think it’s something we should look at closely,” said Rep. Smith, speaking to the US Naval Institute’s annual defense conference at the Newseum. “(But) I wouldn’t get overexcited about it — like, ‘wow, $125 million just laid on the table that we can go spend!'”

“I have not yet encountered the human endeavor that does not contain waste, fraud, and abuse,” Smith said. “There’s waste fraud and abuse at IBM, at Microsoft, at Amazon.” (We just don’t know as much about it because Congress can’t routinely see their books or haul their executives up to testimony). “I think it’s our job in Congress and the job of whoever ends up running DoD to do their level best to get as much of that savings as possible, and I’d be interested in looking at the details of where they think they’re going to get that $125 billion.”

“But,” Smith concluded, “understand it’s not as easy as it might appear.”

Subscribe to our newsletter

Promotions, new products and sales. Directly to your inbox.